Emperor Decius: Persecutor of Christians or Restorer of Rome?

In just two years, Emperor Decius reshaped Roman religious policy, revived ancient offices, and died fighting on the empire’s edge. Long remembered as the first great persecutor of Christians, his reign reveals a deeper story—one of ritual, restoration, and a desperate bid to save a crumbling world.

In the shadow of a fractured empire and the memory of greater men, Decius stepped onto the Roman stage not as a conqueror, but as a restorer. Styling himself Trajanus—a name soaked in imperial glory—he envisioned a return to Roman virtue, tradition, and divine favor.

Yet his most ambitious decree, an empire-wide command for sacrifice to the old gods, would earn him a darker legacy. Christians remembered him as the first great persecutor. Historians, however, now ask: was Decius truly driven by cruelty—or by desperation to save a dying world?

A Crisis Demands a Savior

The mid-third century was a time when Rome teetered on the edge of collapse. Borders were under siege, emperors rose and fell in rapid succession, and the old rhythms of Roman life—military discipline, religious piety, civic duty—seemed to be crumbling.

Into this chaos stepped Decius, a seasoned senator and general from the Balkan provinces, proclaimed emperor by his troops in 249 after defeating Philip the Arab. His ascent was not driven by personal ambition alone; it was born of necessity. The empire needed order, and Decius believed he could provide it.

He was no innovator. Quite the opposite—Decius looked backward, drawing on the memory of better times.

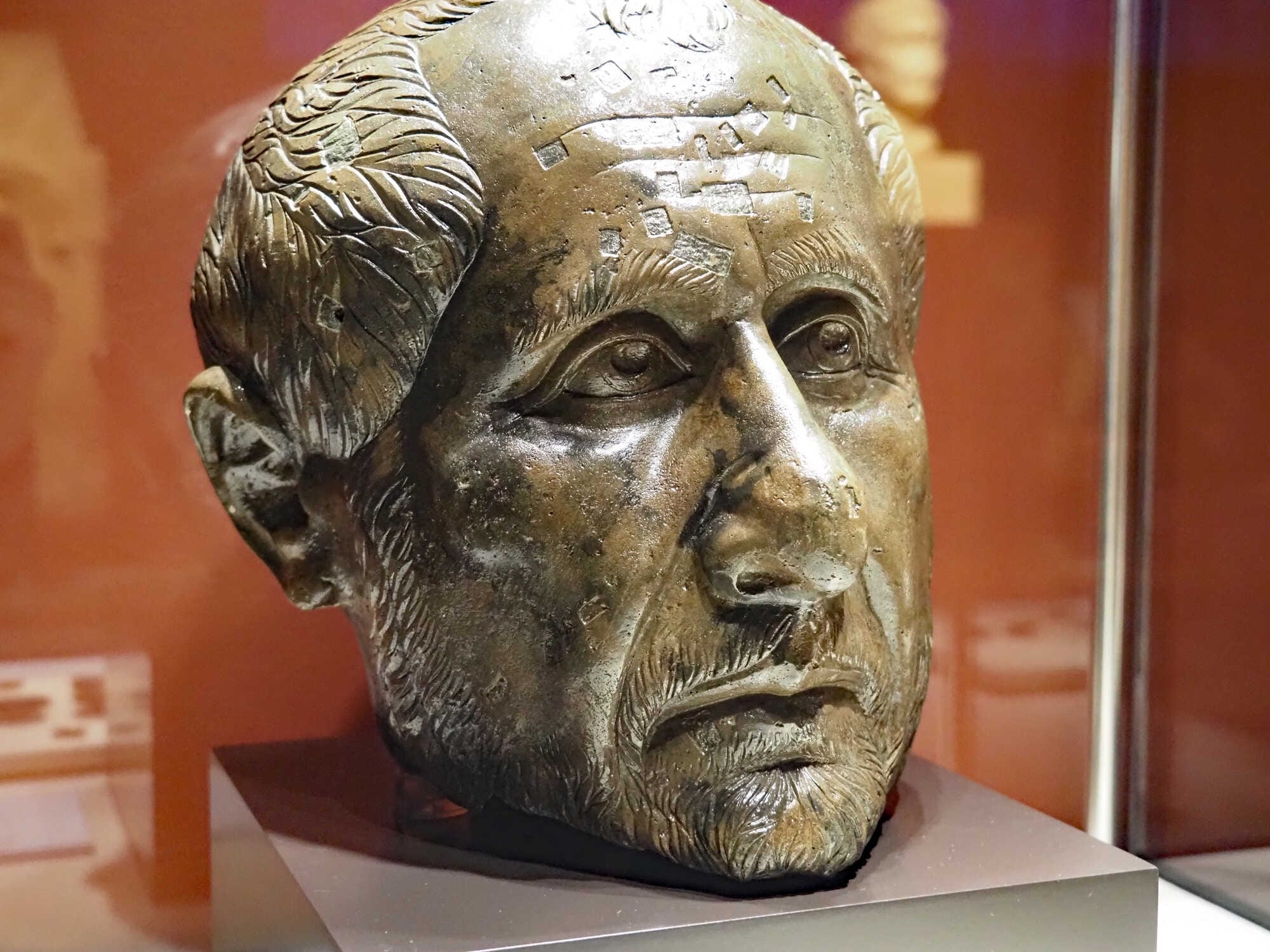

A closeup of a bust of Roman Emperor Trajan Decius. Credits: F. Tronchin, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

He took the name Traianus in deliberate homage to Trajan, the emperor still remembered as the embodiment of Roman strength and justice. This was not empty flattery of the past, but a calculated move to evoke an era when Rome’s gods were honored, its armies feared, and its values intact. To Decius, the solution to present instability lay in restoring the foundations of the old Republic—its morality, its religion, and its unity.

One of his first acts was to revive the long-dormant office of the censor, an institution once charged with upholding public morals and overseeing the Senate. It was a symbolic gesture that reflected his wider agenda: Rome would be healed not by new doctrines or reforms, but by recovering its ancient soul.

In a time of plagues, food shortages, and foreign threats, Decius envisioned himself not merely as a ruler, but as a restorer—princeps restitutor, a title that would soon be etched into coins bearing his name.

Faith on Trial: The Sacrificial Edict

In either the final days of 249 or the opening of 250 CE, an imperial decree swept through the Roman Empire—an edict unlike any before. It commanded every citizen to make a public sacrifice to the Roman gods, taste the sacrificial meat, and pour a libation in the emperor’s name.

These acts, so ordinary to traditional Romans, became the basis for a sweeping campaign of ritual conformity. From Alexandria to Hispania, civic life was suddenly reordered around a test of loyalty—measured not in words or taxes, but in ash and incense.

To administer the edict, Decius ordered the formation of sacrificial commissions, panels of local officials that operated in cities, towns, and even rural villages. Compliance was recorded through written certificates called libelli—physical proof that the bearer had performed the proper rites.

The process was standardized: make the offering, taste the meat, pour the wine. Those who refused were brought before magistrates, imprisoned, tortured, or executed. But this machinery, though brutal in effect, was not driven by sadism. It was designed to secure unity—religious, civic, and imperial—in a time when Rome’s very soul seemed under siege.

For Christians, the edict posed an impossible choice: renounce their God or die. Some fled, others broke under pressure, and many held firm, becoming martyrs remembered in church calendars for centuries to come.

Yet Decius did not single out Christians in the edict’s language. Its scope was universal. All were required to sacrifice—not because of their beliefs, but because the emperor demanded shared ritual as a safeguard for Rome’s future. It was less an act of targeted persecution than a test of Roman identity.

Persecutor or Traditionalist? Rethinking Decius’ Motives

For centuries, Christian writers portrayed Decius as a villain—a successor to Nero and Diocletian, a man who tried to stamp out the faith by force. Eusebius, the earliest major church historian, framed the edict as a deliberate persecution of Christians, part of a satanic assault on the true religion.

“The cruelty of the tortures surpassed all description.”

Eusebius

This portrayal became deeply rooted in Christian memory. But modern historians are no longer so certain. When the language of the edict is examined—stripped of later theological interpretation—it tells a different story: one of enforced ritual unity, not of extermination.

No known document from Decius himself, or from imperial authorities, explicitly names Christianity as the target. Instead, the decree applied to all citizens, requiring them to demonstrate public piety in a moment of collective crisis. As historian Torstein Jørgensen notes:

“The motive behind the edict was not a desire to suppress Christianity as such, but rather an attempt to reassert the traditional religious foundations of Roman society.”

Christians suffered greatly under it, but not because they were the intended victims—instead, because they alone, as a group, refused to participate in the rituals required of everyone else.

Credits: The Met Fifth Avenue, Public domain

Image #2: A painting showing Saint Fabian, Saint Sebastian and Saint Roch, the two first famously persecuted and martyred under Emperor Decius and Emperor Diocletian.

Credits: Lluís Ribes Mateu, CC BY-NC 2.0

This distinction matters. Decius was not a religious ideologue but a traditionalist, working to restore favor with the gods through universal acts of devotion. His edict may have caused widespread arrests and executions, but the machinery behind it was civic and religious, not genocidal.

The suffering it inflicted was tragic, but its purpose—at least from Decius’ perspective—was to heal Rome, not to destroy dissent. In hindsight, it became one of the earliest moments when state ritual collided fatally with Christian conscience. But it began, not as persecution, but as policy.

Death at Abritus and the Shadow of Legacy

In 251 CE, Emperor Decius faced a new threat—not from within the empire, but from beyond the Danube. The Gothic leader Cniva had crossed into Roman territory, and the emperor moved to confront him. In the swamps near Abritus, in modern-day Bulgaria, Decius and his son Herennius Etruscus led their legions into battle.

The result was catastrophic. Both father and son were killed—Decius becoming the first Roman emperor to perish in combat against a foreign enemy. The bodies were never recovered. Rome was left stunned.

Despite his death in the field, Decius was not immediately condemned. The edict of sacrifice was not reversed, and his successor Trebonianus Gallus even maintained a tolerant stance toward those who had carried out Decius’ policies.

His image endured on coins, often alongside deified emperors of the past—a subtle affirmation of his efforts to place himself in that lineage. The persecution he inadvertently launched left deep scars, especially in Christian memory, but in political terms, Decius’ reign passed into the wider turbulence of the century without further censure.

In the broader scope of Roman history, Decius stands at a crossroads. His death marked not only a military disaster, but the end of a moment when Rome attempted, through religious uniformity, to restore its identity. His actions echoed long after his fall—not because they succeeded, but because they revealed just how fragile the empire’s foundations had become. (The Decian Persecution: Reconsidering its Cause and Nature, by Torstein Jørgensen)

Sacrifices on Paper: The Bureaucratic Machinery Behind the Decian Persecution

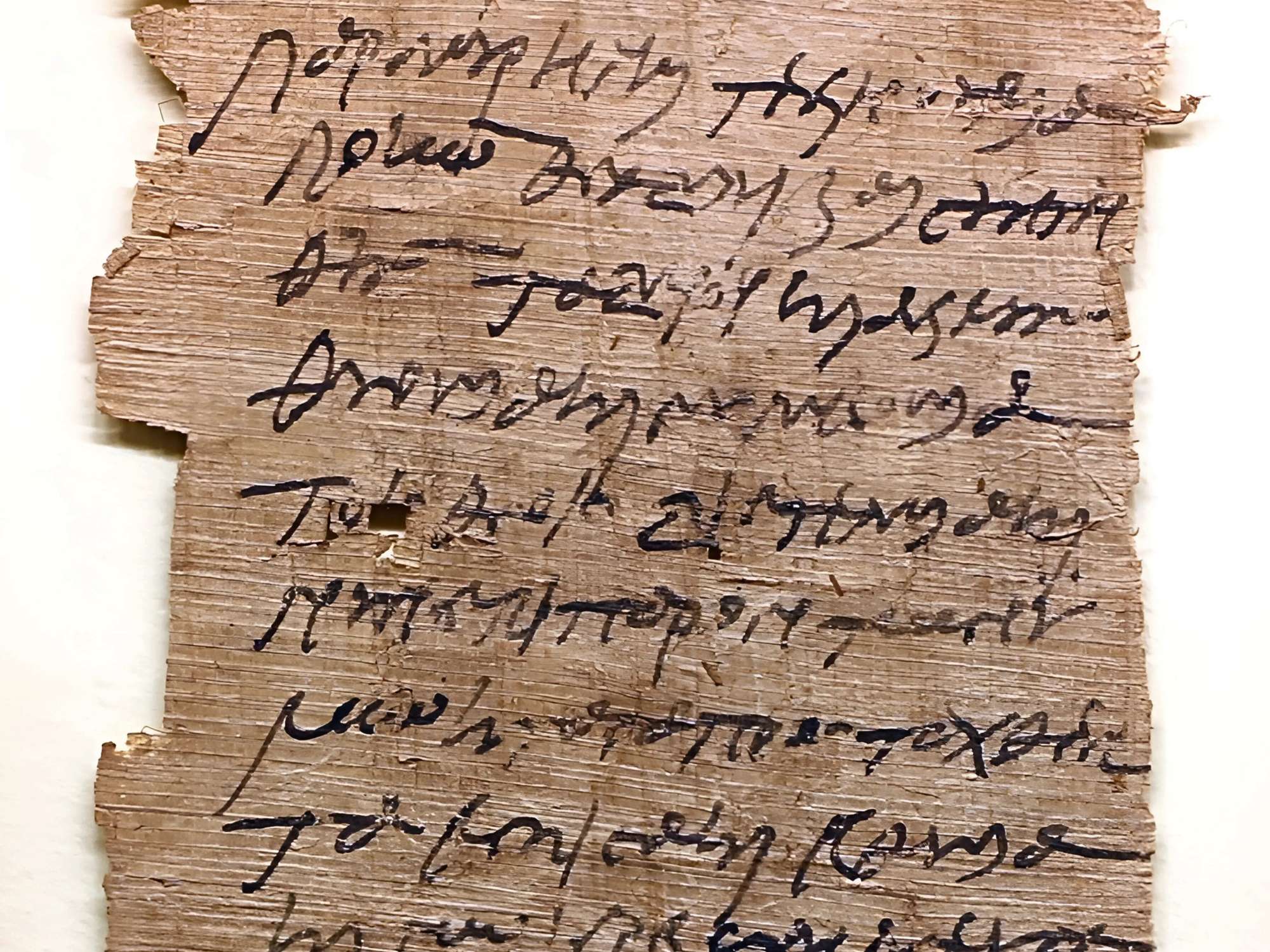

Though the Decian edict struck terror into Christian communities, its execution was not chaotic. It was bureaucratic. Across the empire—but most tangibly in Egypt—a paper trail of compliance emerged: the libelli, which as aforementioned certificates a confirmation that an individual had sacrificed to the gods in accordance with imperial orders.

These documents, small in size but immense in implication, reveal the administrative backbone of a policy often remembered only for its brutality.

Part of a papyrus with libell of the Decian persecution, with the certification of having sacrificed to the pagan gods for 2 women, June 14, 250 AD. Credits: Sailko, CC BY-SA 4.0

Most surviving libelli come from the Egyptian towns of Theadelphia and Arsinoë, dating to the year 250 CE. While their formula varied slightly, they followed a clear structure: the petitioner’s declaration that they had sacrificed, accompanied by a record of the offering, and endorsements by witnesses and local officials.

Three distinct hands are often present on each document: one writing the text, and two signing to verify the act. This wasn’t merely a matter of local reporting—it was a layered verification process designed to resist forgery and guarantee uniform compliance.

Local administrators played an essential role. In Theadelphia, the names of a grammateus and a commissioner recur across several certificates, hinting at a small team conducting mass documentation.

In Arsinoë, the officials included a prytanis, possibly the town’s leading magistrate. These layers of bureaucracy show that the edict wasn’t just law—it was a logistical enterprise.

Curiously, the petitioners named in these documents do not include overtly Christian names. Whether this reflects a real absence of Christians in the records, or the tendency of Christians to refuse the process altogether, remains debated.

Either way, the survival of these documents provides an extraordinary window into how Decius' policy was experienced at the level of everyday life—through paperwork, not just persecution.

One night, by lantern light, he carried a child who grew so unbearably heavy that he struggled to move. “You have carried the weight of the world,” the child revealed, “for I am Jesus Christ.” His name, Christophoros—Greek for “Christ-bearer”—remains associated with safe travel; for centuries, it was believed that gazing upon his image would bring protection for the day.

Around 250 CE, during Emperor Decius’s persecution, Christopher was martyred—tortured and beheaded. This is alluded to in the painting by the severed head pierced by a knife hanging from a dead tree branch. Stylistically and iconographically, Van Mandijn’s composition follows the path of Hieronymus Bosch, blending fantastical detail with moral allegory.

The vivid, lifelike landscape teems with bizarre creatures crawling, flying, and swimming—symbolic embodiments of the Seven Deadly Sins that ceaselessly tempt humankind.

Analysis by Dr. Alexey Yakovlev

Restorers of the Provinces: Decius and His Family on the Frontier

As mentioned above, between 249 and 251 CE, the Danubian frontier transformed into the beating heart of imperial attention. The provinces of Dacia, Upper Moesia, Lower Moesia, and Thrace—battered by waves of Gothic and Carpic incursions—became the primary arena of Emperor Decius’ activity.

But he did not face the crisis alone. Coins and inscriptions across the region testify to the physical presence not only of the emperor, but also of his wife Herennia Etruscilla and their son Herennius Etruscus. Their presence in these volatile territories was not ceremonial—it was part of a coordinated imperial response to instability on multiple fronts.

Local coinage from Dacia and Upper Moesia reveals a carefully curated message. These issues, distinct from those struck in Rome, featured images of Victoria, personifications of the provinces, and symbols of abundance like cornucopias and wreaths.

The consistency of these motifs reflected a calculated attempt to inspire confidence and suggest resilience in the face of chaos. The titles Restitutor Daciarum and Dacicus Maximus, preserved in inscriptions from Apulum and Hispania, hint at successful operations by Decius that went unrecorded in narrative sources but were commemorated by the provinces themselves.

Road repair projects and milestone inscriptions also traced the movements of the imperial family. Inscriptions from the key road between Scupi and Naissus, and across Dacia, suggest Decius not only commanded from afar but walked the ground himself.

The Empress Herennia, bearing the title mater castrorum—a designation used by women actively engaged in military life—was honored in Thrace and Lower Moesia. Her role, far from passive, appears to have mirrored the precedent set by imperial women of the previous century who accompanied their husbands in military campaigns.

A particularly intriguing case concerns their younger son, Hostilian. A medallion struck at Viminacium in Upper Moesia shows him as Caesar—suggesting that he, too, may have visited the province.

This challenges the conventional narrative that Hostilian remained in Rome while his father and brother led the war effort. If true, this temporary absence of all male members of the imperial house may explain the brief usurpation of Valens in 251—a moment of opportunism in a capital left unguarded.

In all, the pattern is clear. The Decian dynasty was not operating from a distance. It moved with the army, appeared in provincial mints, and responded visibly to crisis in Rome’s vulnerable borderlands.

Though history would later reduce Decius to the emperor who persecuted Christians, the record from the Danubian limes tells another story: one of active governance, coordinated imperial presence, and a desperate effort to hold the empire’s edge together as everything threatened to fall apart. (Emperor Trajan Decius and His Sons on the Lower-Danubian Limes (AD 249–251), by Lily Grozdanova)

In the short span of his reign, Decius imposed one of the most far-reaching religious policies Rome had ever seen. Yet beneath the traditional image of a persecutor, the sources reveal a more complex figure—one who looked to the past for solutions, who sought civic unity through shared ritual, and who governed not just from Rome, but from the frontier.

His edict, preserved in the libelli of provincial Egypt, and his presence, inscribed in stone across the Danubian provinces, show an emperor trying to reassert control in a world that seemed to be slipping away. Whether remembered as a restorer or remembered as a threat, Decius left behind a legacy not of ideology alone, but of crisis management—written in ink, stone, and blood.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: