Faustina the Younger: From Imperial Daughter to Deified Empress

Faustina the Younger, also known as Annia Galeria Faustina Minor, was a prominent Roman empress in the 2nd century CE.

Who was Faustina the Younger?

Annia Galeria Faustina the Younger was born around 130 CE into a distinguished family. She was the daughter of Roman Emperor Antoninus Pius and Empress Faustina the Elder. She married her maternal cousin, Emperor Marcus Aurelius. She was highly respected by soldiers and her husband, holding the titles Augusta and Mater Castrorum, and received divine honors after her death.

Faustina the Elder and Faustina the Younger, were notable Roman empresses from the affluent Spanish and Narbonensian aristocracy. Both empresses were admired during their husbands' reigns, which marked the height of the Roman Empire in the mid-second century AD. Their appearances are not well-documented, but coins and sculptures suggest they had a dignified and seductive presence, especially Faustina I.

Faustina I had four children, and Faustina II had about 15 with Marcus Aurellius though few survived to adulthood. The empresses wielded significant influence for forty years, with Faustina II enhancing her mother's role and clarifying the public and political position of the emperor's wife.

Faustina and Marcus Aurelius

Emperor Antoninus altered Hadrian’s succession plan by adopting Marcus Aurelius as his heir and arranging his marriage to his daughter, Faustina. Marcus would rule for nineteen years as the last of the “five good emperors,” while Faustina would become the first woman to follow her mother as a Roman empress.

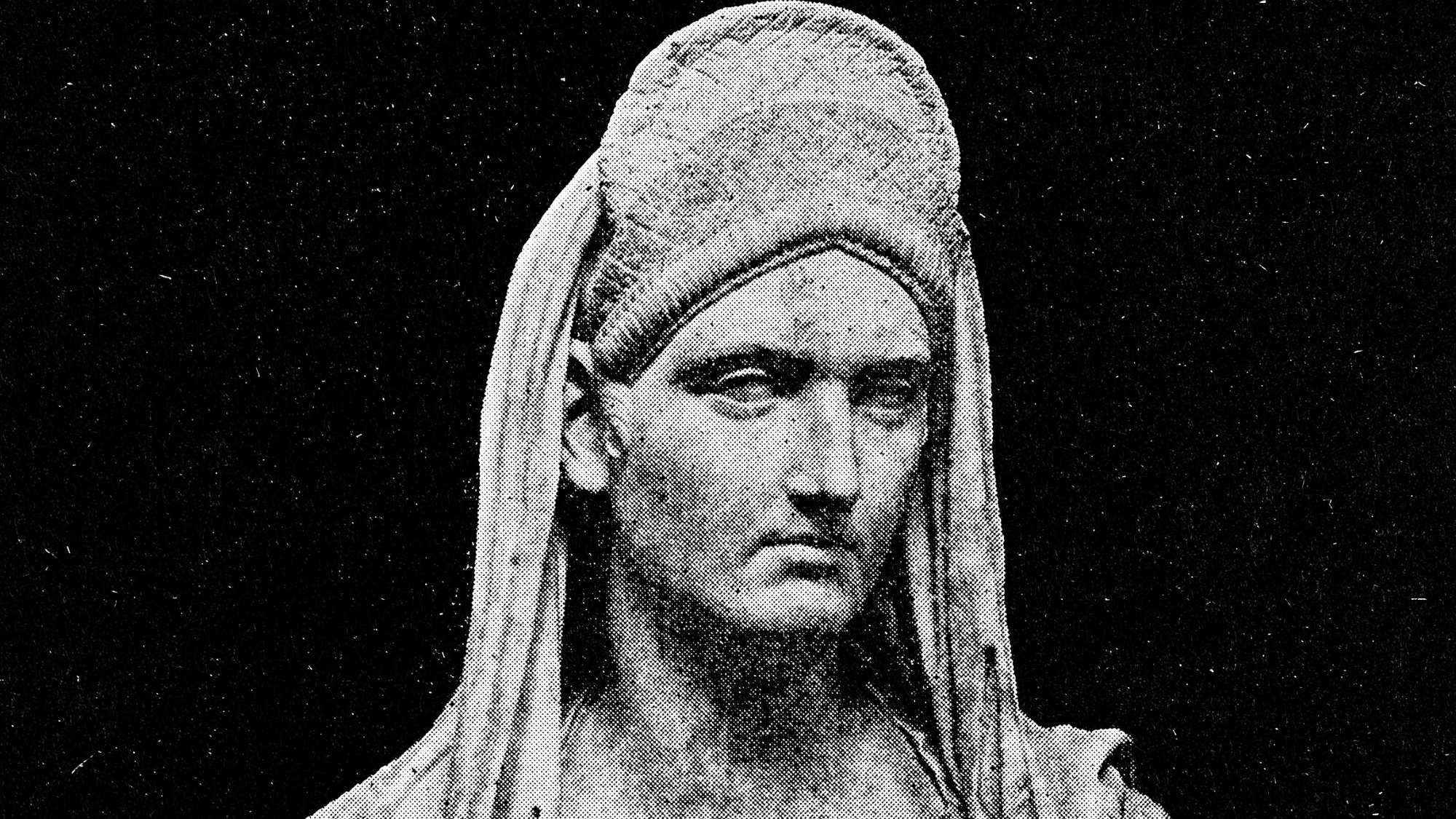

Despite her reputation for promiscuity and disloyalty, Faustina the Younger, born in the early to mid-120s or possibly around 130, is depicted in portraits as a beautiful and cheerful woman, like her mother. She had gentle eyes, a pointed nose, full cheeks, and a small mouth. Her hair, styled in various ways with soft curls or waves and a bun, was so admired that it was imitated by the ladies of Napoleon’s court over 1,600 years later.

As the daughter of an emperor at the height of Roman power, Faustina lived in great splendor. Her father’s dedication to duty was complemented by her mother’s elegance and cheerfulness, creating a bright atmosphere in the palace. Faustina lost her mother during her mid-teens, a very important time in her life. She was pleased when her engagement to the young Lucius Verus was canceled in favor of her betrothal to the noble and attractive Marcus Aurelius.

In the spring of 145, about four years after her mother's death, Faustina and Marcus were married. This event likely generated significant excitement in Rome, marking the most prominent imperial wedding since Nero and Octavia's union nearly a century earlier. Faustina's father, Antoninus, officiated the ceremony, and coins were minted depicting the bride and groom together.

On 30 November 147, Faustina gave birth to her first child, Domitia Faustina, marking the beginning of at least fourteen children she and Marcus Aurelius would have over the next twenty-three years. Following the birth, Faustina received the title of Augusta, and Marcus was granted additional powers.

Although Faustina's fertility brought joy to the imperial family, it also resulted in sorrow, as only six of their children survived to adulthood, with their son Commodus becoming an infamously poor emperor.

Letters between Marcus and his tutor, Marcus Cornelius Fronto, provide insights into the family's daily life, showing their active involvement in their children's upbringing. These letters depict a close-knit family, contrasting with the typical detachment of elite patricians. Faustina's first set of twins, born in 149, were commemorated on coins, highlighting their significance to the family.

Her first twin boys were born in 149. These later twins, one of whom was Commodus, were born on 31 August 161, nearly six months after Antoninus Pius's death and their father's ascension as emperor. Marcus Aurelius set a precedent by appointing the younger Lucius Verus as his co-emperor, granting him equal power in all respects except for the role of chief priest (Pontifex Maximus), which Marcus alone held.

This arrangement, reinstating Hadrian’s original plan, succeeded because Lucius Verus respected and deferred to his older colleague.

Around the year 170, Faustina gave birth to her last child, a girl named Vibia Sabina, after Hadrian's wife. With the end of her childbearing years, Faustina felt free to join her husband at his fortifications on the northern frontier. She and her younger children spent extended periods with him at his headquarters, enduring the relative hardships of life at the front. In 174, Marcus honored Faustina with the unprecedented title Mater Castrorum, or "Mother of the Camp," which was commemorated on coins bearing her image. (Great women of imperial Rome, Mothers and Wives of the Caesars by Jasper Burns)

Rumors about Faustina

In addition to her alleged affairs with gladiators, Faustina is believed to have had relationships with sailors and soldiers. These affairs fueled rumors about her son, Commodus, suggesting he was the offspring of one of Faustina's lovers, possibly making him an 'illegitimate' child.

Although these claims were never confirmed, many people believed them, especially since Commodus often behaved like a gladiator during his reign. There were also rumors that Faustina was involved in ordering deaths, including poisonings and executions, which led many to view her as malevolent.

After her father’s death, the throne was offered to Marcus and here is where the stories about Faustina the Younger began, convincing many that she became a second Messalina. According to the "Augustan History," she behaved with extreme immorality throughout her marriage.

Four Roman nobles are specifically named as her lovers, including Tertullus. It is said that Marcus discovered this affair when an actor in the theater subtly referenced Tertullus three times, and later when he found Faustina having breakfast with him.

More reputable historians have generally dismissed these claims. Like with Messalina, while specific stories should be taken with caution, the general opinion of Faustina at the time likely had some basis in truth. Some stories in the "Augustan History" are clearly false, such as the one where Marcus was advised by Chaldean sages to kill a gladiator and bathe Faustina in his blood to cure her passion.

This story is dubious, especially since Commodus, who supposedly resulted from this affair, resembled Marcus and was born the year Marcus became emperor, making such conduct unlikely.

Other allegations, like Faustina poisoning Verus, are also false, as Verus died naturally. Historian Dio, who lived shortly after these events, does not mention any scandalous behavior by Faustina, nor do Eutropius or Aurelius Victor. Only Emperor Julian, in a general way, accuses her of dissoluteness.

The assumption of her guilt in Julian's writings and the stories from Marius Maximus, a historian close to her time, imply a widespread belief in her guilt. Capitolinus mentions that Marcus defended her against charges of misconduct and suggests that Marcus might have been either unaware of or chose to ignore her behavior. Marcus's high praise for Faustina in his "Meditations" and the altar he dedicated to her memory, where Roman maidens made sacrifices, would have been unlikely if he knew of her alleged misdeeds.

The evidence is balanced, but the heavy accusations from Marius Maximus and Julian's verdict suggest some foundation for the rumors. Marcus Aurelius, known for his grave and ascetic demeanor, might have been out of touch with Faustina, leading her to seek solace elsewhere. Her likeness in busts, medallions, and coins suggests a lack of strong character or culture, pointing instead to a weak will and sensual nature.

Commodus inherited these traits, which contributed to his disastrous reign. Despite the shame it brings to Marcus Aurelius, the evidence suggests that Commodus was indeed his son, and the blame for his faults may lie with his mother.

Faustina's Deception

The behavior of Empress Faustina during Marcus Aurelius's reign remains unclear. After Verus's triumphant return, the Empire faced significant challenges, including a devastating plague and invasions by the Marcomanni. Marcus and Verus rallied the legions to address these threats, but Verus died during the campaign in 168, likely from an apoplectic fit. Rumors of foul play by Lucilla, Faustina, or Marcus are generally dismissed.

Faustina likely accompanied Marcus on his campaigns, earning titles such as “Mother of the Camps” and “Mother of the Legions.” Her alleged misconduct with gladiators and sailors is thought to have occurred earlier. In their later years, the couple faced numerous crises, including the deaths of two children, Lucilla's widowhood, and various natural disasters. The treasury was so depleted that Marcus had to auction imperial treasures to fund the war.

In 175, Avidius Cassius revolted, supposedly at Faustina's instigation. There were rumors that Faustina secretly proposed to Cassius that he marry her if Marcus died. Marcus marched to confront Cassius but learned of his assassination by his own soldiers before he arrived. The "Historia Augusta" provides conflicting accounts of Faustina's involvement, with some sources rejecting the rumors.

“When Cassius rebelled in Syria, Marcus in great alarm summoned his son Commodus from Rome, as being now entitled to assume the toga virilis. Cassius, who was a Syrian from Cyrrhus, had shown himself an excellent man and the sort one would desire to have as an emperor, save for the fact that he was the son of one Heliodorus, who had been content to secure the governorship of Egypt as the reward of his oratorical ability.

But Cassius in rebelling made a terrible mistake, due to his having been deceived by Faustina. The latter, who was the daughter of Antoninus Pius, seeing that her husband had fallen ill and expecting that he would die at any moment, was afraid that the throne might fall to some outsider, in as much as Commodus was both too young and also rather simple-minded, and that she might thus find herself reduced to a private station.

Therefore, she secretly induced Cassius to make his preparations so that, if anything should happen to Antoninus, he might obtain both her and the imperial power.”

Cassius Dio, Roman History

Faustina's position remains ambiguous. The "Historia Augusta" mentions the rumor implicating her but also rejects it. The rejection, however, is "no more weighty than his acceptance in others." It acknowledges that Marius Maximus believed Faustina was guilty, attributing it to "a wish to defame" her. Except for the possible extension of hatred for Commodus to his mother, there is no clear reason why Maximus would slander her.

Historian Dio, close to the time, states as a "positive fact" that Faustina secretly urged Cassius to marry her and seize the throne if Marcus died. Many writers agree that Faustina, seeing Marcus as ailing and overworked, believed he wouldn't live long. With Commodus being unpromising, she sought an arrangement to stay on the throne.

While not considered gravely reprehensible, her secret negotiation "does not present her to us in an attractive light." Her later enthusiasm for punishing Cassius and his allies is also unpleasant. Letters between Marcus and Faustina, preserved in the "Historia Augusta" from Marius Maximus, suggest that Marcus often consulted Faustina on significant matters.

Marcus writes, “Come up to the Alban Mount,” after discussing the sedition, “and by the favour of the gods, we will discuss the affair in safety.” Faustina replies, “I will set out tomorrow for the Alban Mount, as you command, but I at once implore you, if you love your children, to visit these rebels with the utmost severity. The soldiers and their leaders have fallen into evil ways, and they will crush us if we do not coerce them.”

In another letter, she urges, “My mother Faustina urged your father [by adoption] Pius, at the time of the secession of Celsus, to feel first for his own family.... You see how young Commodus is, and our son-in-law Pompeianus is older and is abroad. Do not spare men who have not spared you, and would not spare me and the children if they won.”

Later, Marcus mentions reading her exhortation in his villa at Formiæ and decides not to seek further revenge on Cassius's family. He asks the Senate for moderation, stating, “there is nothing that so much commends the Emperor of Rome to the nations as clemency.” He treated Cassius’s family with great generosity.

The death of Faustina

During a voyage to the East to pacify the region, Faustina died in 175 at the foot of Mount Taurus. Marcus honored her memory beyond the customary practices, renaming a village Faustinopolis, founding a charity called “Puellae Faustinianae,” and building a temple in Rome.

He requested extraordinary honors for her from the Senate, including setting up a silver statue in the temple of Venus and a golden statue on her theater seat.

Dio gives two accounts of Faustina’s death: some say gout, others claim she committed suicide fearing her involvement with Cassius would be discovered.

“About this time Faustina also died, either of the gout, from which she suffered, or in some other manner, in order to avoid being convicted of her compact with Cassius.

And yet Marcus destroyed all the papers that were found in the chests of Pudens without reading any of them, in order that he might not learn even the name of any of the conspirators who had written anything against him and so be reluctantly forced to hate them.

Another story is to the effect that Verus, who had been sent ahead into Syria, of which he had secured the governorship, found these papers among the effects of Cassius and destroyed them, remarking that this course would probably be most agreeable to the emperor, but that, even if he should be angry, it would be better that he himself alone should perish rather than many others.

Marcus, indeed, was so averse to bloodshed that he even used to watch the gladiators in Rome contend, like athletes, without risking their lives; for he never gave any of them a sharp weapon, but they all fought with blunted weapons like foils furnished with buttons.

And so far was he from countenancing any bloodshed that although he did, at the request of the populace, order a certain lion to be brought in that had been trained to eat men, yet he would not look at the beast nor emancipate his trainer, in spite of the persistent demands of the spectators; instead, he commanded proclamation to be made that the man had done nothing to deserve his freedom.”

Cassius Dio, Roman History

The natural cause seems sufficient, as Marcus discovering Cassius’s rebellion would not put her in serious danger. Although Faustina appeared frivolous and possibly licentious early in her marriage, she seemed to become more sober as Empress. Her legacy, however, includes her troubled children, Lucilla and Commodus, who contributed to the Empire’s decline.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: