Foundations of Justice: Rome’s Twelve Tables

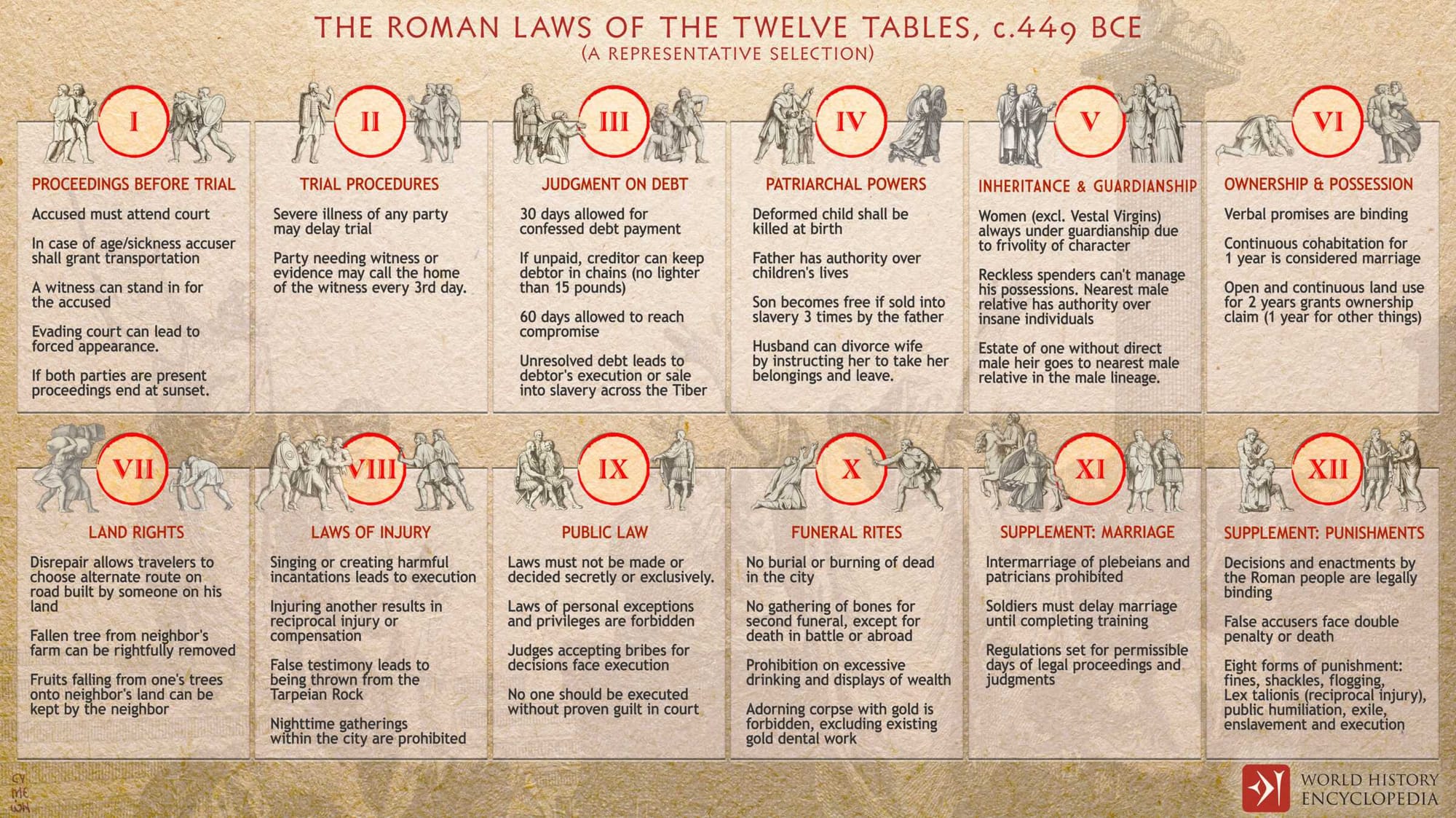

Traditions or laws? Lex duodecim tabularum was the legislation that stood at the foundation of Roman law.

Beneath the towering monuments of ancient Rome lies the faint echo of a groundbreaking legal code, the Twelve Tables—a collection of laws. But what were these enigmatic statutes, etched on bronze for all to see? Who decided what was just or unjust in a city bursting with ambition and conflict?

The Twelve Tables were more than laws—they were a declaration of Rome’s identity, an attempt to codify order in the face of chaos. And yet, so much about them remains shrouded in mystery. Why were they created, and what secrets do they hold about life, justice, and power in ancient Rome? To decipher the Twelve Tables is to glimpse the very soul of the Roman Republic.

Tarquinius Superbus, the final king of ancient Rome, was known for his ruthless nature, as Livy described: “brutality was his nature.” Following his exile in 510 BC, Rome entered a new era characterized by – as Livy again writes — “the history in peace and war of a free nation, governed by annually elected officers of state and subject not to the caprice of individual men, but to the overriding authority of law.”

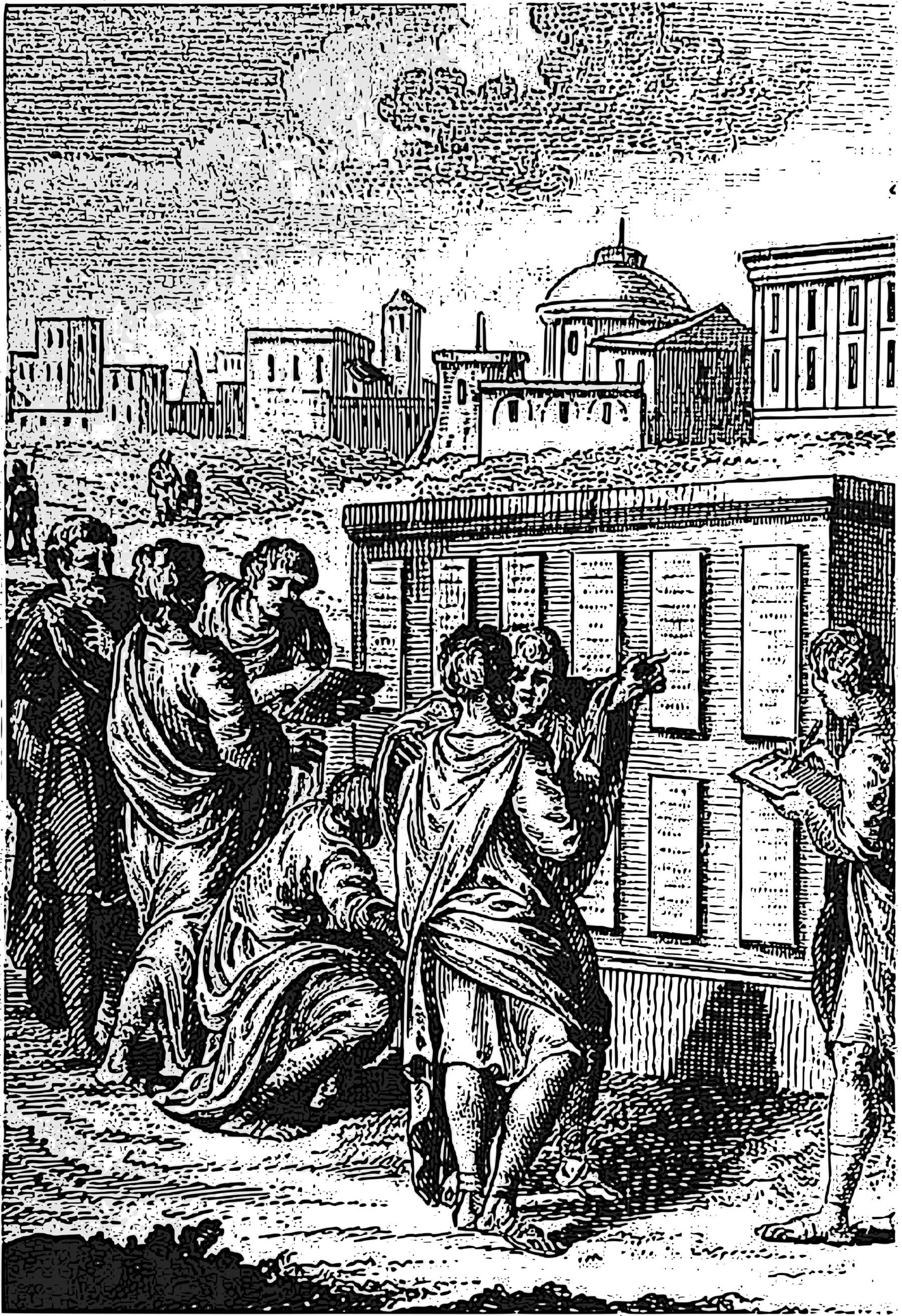

Around 450 BC, a significant milestone in Roman legal history occurred with the creation of the Twelve Tables—a collection of laws which Livy describes as “engraved on bronze and permanently exhibited in a place where all could read them.” (The Twelve Tables, by Samuli Hurri)

The Twelve Tables and the Quest for Equality

The Twelve Tables represent the earliest codified laws of Rome and the cornerstone of its legal tradition, described by Livy as the fons omnis publici privatique iuris, or "the source of all public and private law." During the first half of the fifth century B.C., the struggle for equality between the patricians and the plebeians reached its height.

The plebeians steadily gained recognition of their civil rights and access to government roles, reducing the oppressive dominance of the patrician class. Complaints from the plebeians about their subjugation under patrician-controlled legal and governmental powers spurred the creation of the Twelve Tables. These laws served to establish clear rights and penalties, safeguarding the plebeians from being exploited under the guise of legal authority.

In 451 B.C., a group of ten officials known as the Decemvirs, all from the patrician class, was appointed to draft a set of laws. During this time, they were granted complete control over the government to focus on their task. The resulting Ten Tables were approved by the Roman populace and displayed in the Forum on bronze or copper plaques.

TABLE III

AERIS CONFESSI REBUSQUE IURE IUDICATIS XXX DIES IUSTI SUNTO.

The following year, in 450 B.C., another group of Decemvirs was appointed, this time consisting of seven patricians and three plebeians, who added two more tables. These became collectively known as the Laws of the Twelve Tables. Unfortunately, the original tablets were destroyed in 390 B.C. during the sack of Rome by the Gauls. However, fragments of the laws and references to over a hundred provisions have survived through the writings of figures such as Cicero, Gaius, and Ulpian.

Although they were not a completely new legislative code, they primarily acted as a formal restatement of earlier laws. While some provisions may show similarities to the Laws of Solon and other Greek influences, they remained fundamentally Roman, incorporating much of Rome’s earlier legal tradition. Despite the destruction of the tablets, the essence of the Twelve Tables was preserved through legal commentary, and many of their provisions were later included in the Code of Justinian. (The Laws of The Twelve Tables, by E.B Conant, assisted by Florence Reingruber)

Echoes of Greece in Rome’s Legal Code: Unpacking the Twelve Tables

The journey of Roman law begins with the Twelve Tables, recognized as the earliest legal framework of the city that can be reconstructed with some certainty. Although some provisions of this code were undeniably harsh, Roman jurists and legal scholars later held them in high regard, appreciating the robust legal system they developed from its concise principles.

While modern scholars are less reverent, they have poured extensive effort into reconstructing and interpreting the code. A compelling reconstruction was achieved in the 16th century, sparking centuries of historical study to uncover insights about Rome’s past and the republican virtues believed to have propelled the city to global dominance.

However, they only survive in fragments, with no partial or complete copies remaining—a perplexing enigma outside the scope of this discussion. A deeper puzzle lies in the Roman historians’ own accounts: despite their pride in their legal tradition, they attributed the Twelve Tables—and, by extension, Roman law—to Greek origins.

According to tradition, the monarchy’s fall in 509 BCE amplified patrician power, even as plebeians secured the tribunate. Yet the patricians’ control over judicial power and the secrecy of laws continued to preserve their dominance. To challenge this, the plebeians demanded a written code that would limit judicial discretion.

After a decade of struggle, the patricians conceded in 451 BCE and sent a delegation to Athens to study Greek laws. Upon their return, a committee of ten officials (the Decemvirs we spoke about) combined Greek legal principles with Roman customs, inscribing them on ten tablets displayed in the Forum. A second Decemvirate later, as already mentioned, added two more tablets, completing the Twelve Tables.

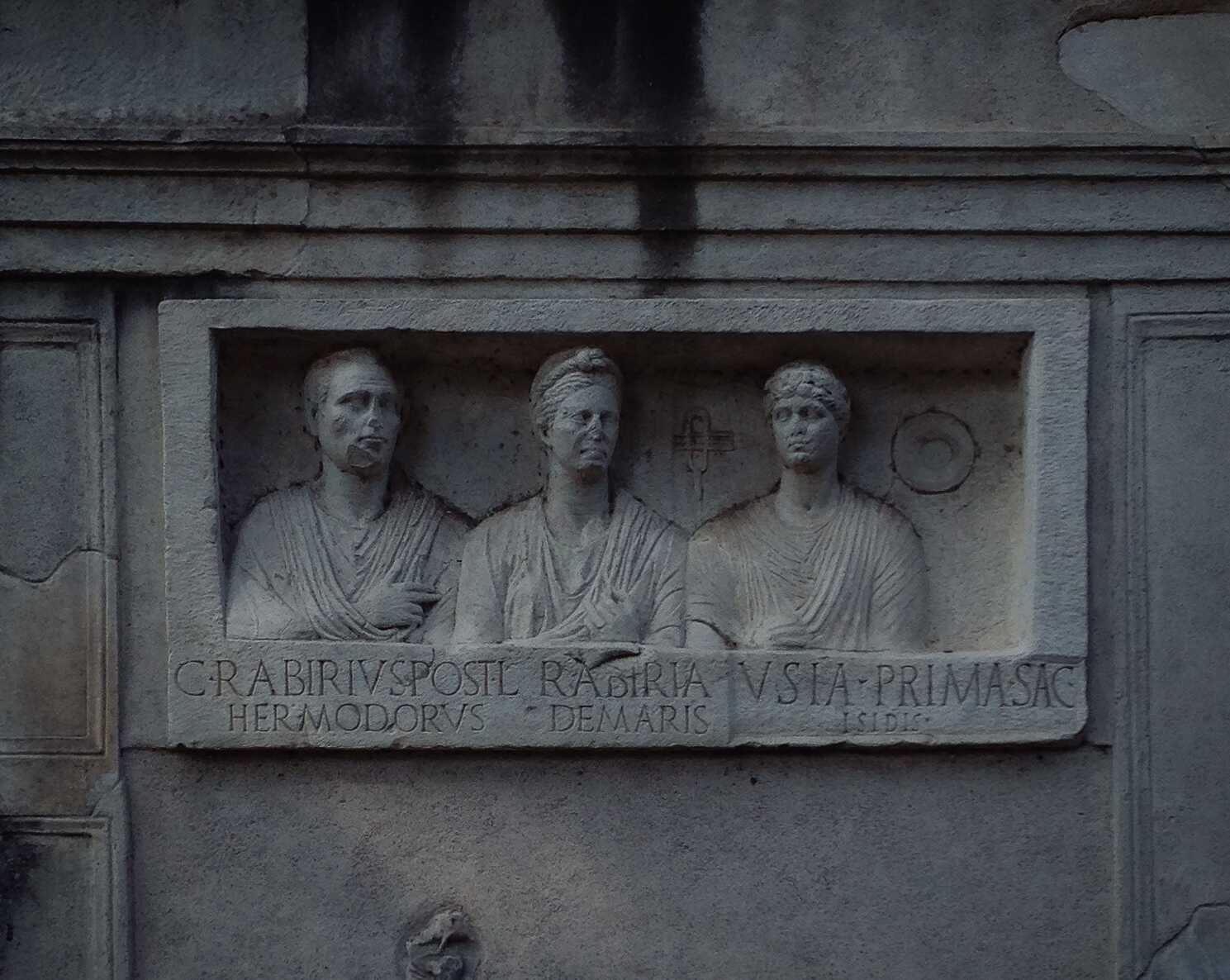

An additional Greek connection comes from the story of Hermodorus, an exiled Ephesian sage who purportedly played a significant role in interpreting the Greek legal elements for the Decemvirs. His contributions were so valued that a statue was erected in his honor in the Forum.

This narrative, preserved by Livy and Dionysius of Halicarnassus, was widely accepted until the 18th century. Giovanni Battista Vico (an Italian philosopher, rhetorician, historian, and jurist during the Italian Enlightenment), in his New Science challenged this story, eventually questioning the existence of the Twelve Tables altogether.

Although Vico’s objections initially had little impact, 19th-century scholars began to doubt Livy’s accuracy, dismissing the notion of significant Greek influence. Historians like Niebuhr and Mommsen concluded that while a Roman delegation might have visited Athens, its impact on the Twelve Tables was negligible.

By the late 18th century, a different debate emerged regarding the origins of the Twelve Tables. French historians Pierre-Nicolas Bonamy and Antoine Terrasson discussed the matter in depth, framing their arguments within broader philosophical views on the origins of human societies. Their exchange offers valuable insights not only into Roman law but also into 18th-century assumptions about humanity and civilization.

Rethinking Roman Law: Vico’s Critique of the Twelve Tables’ Greek Connection

The Twelve Tables, were described by Mommsen as "the first and only legal code of Rome." However, this characterization has been contested by scholars. To modern observers, they seem more like a compilation of various statutes rather than a comprehensive legal code, a view shared by Vico.

Although he rejected the notion of them as a code, he regarded them as vital evidence of early Roman history, describing them as the recorded customs of Latium’s heroic peoples. According to him, these laws were a "serious poem" that encapsulated legal relationships in the form of dramatic fables.

Vico’s rejection of their Greek origins was rooted in his broader historical philosophy.

A painting by Francesco Solimena of Portrait of Giovan Battista - or Giambattista - Vico, the italian philosopher, historian and jurist. Upscaling by Roman Empire Times

He argued that all nations progress through three ages—the age of gods, the age of heroes, and the age of men—each with its own distinct forms of thought and law. The Twelve Tables, he claimed, belonged to the heroic age of Rome, while Athens had already entered the age of civil law. He maintained that the poetic, heroic peoples of Latium could not have comprehended or adopted the rational, philosophical laws of Athens.

In his view, nations develop their laws and institutions internally, shaped by their unique cultural identity, or ingenium. He rejected the idea of significant cultural borrowing in the early stages of a nation’s development. Thus, for him, the Romans could not have adopted Greek laws, as each society’s legal framework was dictated by its stage of development and cultural character.

Initially, he accepted the traditional story of the Roman deputation to Athens, but he later dismissed it as a fabrication, suggesting that the story was a patrician ploy to delay plebeian demands for a written code. He argued that scholars of later, rational ages retroactively interpreted the Twelve Tables through their own philosophical lens, transforming them into a "code" resembling the rational laws of their own time.

Vico drew parallels between this reinterpretation and his critique of Homer. Just as Homer was not a single poet but rather a collective representation of Greek heroic society, the Twelve Tables were not a rational code but a reflection of the natural law of Latium’s heroic gentes. He asserted that the scholarly "conceit" of both Rome and Greece had falsely attributed these laws to Greek influence.

According to his theory, law was a secondary phenomenon, reflecting the broader development of society. He believed that nations’ governments and legal systems must align with the character of their people, as dictated by divine Providence. Thus, he dismissed the story of the deputation and any claims of Greek influence as incompatible with the unique development of Roman society. For Vico, the differences between Roman and Athenian historical trajectories invalidated the notion of a borrowed legal framework. (The Twelve Tables and Their Origins: An Eighteenth-Century Debate, by Michael Steinberg)

Were the Twelve Tables Truly a Roman Legal Code?

The Twelve Tables have traditionally been regarded as a lex—a legislative statute reflecting a codified legal framework and they were perceived as a comprehensive codification of Roman law that emerged from the sociopolitical struggles between patricians and plebeians.

Modern scholarship largely upholds this interpretation, emphasizing them as the product of deliberate intellectual effort by the Decemvirs and confirmed through legislative procedures around the mid-5th century BCE. This perspective highlights their importance as a sweeping reform aimed at addressing plebeian grievances.

However, challenges arise when applying this view to the actual content and form of the Twelve Tables, as reconstructed from surviving fragments.

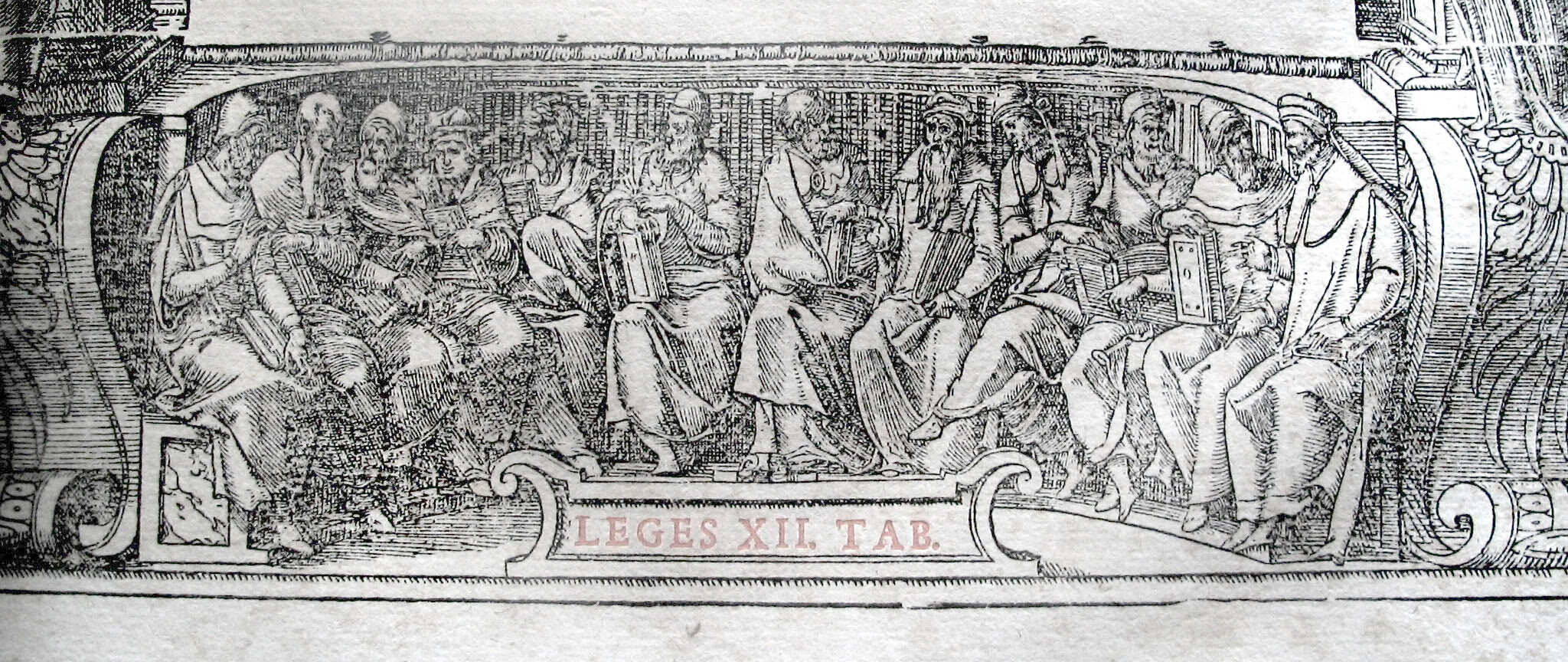

The law of the Twelve Tables engraving by Claude-Nicolas Malapeau. Upscaling by Roman Empire Times

Their text predominantly employs a casuistic style, presenting specific solutions to narrowly defined circumstances: "If a man does X, he shall be subject to Y punishment."

Scholars, such as Daube, have noted that this form differs significantly from the abstract norms and principles characteristic of later Roman legislation. This discrepancy raises questions about whether the sophisticated legislative machinery attributed to the Decemvirs aligns with the simplicity of the society that produced the Twelve Tables.

Wieacker (a German lawyer and legal historian) identified two main stylistic features in the text: laconic imperatives and conditional sentences. Occasionally, rules like Qui malum carmen incantass… (Whoever has chanted an evil spell…) could be reformulated as conditional sentences, underscoring their specific, situational nature rather than broader legal principles. The text’s focus on resolving immediate, narrowly defined issues further challenges the notion of the Twelve Tables as a comprehensive code, even within the scope of private law.

Modern scholars, have suggested that their text alludes to unwritten customary laws that were widely understood at the time, making it unnecessary to state them explicitly. Kaser in turn (a renowned German legal historian and scholar, particularly known for his work on Roman law), argued that the Roman view of the Twelve Tables as comprehensive was a later legal fiction. He posited that while they confirmed or amended certain rules, the majority of Roman law remained rooted in unwritten traditions (mos maiorum).

TABLE V

SI INTESTATO MORITUR, CUI SUUS HERES NEC ESCIT, ADGN A T U S PROXIMUS FAMILIAM HABETO

Their content also complicates the narrative of their historical purpose. Despite their purported aim to address plebeian grievances, the extant text offers little evidence of social reforms favoring the plebeian class. For instance:

- The only explicit reference to social classes is a prohibition on intermarriage between patricians and plebeians, which contradicts the idea of plebeian-friendly reforms.

- The harsh debt rules, such as allowing creditors to bind debtors with heavy fetters, hardly suggest legislation favoring the debtor, often associated with the plebeian class.

- Most of the rules address private law topics like inheritance, procedure, and delict, which could apply universally across societies.

- A small number of rules address religious practices, such as funeral customs, with no apparent social implications.

The simplicity of these provisions undermines the argument that the Twelve Tables were intended to demystify the law for plebeians. Basic rules, such as the prohibition on burying bodies within city limits, would have been evident through enforcement alone. Meanwhile, subtler legal nuances—if hidden from plebeians—are not clarified in the text.

As Watson observed, (a distinguished Scottish legal scholar and historian, renowned for his expertise in Roman law and comparative legal history. His interpretations of Roman law, including his insights on the Twelve Tables, often challenged traditional views, focusing on the social and historical contexts of legal development) “Law remained a mystery,” as the Twelve Tables provided no guidance on critical elements like the forms of action (legis actio).

Connections to Ancient Near Eastern Law?

The classical narrative surrounding the Twelve Tables suggests foreign influence, most notably through the alleged Roman mission to Greece, as already mentioned. However, modern scholars have often favored a nationalistic interpretation.

Westrup for instance (a prominent Danish legal historian, specializing in Roman law and its connections to broader Indo-European legal traditions), confidently stated that they were "essentially of national Roman origin," while acknowledging the possibility of a single precept drawing inspiration from Solon's laws. He argued that the roots of Roman law should be traced to its Indo-European heritage.

Contrasting this view, Müller’s 1903 thesis (a German classical scholar and historian, widely recognized for his work in ancient Greek and Roman studies) proposed a bold connection between the Twelve Tables and Ancient Near Eastern legal traditions. He observed similarities between them, the Covenant Code in Exodus, and the Code of Hammurabi. He suggested a shared Semitic "Urgesetz" (primordial law) that influenced these legal systems through Greece, which the Roman Decemvirs might have encountered.

However, Müller's hypothesis has faced widespread criticism, particularly from scholars like Volterra (a prominent Italian legal historian and jurist, widely regarded as one of the foremost scholars of Roman law in the 20th century.) Volterra, in his detailed analysis, rejected the possibility of any connection between early Roman law and Ancient Near Eastern legal systems. Through comparative studies of institutions, he concluded that these systems were fundamentally incompatible.

He himself however acknowledged that future archaeological discoveries could challenge his findings. Indeed, advancements in cuneiform studies and new material evidence have since rendered much of the earlier scholarship on Ancient Near Eastern law outdated.

His approach, however, reveals a methodological issue. He relied heavily on classical Roman interpretations of early law, which might themselves be distortions. Later Roman jurists and historians, interpreting the Twelve Tables through their own societal frameworks, were unlikely to grasp the original contexts or intentions behind these laws.

As Watson aptly put it, “There is really very little connection between early Roman law and, say, the law of Babylon, but the law of the later Roman Republic and of the classical period is the immediate descendant of the law of the early Republic and the XII Tables.”

Yet, the obscurities and inconsistencies in the Twelve Tables raise questions about this linear interpretation. Many terms were already unclear to Romans in later periods, and subsequent interpretations often reflected contemporary needs rather than historical truths. Moreover, Roman traditions, while preserved, must be scrutinized carefully, as they often imposed later conceptions on earlier laws. (The Nature and Origins of the Twelve Tables, by Raymond Westbrook)

TABLE VIII

MANU FUSTIVE SI OS FREGIT LIBERO, CCC, SI SERVO, CL POENAM SUBITO

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: