Gallienus: The Emperor who Reformed Rome amid Ruin

Gallienus ruled amid collapse—but rather than retreat, he reformed. Misjudged for centuries, he emerges today as a bold strategist and visionary who reshaped Rome’s military and defied the Senate’s grip on power.

He ruled in an age when the empire bled from every border. Goths crossed the Danube, Persians stormed the East, generals declared themselves emperors, and even his own father vanished into captivity. And yet, amid the fire and fragmentation of the third century, Gallienus stood firm—not just as a soldier, but as a thinker.

Dismissed by later ancient sources as effeminate or aloof, modern historians are finally beginning to see him for what he was: a bold reformer, a patron of philosophy, and perhaps the only man who could have held a crumbling empire together for as long as he did.

A Noble Beginning in an Unstable World

Gallienus was born in 218 CE into a distinguished Roman senatorial family at a time of looming imperial unrest. His lineage was patrician on both sides. His father, Valerian, came from the Licinii—a plebeian family of Etruscan origin that had risen to prominence in Rome’s senatorial ranks—while his mother, Egnatia Mariniana, belonged to the equally influential Egnatii.

Though some later questioned the purity of these familial ties due to the common use of names among freedmen, contemporary sources leave little doubt that Gallienus was born into Rome’s aristocratic elite. His later admiration for Plotinus and Greek philosophical thought hints at a deep engagement with intellectual life, possibly even including study in Athens.

His childhood likely unfolded in the town of Falerii Novi, a stronghold of his maternal and paternal families, situated along the Via Egnatia near Rome. Though we know little about his early years, Gallienus would have received the full breadth of a noble Roman education—Greek and Latin grammar, rhetoric, philosophy, and law—followed by military training that prepared him for command.

His wife, Cornelia Salonina, belonged to the ancient gens Cornelia and was of equally noble standing. The marriage, like many among Rome’s ruling elite, was likely political in origin—but evidence suggests it also became a genuine partnership. Their children—Saloninus, Valerian II, and Marinianus—were all born in the years leading up to Gallienus’s accession and were still very young when raised to the rank of Caesar.

Before he ruled, Gallienus likely served in military campaigns and provincial postings, perhaps alongside his father Valerian. His career would have followed the senatorial cursus honorum—though by the mid-third century, this traditional ladder of offices was beginning to fracture. Still, his military experience and noble lineage made him a natural choice when Valerian ascended to the purple in 253 and named his son co-emperor.

What followed was one of the most turbulent periods in Roman history—and Gallienus would be forced to lead not from the comfort of inheritance, but from the heart of crisis.

Portrait bust of Emperor Gallienus. Credits: Jamie Heath, CC BY-SA 2.0

Before the Storm: The Road to Power for Gallienus and Valerian

In the years leading up to Gallienus’s accession, the Roman Empire endured a cascade of crises: military defeats, political betrayals, religious persecution, and devastating invasions.

The ultraconservative Emperor Decius, seeking to restore Rome’s ancient values, launched a brutal campaign against Christians and centralized power through aggressive religious policy. But his efforts unraveled when Gothic tribes, led by Kniva, invaded the Balkans. Decius’s catastrophic military decisions culminated in his death at Abrittus in 251, leaving the empire vulnerable.

His successor, Trebonianus Gallus, initially sought stability by adopting Decius’s son and continuing his policies but quickly lost public support through appeasement of the Goths and a failure to contain a deadly plague.

In the East, Persian forces under Shapur I overran key cities, aided by local collaborators like the traitorous Myriades. Meanwhile, internal power struggles erupted as Aemilianus, a general in the Balkans, defeated Gothic raiders and declared himself emperor.

As Gallus faltered, Valerian, a powerful senator and military commander, emerged as a contender for the throne. Backed by his son Gallienus and Senate allies, Valerian was ultimately declared emperor after both Gallus and Aemilianus were eliminated in rapid succession.

With the empire fractured and under siege, Valerian and Gallienus would assume joint rule in 253—a bold experiment in dual leadership born out of necessity and upheaval.

Triumphal Arch of Gallienus, built after his time. Credits: PippaWest from Getty Images, by Canva

A Divided Rule and Immediate Crisis

As Gallienus was elevated to co-emperor alongside his father, Valerian, he was tasked with securing the Western Empire while Valerian moved East. Their reign began during a time of profound instability—marked by invasions, economic disruption, and internal fragmentation.

Valerian’s ultraconservative stance brought the senatorial class back into influence, evidenced by his harsh persecution of Christians in 257, possibly under the influence of his court magician Macrianus.

A Collapsing Economy and Rural Shift

Ongoing military catastrophes and plagues devastated the Empire’s agricultural and economic foundations. Small landholders sought refuge under powerful landowners to escape increasing taxation, eroding the urban tax base and shifting productivity to villa-based estates.

Simultaneously, the Roman coinage was debased to such a degree that silver coins lost their value in international trade. This led to a collapse of confidence in currency, growing inflation, and a breakdown in traditional commerce and industry.

Gallienus’s Monetary Policies and Struggles

Facing revolts, foreign invasions, and diminished revenues, Gallienus resorted to issuing debased coinage at an unprecedented scale to fund the military.

Although initially inflation spurred some economic activity, by the 260s, chaos in monetary standards led to a loss of public trust and widespread hoarding of quality coinage. Emergency measures included confiscating wealth, imposing special taxes, and levying soldiers from aristocratic estates—all of which deepened elite resentment.

Propaganda and Coinage

Gallienus used coins not only to fund the army but also as a tool of imperial propaganda. His coinage emphasized military loyalty, heroic imagery, and divine favor—employing slogans like Fides Militum, Victoria Augusti, and Virtus Augusti.

He also experimented with representations of civilian peace and Greek-inspired motifs, including coins featuring Sol, and possibly his own image in feminine form—a controversial move later interpreted as philosophical or symbolic.

Credits: Portable Antiquities Scheme, CC BY-ND 2.0

Military Innovation: The New Army

A major legacy of Gallienus was the creation of a powerful, mobile cavalry corps and accompanying infantry comitatus. These forces included specialized units like the Equites Dalmatae, Moorish javelin throwers, and archers from Palmyra and Osrhoene.

Command was entrusted to officers like Aureolus, and Gallienus is believed to have reintroduced the role of Magister Equitum. This military restructuring reflected Gallienus’s priority: maintaining loyalty and striking quickly in response to crises.

The Role of the Protectores and Internal Security

Gallienus expanded the bodyguard corps known as Protectores Domestici, possibly integrating intelligence, military training, and imperial security into a unified institution. These protectores not only served as elite guards but may have acted as political monitors and recruiters, forming a loyal core around the emperor during a time of constant internal threat.

Organizational Reform and Tactical Structure

Sources suggest Gallienus’s army was divided into heavy shield-bearing cohorts and diverse light-armed units, supported by tactical deployments of cavalry. This structured and specialized military approach—potentially recorded by sixth-century author John Lydus—points to Gallienus’s broader attempt to modernize the imperial defense network in response to repeated emergencies.

Gallienus Alone: Crisis, Reform, and Survival in the Mid-Third Century

Gallienus’s sole reign began under dire circumstances in 259 CE, following the catastrophic capture of his father, Emperor Valerian, by the Persians. Simultaneously, barbarian invasions and internal revolts erupted across the empire.

The Roman frontiers were under attack from the Alamanni, Iuthungi, and Franks, while generals and administrators questioned Gallienus’s legitimacy and leadership, partly due to his perceived negligence toward his father and his personal habits, which clashed with the military conservatism of the time.

One of Gallienus’s earliest challenges was the massive invasion of Italy by the Alamanni and Iuthungi, who pushed deep into the peninsula, forcing the Senate to organize a temporary defense of Rome.

Gallienus responded decisively, defeating the Alamanni near Milan in a brilliant cavalry maneuver around 260 CE.

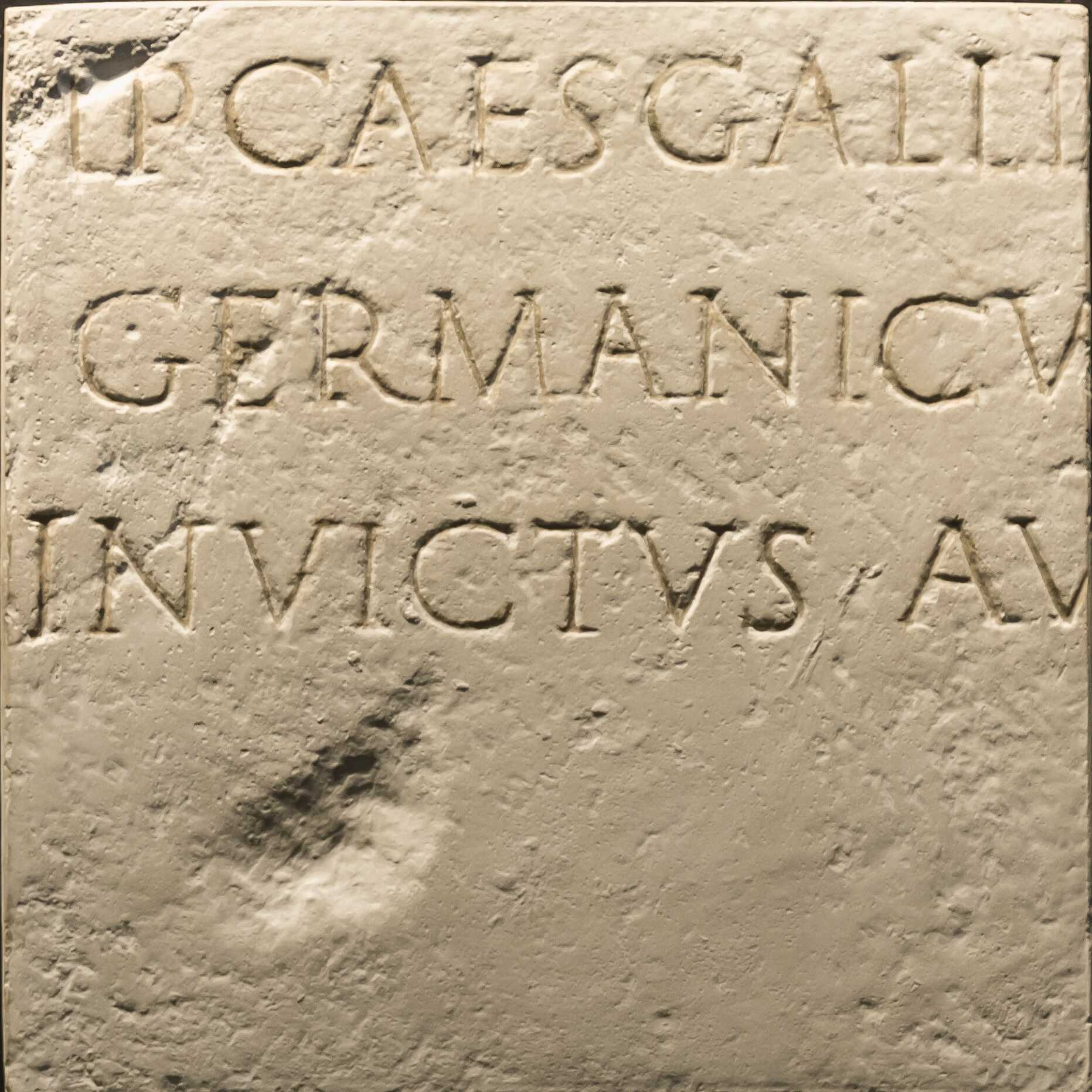

Cast of the inscription of the Roman emperor Gallienus concerning the wins of the Romans against the Alamans. Credits: Raimond Spekking, CC BY-SA 4.0

The Iuthungi were later repelled in Raetia. These campaigns demonstrated Gallienus’s growing reliance on his mobile cavalry force, which he developed into an elite, mobile central reserve army. Estimates suggest this cavalry force reached between 10,000 and 45,000 horsemen and included diverse elements from across the empire, from Moorish javelin throwers to Sarmatian archers.

Facing widespread internal instability, Gallienus implemented sweeping military and administrative reforms. Most notably, he excluded senators from senior military commands, ending their traditional role as legionary commanders.

He appointed experienced equestrian officers instead, many from the Balkans or drawn from his bodyguard units, the protectores. Gallienus also began replacing provincial governors with military officials holding temporary unified civil and military authority in critical regions.

Though not universally applied, these changes effectively centralized power and increased efficiency—but alienated the Senate, earning Gallienus their lasting hostility. In tandem, Gallienus reversed his father's persecution of Christians, ending the anti-Christian edicts of 257 and 258 and adopting a policy of tolerance. This move had practical military benefits, encouraging Christian support within the army.

The Christian historian Orosius later claimed divine retribution struck those who had previously persecuted the faithful. Whether symbolic or administrative, the shift helped stabilize internal support and undermined the ideological justification for rebellion by conservative elites.

Economically, Gallienus's reign saw continued crisis. Ongoing wars, plague, and inflation weakened the empire’s tax base. In response, he debased the silver coinage to historically low levels and increasingly paid troops in kind (annona) rather than currency.

He also confiscated elite property—sometimes on dubious grounds—and converted it into imperial estates to fund the army. This alienated the wealthy but secured emergency resources. Despite accusations of monetary chaos, these measures temporarily stabilized military funding and allowed Gallienus to continue governing amid collapse.

To maintain morale and authority, Gallienus continued using coinage as a vital propaganda tool. He issued vast numbers of coins extolling military virtues and victories, referencing Fides Militum, Virtus, and Victoria, and depicting deities such as Mars, Jupiter, Sol, and Hercules.

His propaganda emphasized divine favor and heroic leadership, portraying him in godlike form and highlighting loyalty from the army. Even eccentric coin types, such as the feminized “Galliena” portrait series, may have expressed his cultural philhellenism or allegorical aspirations—though they also invited mockery and suspicion.

Credits: Kent 1978

Overall, Gallienus’s sole rule was marked by unrelenting crises—foreign invasions, economic disintegration, Senate opposition, and religious tensions—but also by adaptive reforms, military innovations, and strong control over propaganda. His capacity to maintain imperial unity and security through institutional and strategic creativity ensured the empire’s survival during one of its most precarious decades. (The Reign of Emperor Gallienus-The Apogee of Roman Cavalry, by Dr. Ilkka Syvanne)

Reclaiming Gallienus: A Misunderstood Emperor

Far from being the decadent and effeminate figure mocked by later Latin historians, Gallienus emerges in a different light when freed from the distortions of senatorial hostility. During a time of unrelenting crisis, when the Roman world seemed to be crumbling on every front, Gallienus attempted to impose stability through reform rather than reaction.

He reshaped the military command structure, placing power in the hands of career officers rather than aristocratic amateurs, and nurtured a philosophical worldview shaped by Neoplatonism and Greek traditions. His tolerance toward Christians, his efforts to decentralize the army, and his embrace of a new kind of imperial ideology all point to a ruler who was forward-thinking, not feeble.

Yet the price of alienating the traditional elite was high. Latin historians, often themselves products of the senatorial class, repaid Gallienus’ marginalization of their peers with a campaign of memory against him — one that turned a pragmatic reformer into a figure of ridicule. In the end, it is not Gallienus who failed the empire, but history that failed Gallienus. (Gallienus: A Study in Reformist Leadership and Suppressed Memory, by Troy Kendrick)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: