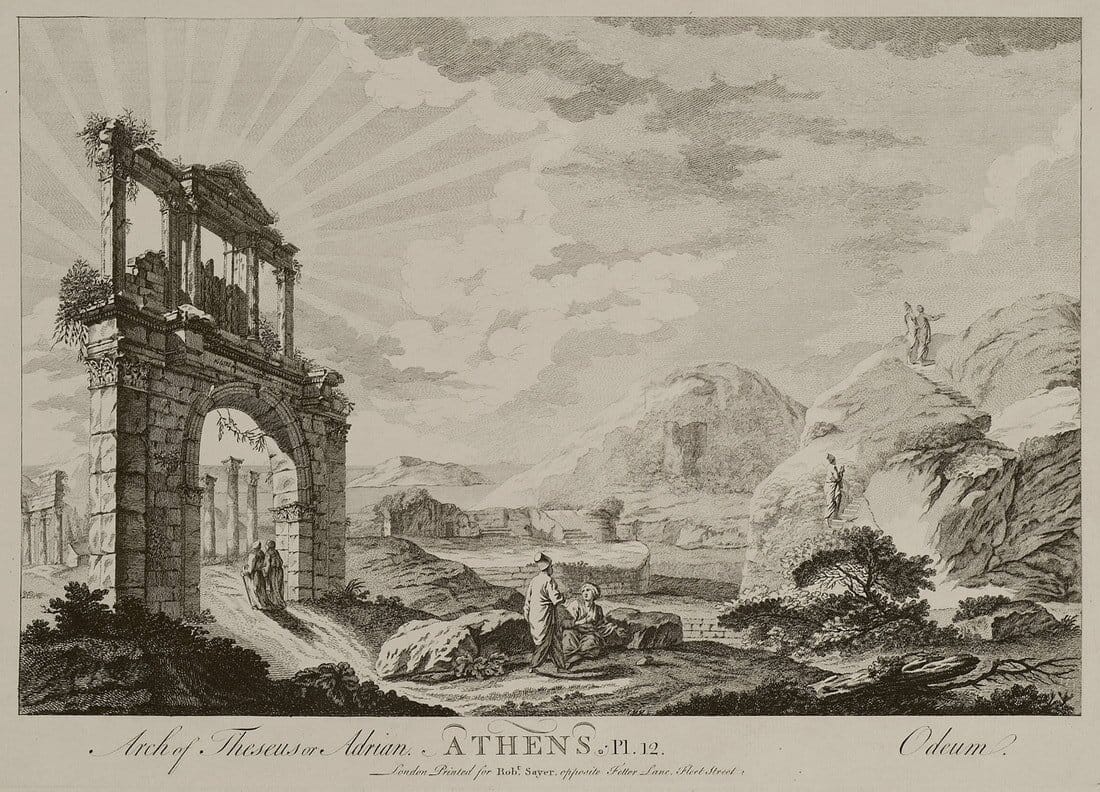

Hadrian’s Gate in downtown Athens, below Acropolis; a Gateway to History

The Arch of Hadrian (Greek: Αψίδα του Αδριανού) commonly referred to as Hadrian's Gate in Greek, is a monumental gateway that bears some resemblance to a Roman triumphal arch.

Hadrian's Gate symbolized the division between the ancient city of Athens and the new Roman city built by Hadrian. It marked the boundary between the old city, which was associated with Theseus, the mythical king and founder of Athens, and the new city areas expanded and developed under Hadrian's rule.

The arch was built in honor of the Roman Emperor Hadrian, who visited Athens in 131 or 132 AD. It was erected to celebrate Hadrian's contributions to the city, particularly his extensive building projects and patronage of Greek culture.

Who was Hadrian? (Publius Aelius Hadrianus)

It is generally accepted that Hadrian was born in Italica, near modern-day Seville in Spain, in 76 AD. His birth name was Publius Aelius Hadrianus. His father, Publius Aelius Hadrianus Afer, was a wealthy and well-known senator, and his mother, Domitia Paulina, came from a prosperous Spanish family. Hadrian's parents died when he was just 10 years old and he was placed under the protection of his father's cousin, Marcus Ulpius Traianus, the one we all know as Emperor Trajan, famous for the Trajan Markets.

Adhering to the typical path of an aristocratic upbringing, Hadrian received an excellent education and he also advanced in the cursus honorum (the sequential order of public offices held by aspiring politicians in the Roman Republic and the early Roman Empire. It was designed for men of senatorial rank). During this time, he developed a deep love for Greek culture.

Serving as emperor from 117 to 138 CE, Hadrian relished his power and used it to extensively reform the Roman Empire. Despite his supreme worldly authority, the divine realm remained above him. Although Roman emperors traditionally achieved deified status posthumously, leaders like Hadrian had to maintain a clear distinction between their mortal rule and full divinity to avoid associations with monarchy—a challenge given Hadrian’s Hellenistic fascinations.

Fortunately, Hadrian found an ideal outlet for his Hellenistic and divine ambitions in Athens. Through his extensive building projects across the empire, Hadrian emulated the grandeur of the Hellenistic leaders he admired. In Athens, in particular, his building programs enabled him to pursue his divine self-styling while also extending and solidifying Roman influence. Specifically, Hadrian’s divine aspirations and desire for supremacy led him to renovate Athens, promote his own ruler cult, and strengthen the Roman Empire as a whole.

Hadrian's journey to becoming emperor followed a relatively standard trajectory. He served three terms as a military tribune—a notable officer rank in the Roman Army—with Legio II Adiutrix, Legio V Macedonica, and Legio XXII Primigenia. This was unusual since most future high-ranking officials typically served only once or twice.

In 101 AD, after Trajan became emperor, Hadrian was appointed quaestor at the young age of twenty-five, a prestigious position that involved acting as a liaison between the emperor and the Senate. He accompanied Trajan during the first Dacian War and later held the roles of praetor and consul in Lower Pannonia, an area that includes parts of modern-day Hungary, Serbia, and Croatia.

Following his service in various military and civil capacities, Hadrian spent some time in Athens before joining Trajan's Parthian campaign in 115 AD. Although the campaign started successfully, it faced numerous setbacks and rebellions, leading to a Roman withdrawal. Trajan died in 117 AD while returning to Rome, and Hadrian was announced as his chosen successor, assuming the title Caesar Traianus Hadrianus.

Hadrian and Greece

While he was emperor, Hadrian did not lose his interest in all things Greek. He was travelling often to Athens and he was “touring” Greece, with the exhortations of the nobles of the time and especially Herod of Atticus.

Herod, was the most celebrated of the orators and writers of the Second Sophistic, a movement that revitalized the teaching and practice of rhetoric in Greece in the 2nd century CE. Born into an immensely wealthy Athenian family that had received Roman citizenship during the reign of the emperor Claudius (41–54). He was befriended by Hadrian, who employed him as a commissioner in charge of eliminating corruption in the free cities of the province of Asia.

Few monuments in Athens are as iconic as Hadrian’s Arch, located on Vasilissis Amalias Avenue in the heart of the city. Known locally as Η Πύλη του Αδριανού, or less frequently, Η Αψίδα του Αδριανού, it may not seem as imposing at first glance compared to other ancient monuments in Athens, especially when juxtaposed with the nearby magnificent ruins of the Temple of Olympian Zeus.

Due to its central location, it is perhaps the most accessible ancient monument in the Greek capital and one of the few that can be visited free of charge at any time of day. The 2nd century CE landmark is not a traditional Roman triumphal arch but an honorary one dedicated to Emperor Hadrian by the citizens of Athens.

Of particular importance are the two inscriptions engraved on the architrave above the apsidal opening on either side of the arch. The west side, facing the Acropolis, proclaims, "ΑΙΔ’ ΕΙΣΙΝ ΑΘΗΝΑΙ ΘΗΣΕΩΣ Η ΠΡΙΝ ΠΟΛΙΣ" (This is Athens, the former city of Theseus). The east side, facing the Temple of Olympian Zeus, declares, "ΑΙΔ’ ΕΙΣ’ ΑΔΡΙΑΝΟΥ ΚΟΥΧΙ ΘΗΣΕΩΣ ΠΟΛΙΣ" (This is the city of Hadrian and not of Theseus). Interestingly, a small slip of the tongue altering a single letter in the monument's official name, Η Πύλη του Αδριανού, transforms it into Η Πόλη του Αδριανού (the city of Hadrian), echoing the message of the latter inscription.

Today, Hadrian is renowned as a philhellenic emperor both in Greece and globally. However, scholars often miss the crucial detail that he was an Athenian citizen and eponymous archon before becoming emperor in 117 AD. He was granted citizenship around 111 AD (or perhaps earlier) and was enrolled in the southern Attic deme of Besa.

Even after becoming emperor, he retained his Athenian citizenship. Consequently, his Athenian identity shaped many of his imperial policies, including his building projects. By the time the arch was dedicated, Hadrian had been an Athenian citizen for two decades.

This raises an important question regarding the arch's inscriptions: were the Athenians honoring him as a fellow Athenian, a Roman, or both?

Photo credits: Scaliger, Getty Images by Canva

The west inscription only includes his Greek cognomen (ΑΔΡΙΑΝΟΥ) without his praenomen, nomen, and titles, suggesting the dedicators were mainly honoring him as their own citizen and benefactor, rather than solely as the Roman emperor.

The arch's placement and the inscription above the apsidal opening, directly facing the Acropolis, were likely chosen deliberately to connect Hadrian to two of Athens' most significant sites. Pausanias noted a statue of Hadrian next to Athena's inside the Parthenon, an extraordinary honor for a mortal, indicating the Athenians' deep respect for him and his close association with the goddess, whom he adopted as a patron deity.

Additionally, the ancient road leading to the arch from the west (modern Lysicratous Street) is believed to have been the location of the prytaneion, said to have been founded by Theseus and served as the official residence of the Athenian archons. This building would have been clearly visible from the eastern side of the archway, the side mentioning the emperor.

Thus, considering the arch's location and inscriptions within the broader monumental context and Hadrian's citizenship status, it is evident that the Athenians regarded him as a new founder of Athens, honoring him primarily as an Athenian who was also the Roman emperor. ("The City of Hadrian and not of Theseus": A Cultural History of Hadrian's Arch by Anna Kouremenos, Western Connecticut State University | WestConn · Philosophy and Humanistic Studies. DPhil in Archaeology University of Oxford)

The arch, made entirely of Pentelic marble, stands 18 meters high, 13.5 meters wide, and 2.3 meters deep. Its design is unique among surviving Roman arches due to its two distinct sections: a lower part resembling a typical Roman triumphal arch and an upper part, known as the attic, divided into three sections with the central one shaped like an aedicula.

The columns feature Corinthian capitals, a common style for Roman arches throughout the Empire. The marble used appears to be of lower quality with many inclusions, suggesting that there might have been a rush to complete the monument before Hadrian’s arrival around 131 AD.

The architect remains unknown, but the arch's location suggests he was likely an Athenian or a resident alien. Initially, the attic was likely decorated with paintings or painted reliefs depicting Theseus and Hadrian, and the possibility of statues or a combination of statues and reliefs is supported by comparisons with the attics of two arches at Eleusis.

Older illustrations depict the inscriptions above the apsidal opening as darker due to weathering and pollution, implying that the letters were probably originally painted in a dark color or gilded with metal, possibly bronze, similar to Hadrian’s Gate in Antalya. Traces of orange-brown paint on the attic suggest that part of it was painted red ochre, a color symbolizing victory and fortitude in antiquity.

It remains unclear whether these paint remnants reflect the original Hadrianic-period color scheme or later repainting during the Byzantine period. The monument, situated on one of the busiest avenues in the city, has accumulated significant pollution and has been cleaned and restored multiple times.

The exact date of the arch’s dedication is unknown due to a lack of ancient references. Its location near the Temple of Olympian Zeus and the association of Hadrian with Theseus in the second inscription suggest it was likely constructed before the later months of 131 AD, when Hadrian arrived in Athens to inaugurate the Temple of Olympian Zeus and the Panhellenion.

Honorary arches were typically constructed during an emperor's reign and rarely posthumously, as evidenced by two other surviving arches dedicated to Hadrian in Antalya and Jerash, which seem to be contemporaneous with the one in Athens. The suggestion that Hadrian commissioned the arch himself is dismissed, as his biographer in the Historia Augusta states that, with one exception, he did not inscribe his name on the monuments he built.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: