Empire Size Comparison: How did the Roman Empire Compare to Alexander’s or the Mongols?

Which empire really “ruled the map”? The answer depends on what we count and when we take the snapshot. Let's set the rules first—then follow three peaks (Rome under Trajan, Alexander’s lightning-built realm, and the Mongol high plateau) to see what the numbers can prove—and what they can’t.

Ask three atlases for the world’s largest empire and you may see the same name but different totals. That is because historians do not count claims, spheres of influence, or seas; they count dry land effectively controlled at a definable peak.

What “size” actually means—and why method matters

That apples-to-apples metric helps us compare a maritime empire with a steppe super-state, but it also demands humility. Ancient frontiers are often reconstructed from itineraries, clusters of milestones, papyri, forts, and coin finds—not neat satellite lines.

In deserts, forests, and steppe zones, authority could fade by season or distance. “Largest” is therefore a measured word, not a boast. A practical way to keep comparisons honest is to pair a single maximum area with two cautions.

- First, a range is normal where evidence is thin; if a single number circulates without a band, treat it as a rounded shorthand.

- Second, kinds of presence differ. A vast overland empire rich in grassland may contain fewer cities and fewer high-yield tax districts than a smaller maritime state stitched together by sea lanes. Raw area does not score the power of harbors, shipping routes, and coastal markets; nor does it capture how a contiguous belt of land lowers communication and transport costs. Numbers are essential—but they are only one layer of the story.

- Finally, method means being explicit about which peaks we compare. For Rome, the conventional high-water mark is AD 117 under Trajan. For Alexander, it is the 323 BCE maximum. For the Mongols, the high plateau lies in the late thirteenth century, when a continuous belt linked the Pacific, the Danube, and the Persian Gulf. These are not arbitrary choices; they are moments where controlled land reached a recognizable ceiling across the best-edited datasets and reference works.

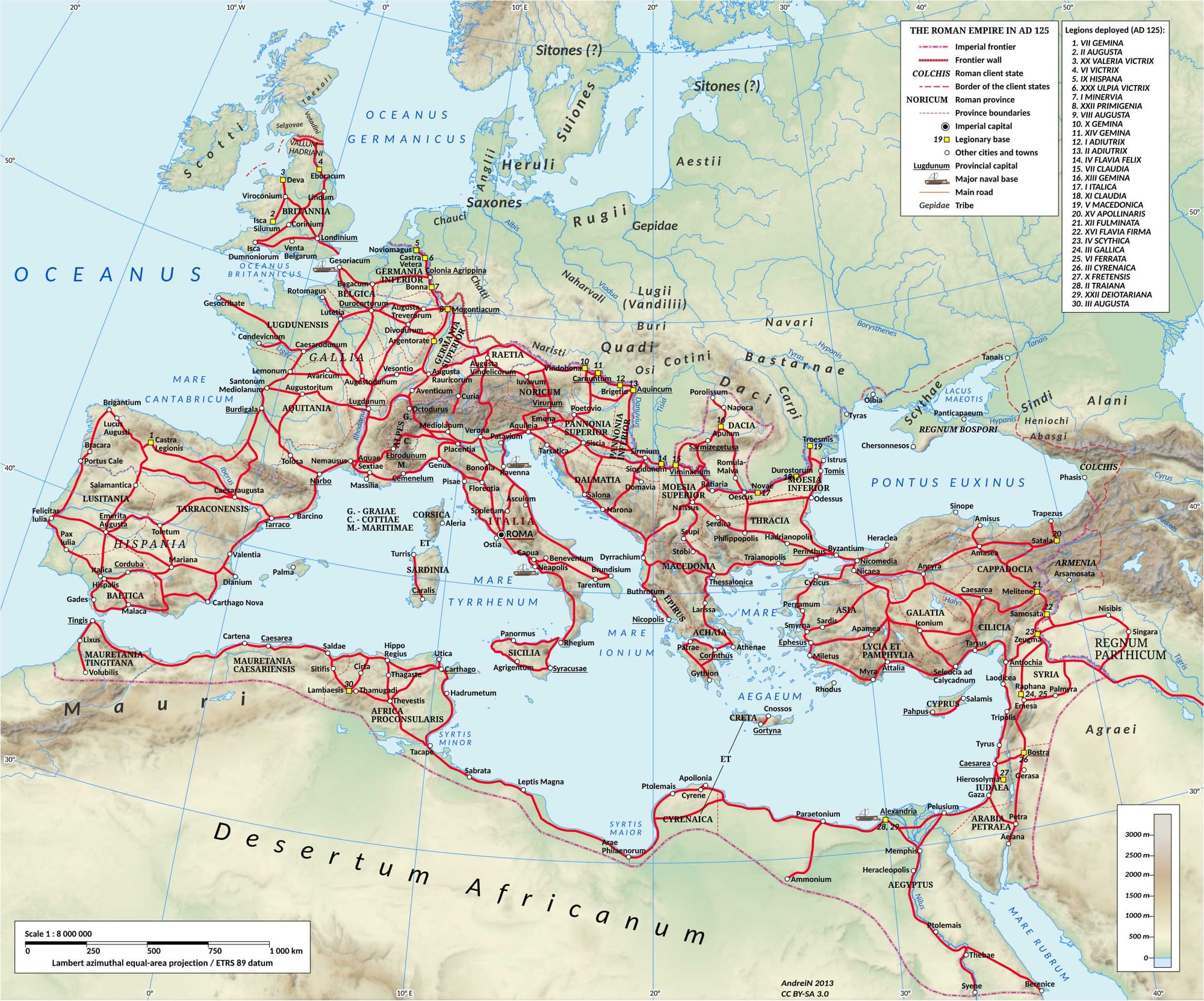

Rome at full stretch (AD 117)

When Trajan died in AD 117, Rome stood at its conventional maximum: from Britain and the Atlantic to the Euphrates, with the Rhine–Danube arc as interior frontier and a continuous African littoral from Mauretania to Egypt. On the standard yardstick, that peak is about 5 million km² (≈1.9 million sq mi) of land.

The figure hides Rome’s real advantage: a mesh of sea lanes, roads, way-stations, and administrative nodes that let the empire move messages, money, and men at speeds an inland state could not match. Sea power did not add to the land total, but it converted scattered shores into operational neighbors.

The shape of Rome’s peak also matters. Most of that territory was gathered gradually in the late Republic and early Principate, then held on a long plateau. Trajan’s conquests (notably Dacia and a brief thrust into Mesopotamia) widened the frame; Hadrian then trimmed the line to a more defensible rim.

The core endured. That longevity—rather than the raw area—explains why Rome looms large even next to empires with bigger footprints on paper. The empire sat on a dense grid of cities and provincial centers, with censuses, land registers, and fiscal districts that turned land into revenue, grain, and manpower over centuries. Read that way, Rome’s five million square kilometers (≈1.9 million square miles) are smaller than the Mongol high, but the plateau they ride on is exceptionally long.

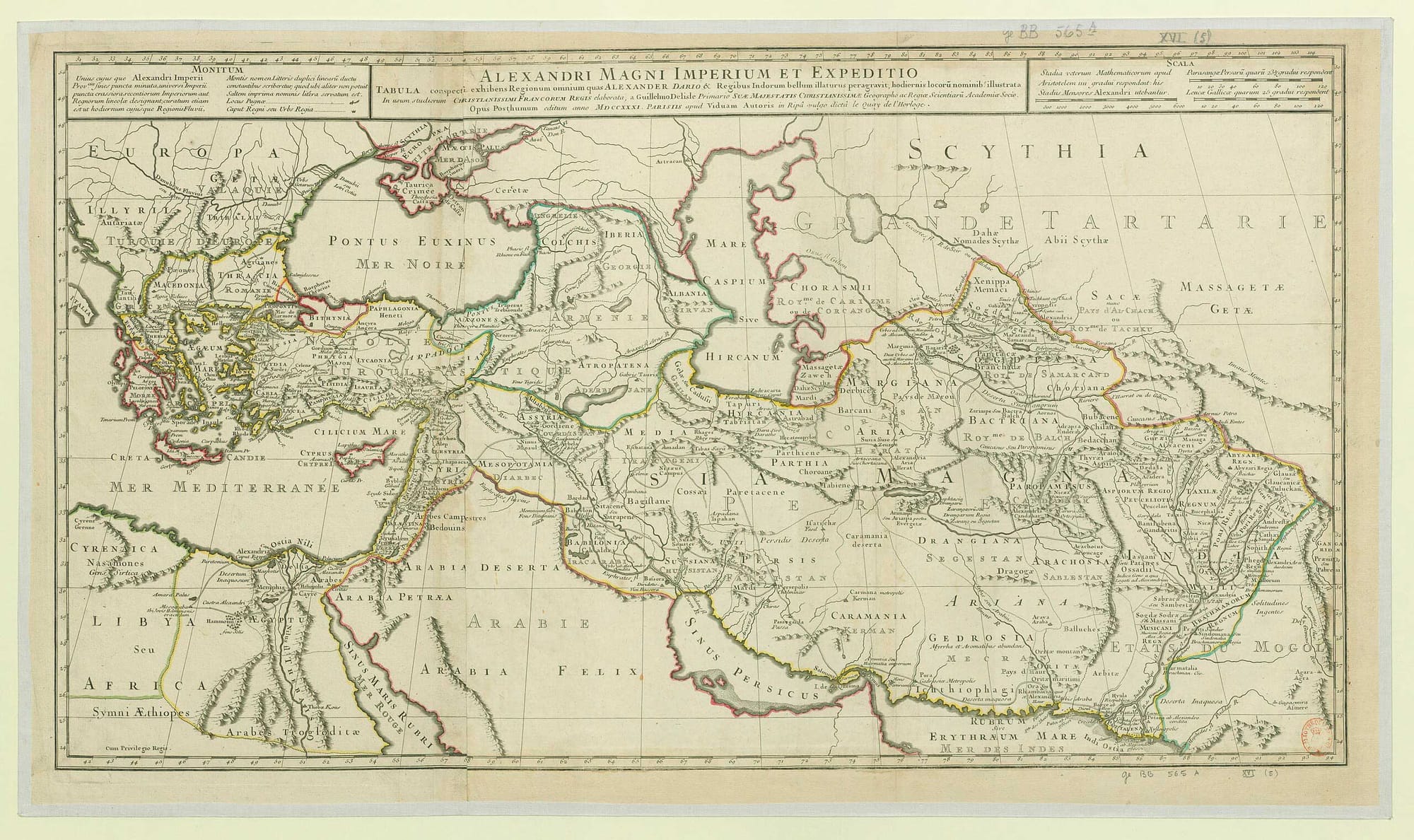

Alexander’s compressed colossus (332–323 BCE)

Between 332 and 323 BCE, Alexander folded the Achaemenid road system, ports, and satrapies into a string of rapid, decisive campaigns and briefly held a transcontinental realm from the Aegean to the Indus. Reconstructions place that maximum a little above 5 million km² (≈1.9+ million sq mi), roughly on a level with Rome’s later peak.

The difference is time-on-plateau. Alexander’s maximum is measured in months, not decades. Much of the administrative furniture was taken over intact from Persian practice or improvised on the march; cohesion depended on the king’s person and the army’s momentum.

That brevity does not erase the scale. It does change how to read the number. A quick spike is misleading if we treat it as stable capacity. One remedy is to report both the maximum and a stable maximum (what could be held for more than an instant).

Another is to look at size-over-time—how much land was controlled and for how long—which sets a short, high peak beside a somewhat smaller but longer plateau elsewhere. By those lenses, Alexander’s realm remains immense yet ephemeral: a shock-wave that re-routed trade, planted cities, and spread Greek as a language of administration and learning, but did not harden into a durable single administration at its widest extent.

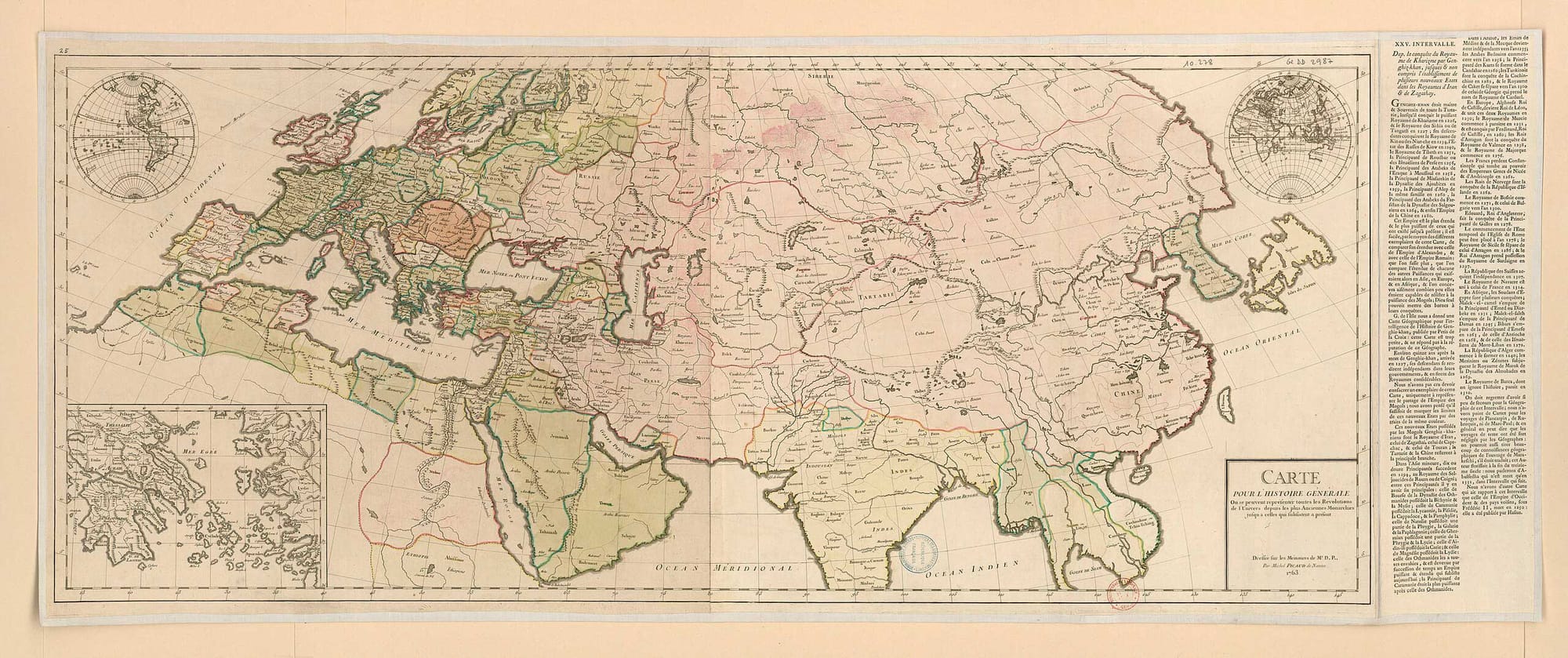

The Mongol high plateau (late 13th century)

By the late 1200s, the Mongol Empire stretched from the Pacific to the Danube and the Persian Gulf, a continuous belt of about 23 million km² (≈8.9 million sq mi)—the largest contiguous land empire in recorded history.

The qualifier matters. Overland contiguity lowers transmission costs: post-stations, remounts, and relay guards turn distances into predictable stages; armies move without waiting on fleets or fair winds; merchants and envoys can cross thousands of miles without crossing an imperial border.

Contiguity also builds an internal zone where rules, couriers, and protections travel more freely than they do between maritime basins. Unlike Alexander’s compressed spike, the Mongol footprint sat on a broad plateau.

Even as the empire divided into khanates, the aggregate geography remained immense for decades, linking East Asia, Central Asia, the Middle East, and parts of Eastern Europe in a traffic of goods, techniques, and people at scales not seen before.

On sheer land area, the Mongol high is roughly four to five times Rome’s peak and more than twice Alexander’s. But the structure behind that number differs from Rome’s coastal-city lattice. Mongol governance leveraged mobility, delegated power to Chinggisid houses, and drew revenue from trade corridors and subject agrarian zones rather than from a dense network of Mediterranean ports. In other words, the same number can point to a different kind of reach: continental corridors rather than coastal nodes.

Ratios, ranges, and what big maps hide

Set the three peaks on one line and a tidy comparison emerges:

Rome (~5 million km² (≈1.9 million sq mi)) ≈

Alexander (~5+ million km² (≈2.0+ million sq mi))

The ratios are stark: the Mongol maximum is roughly 4–5× Rome; Rome and Alexander are broadly comparable in raw land area. Yet a single number can mislead if we forget what it omits. Rome’s sea power stitched noncontiguous shores into one operating space; land-area tables do not score that.

Alexander’s total compresses a conquest whose administrative hardening was still in progress; stabilizing that much land would have taken a generation. The Mongol figure includes vast low-density grasslands and deserts whose tax yield and urbanization could not match Italy or coastal Syria; their value lay in movement, not municipal density.

Ranges are the other reason for caution. In deserts, oases, and seasonal pastures, “control” can shrink or expand with rains, harvests, and leadership. Responsible datasets mark uncertainty rather than pretend to single-point precision: dry land only; effective, not merely claimed authority; and a definable peak year or short span.

Where evidence thins, the number becomes a band. For readers, the test is transparency: can we see how the figure was constructed, which maps and texts underwrote it, and how disagreements were handled? When those rules are clear, the ratios above remain robust—without pretending that ancient borders ever behaved like neat survey lines.

More of the ancient peaks: Persia, Byzantium, the Ottomans, and China

At its widest reach in the early fifth century BCE, the Achaemenid Persian Empire stretched from the Balkans and Egypt to the Indus. Most comparative datasets place this maximum near ~5.5 million km² (~2.1 million sq mi), which makes Persia broadly comparable in raw land to Rome’s later high water mark, though configured along continental corridors rather than a maritime rim.

The Byzantine Empire presents a different profile. Under Justinian in the mid-sixth century, the eastern Roman state briefly reunited large tracts of the Mediterranean littoral; the usual estimate for that moment is ~3.4 million km² (~1.3 million sq mi). Its territorial story is cyclical—recovery, contraction, and recovery again—which is why a single number should be read as a snapshot rather than a sustained plateau.

The Ottomans, emerging from Anatolia into the Balkans and the Arab world, reached a maximum commonly given as ~5.2 million km² (~2.0 million sq mi) between the late sixteenth and late seventeenth centuries. In raw land this places them near Alexander’s and Rome’s totals, though the balance between Mediterranean coasts and inland provinces differs markedly across the three.

Several pre-modern Chinese dynasties also attained world-class scales. The Han realm is typically placed around ~6.0–6.5 million km² (~2.3–2.5 million sq mi), while Tang reconstructions often center near ~5.4 million km² (~2.1 million sq mi). As with all ancient figures, these are rounded bands derived from atlas-based assessments of controlled land at a definable peak; frontier zones that shifted with ecology and local allegiance account for the range.

Read against the Roman, Alexander, and Mongol peaks, the pattern is consistent: Rome’s raw area sits below the very largest ancient totals, yet its longevity, density of cities, and sea control put it on a long, steady platform that land-area tables do not register on their own.

The modern era: Spain, Portugal, Russia, Britain

By the late eighteenth century the Spanish Empire spanned the Atlantic world with possessions in the Americas, Europe, Africa, and Asia. The accepted figure—~13.7 million km² (~5.3 million sq mi)—aggregates dispersed territories linked by oceanic shipping, metropolitan finance, and administrative law rather than by a contiguous land belt.

The Portuguese case highlights a frequent problem in the lists. If one focuses on the later “Second Empire” in Africa and Asia, estimates cluster near ~5.5 million km² (~2.1 million sq mi); if one folds in Brazil prior to 1822, totals jump significantly. The gap reminds us that “claimed” and “effectively controlled” are not synonyms, and that a date stamp is essential to any comparison.

On the Eurasian landmass, the Russian Empire reached approximately ~23 million km² (~8.9 million sq mi) in the late nineteenth century, rivaling the Mongol total in scale, though operating with very different institutions, demography, and logistics.

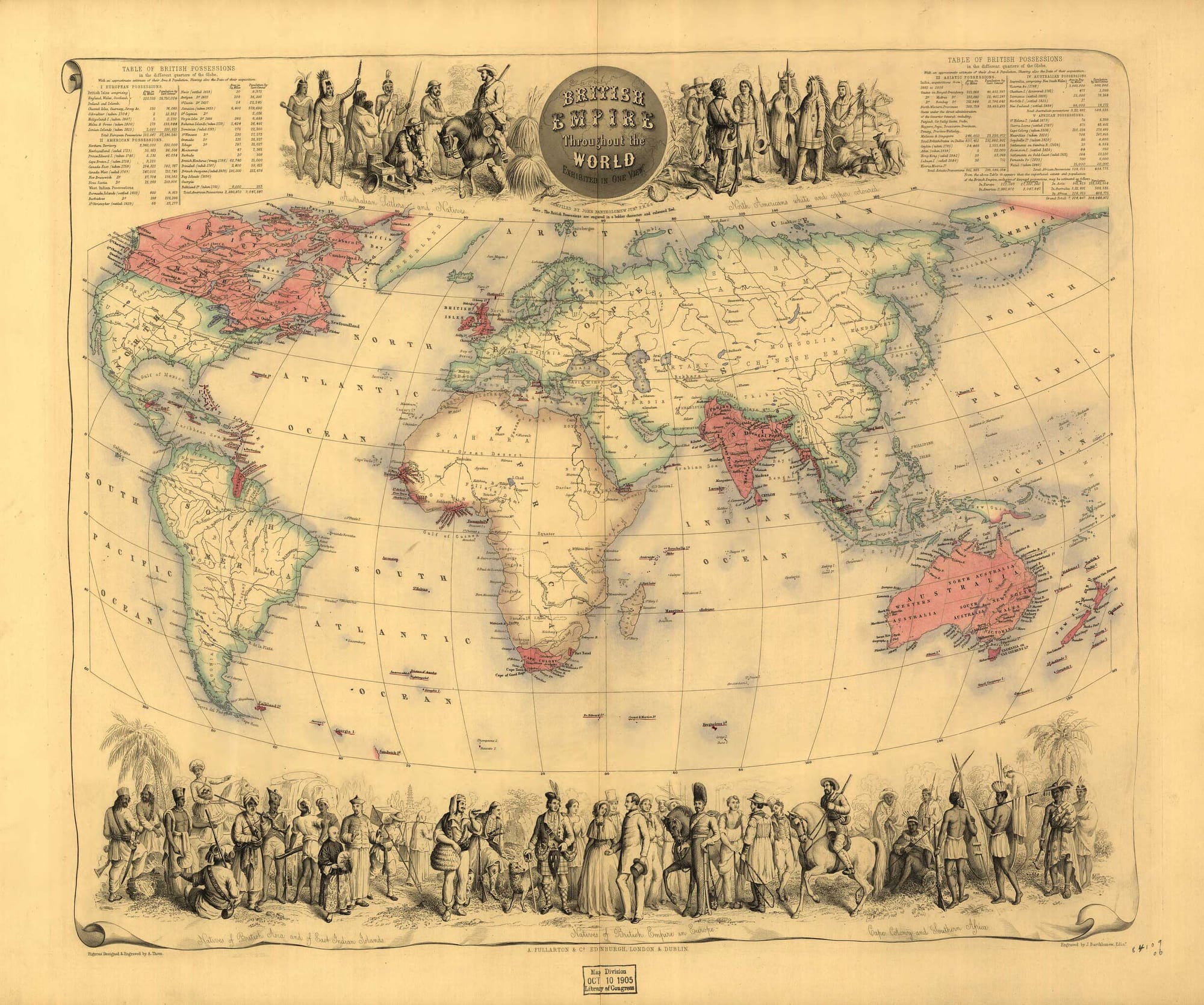

The British Empire, measured in the early twentieth century, remains the largest aggregate by land area in the standard compilations at ~35.5 million km² (~13.7 million sq mi)—often summarized as “nearly a quarter of the Earth’s land.”

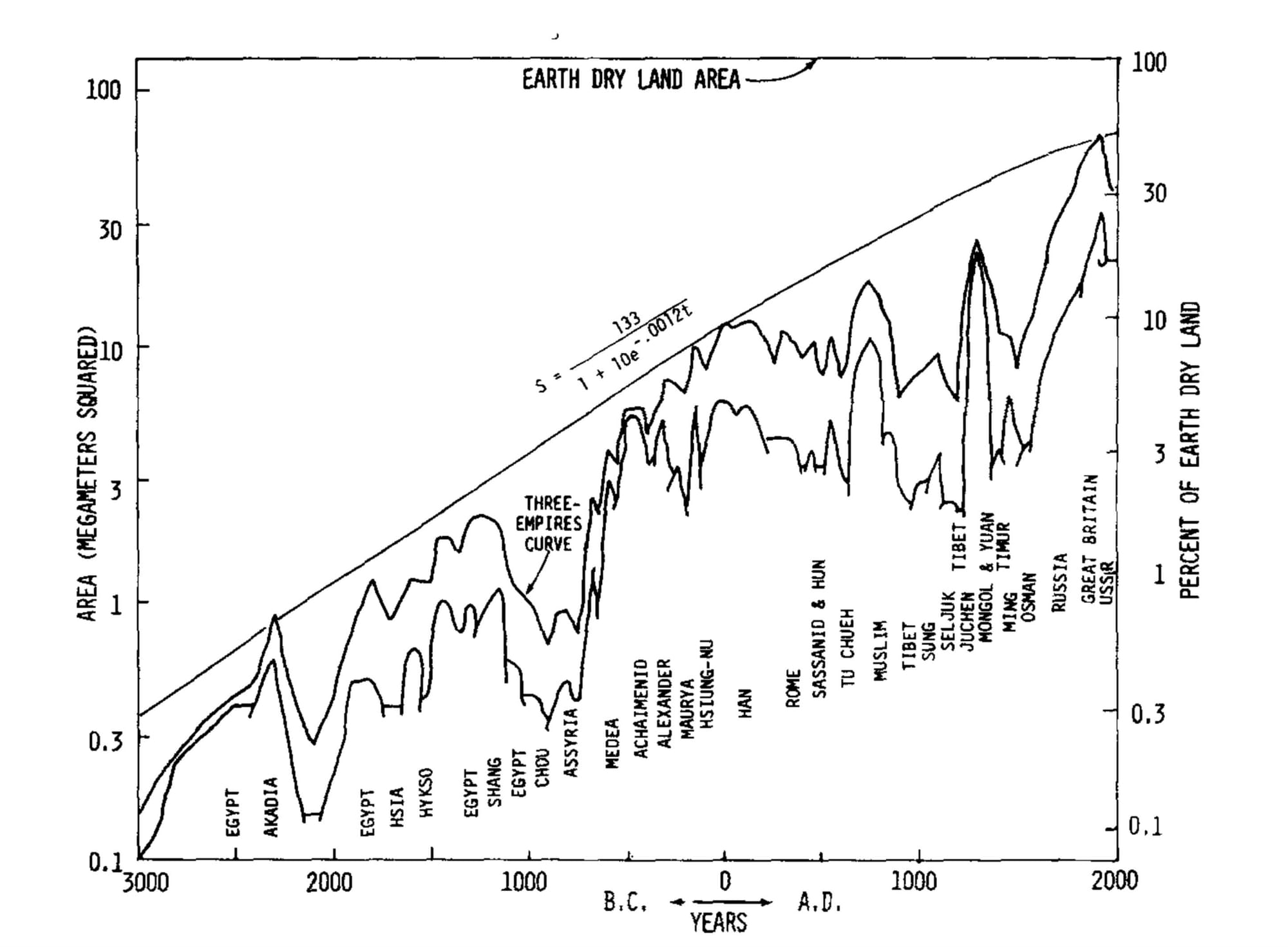

These modern totals mark a shift in what “size” means: maritime empires stitched far-flung regions by sea power and communications, while continental empires expanded rail, road, and administrative grids across interior spaces. The numbers sit on different kinds of geography, and the kind matters. (Size and Duration of Empires: Systematics of size, by Taagepera, Rein; Size and Duration of Empires: Growth-Decline Curves, 3000 to 600 B.C., by Taagepera, Rein)

Judged strictly by controlled dry land at a clearly defined peak, the Mongol Empire remains the outlier, far above Rome and Alexander and above most other ancient polities as well. Yet the headline figure never exhausts the story.

Rome’s smaller number rides a much longer plateau sustained by urban density, fiscal districts, and maritime logistics; Alexander’s footprint is immense but brief, a crest that needed time to harden; the other ancient cases occupy their own niches along the same axes of area, duration, and administrative depth.

British (~35.5 million km² (≈13.7 million sq mi)) »

Russian (~23 million km² (≈8.9 million sq mi)) ≈

Mongol (~23 million km² (≈8.9 million sq mi)) »

Spanish (~13.7 million km² (≈5.3 million sq mi)) »

Han (~6.0–6.5 million km² (≈2.3–2.5 million sq mi)) »

Achaemenid Persia (~5.5 million km² (≈2.1 million sq mi)) ≈ Portuguese (~5.5 million km² (≈2.1 million sq mi)) »

Tang (~5.4 million km² (≈2.1 million sq mi)) »

Alexander (~5+ million km² (≈2.0+ million sq mi)) ≈

Ottoman (~5.2 million km² (≈2.0 million sq mi)) »

Rome (~5.0 million km² (≈1.9 million sq mi)) »

Byzantine (~3.4 million km² (≈1.3 million sq mi))

Modern empires add a further shift in scale and mechanism: Spain and Portugal as ocean-bound networks, Russia as a continental expanse, Britain as the largest maritime aggregate in the record. A careful comparison therefore pairs the maximum with its lifespan and the means that held it together—whether ports and convoys, posts and remounts, or roads and census districts. The map supplies the number; the history underneath supplies its meaning.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: