Contrary to What you Think, Not all Romans Spoke Latin. Here's What they Actually Spoke.

Across the Roman world, daily interaction followed rules that were rarely written down. Power, identity, and belonging were negotiated through habits people learned by listening.

Rome governed through roads, laws, and armies—but daily life unfolded through something far less uniform. Across cities, villages, camps, and marketplaces, people negotiated, argued, prayed, joked, and commanded in ways that were instantly understood by those around them, yet unfamiliar to outsiders.

This constant exchange shaped how authority was exercised, how communities formed, and how the Empire functioned at its most ordinary level. To understand Rome as it was lived, it helps to listen first—not to what was written, but to what was spoken.

What People Actually Spoke in the Roman Empire

Across the Roman world, daily communication rarely took place in a single language. Movement was constant: soldiers were transferred, merchants travelled, slaves were relocated, and officials circulated between provinces. As a result, most communities were exposed to more than one language, and many people developed at least a functional ability to operate across linguistic boundaries.

There was no attempt by Roman authorities to enforce a single spoken language. Latin carried legal and administrative authority, but its spread depended largely on context and convenience rather than obligation. In the eastern Mediterranean, Greek already functioned as a shared language of communication and continued to do so under Roman rule. Latin remained present in official settings, but it did not displace Greek in everyday life.

Competence in more than one language varied widely. Some individuals were fluent, while others used a second language only in limited and familiar situations. Full mastery was not required. Communication depended on practical ability rather than formal correctness, especially in settings such as markets, military camps, and administrative exchanges. Partial bilingualism was sufficient for daily needs.

Language choice was shaped by situation and audience. Different languages carried different social meanings, and speakers adjusted accordingly. Using Latin could signal authority or official status; using a local language could signal familiarity or accommodation. Switching between languages was common and often deliberate, reflecting social awareness rather than confusion.

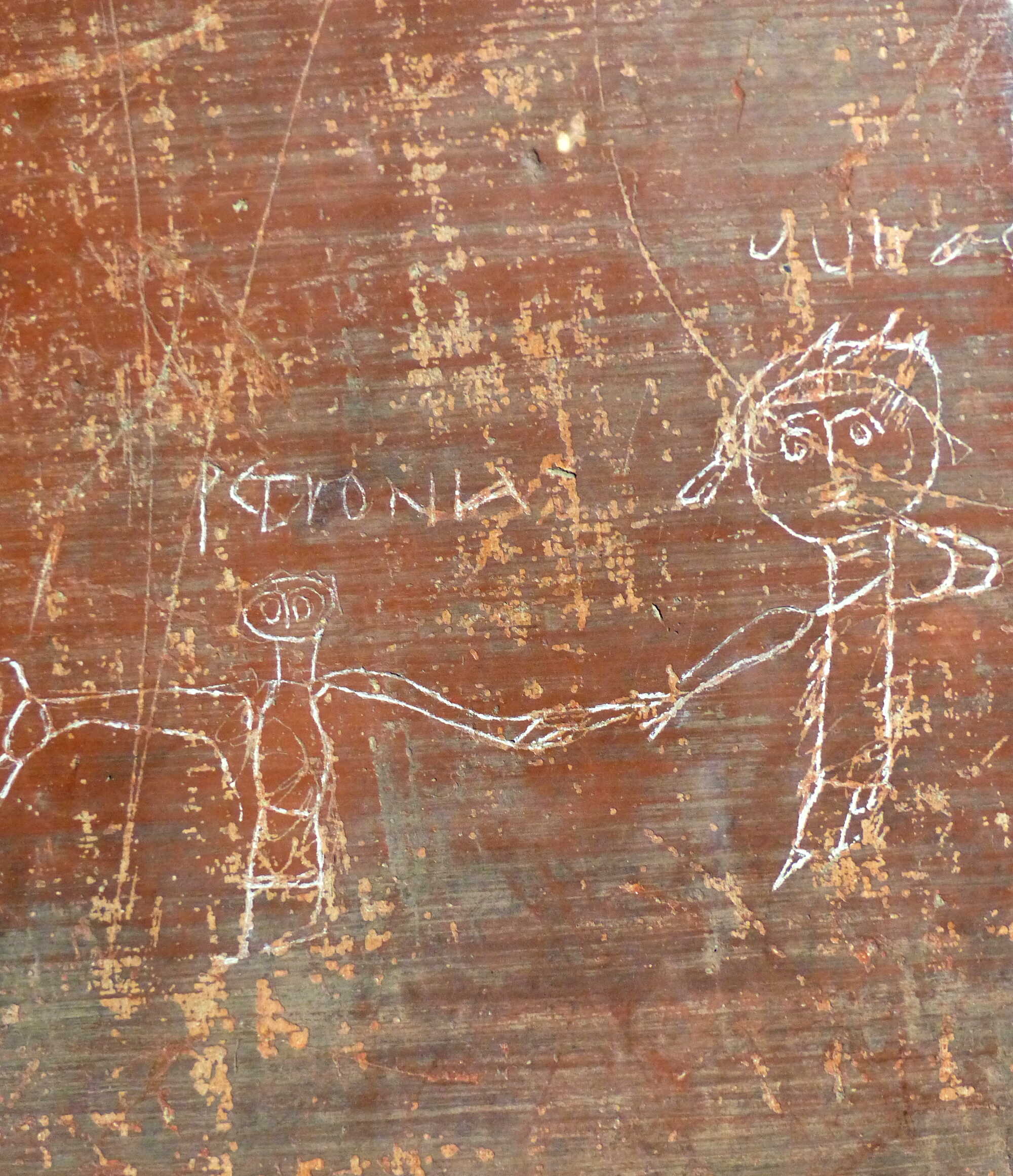

Multilingual practice was not confined to educated elites. Evidence from inscriptions, private documents, and informal writing shows that ordinary people also navigated linguistic diversity. Shopkeepers, craftsmen, soldiers, and local officials operated in environments where more than one language was present, and their communication reflects this flexibility.

Contact between languages influenced how Latin itself was spoken. As Latin circulated through different regions, it absorbed local features and developed distinct regional forms. Long before later linguistic divisions became visible, spoken Latin already varied considerably from place to place, shaped by the languages alongside which it was used.

The Roman Empire functioned through this adaptability. Communication did not depend on uniform speech, but on shared expectations and the ability to make oneself understood. Linguistic diversity was not an obstacle to cohesion; it was a normal condition of life within an empire that spanned continents. (“Bilingualism and the Latin language” by J.N. Adams)

What Multilingualism Looked Like in Practice

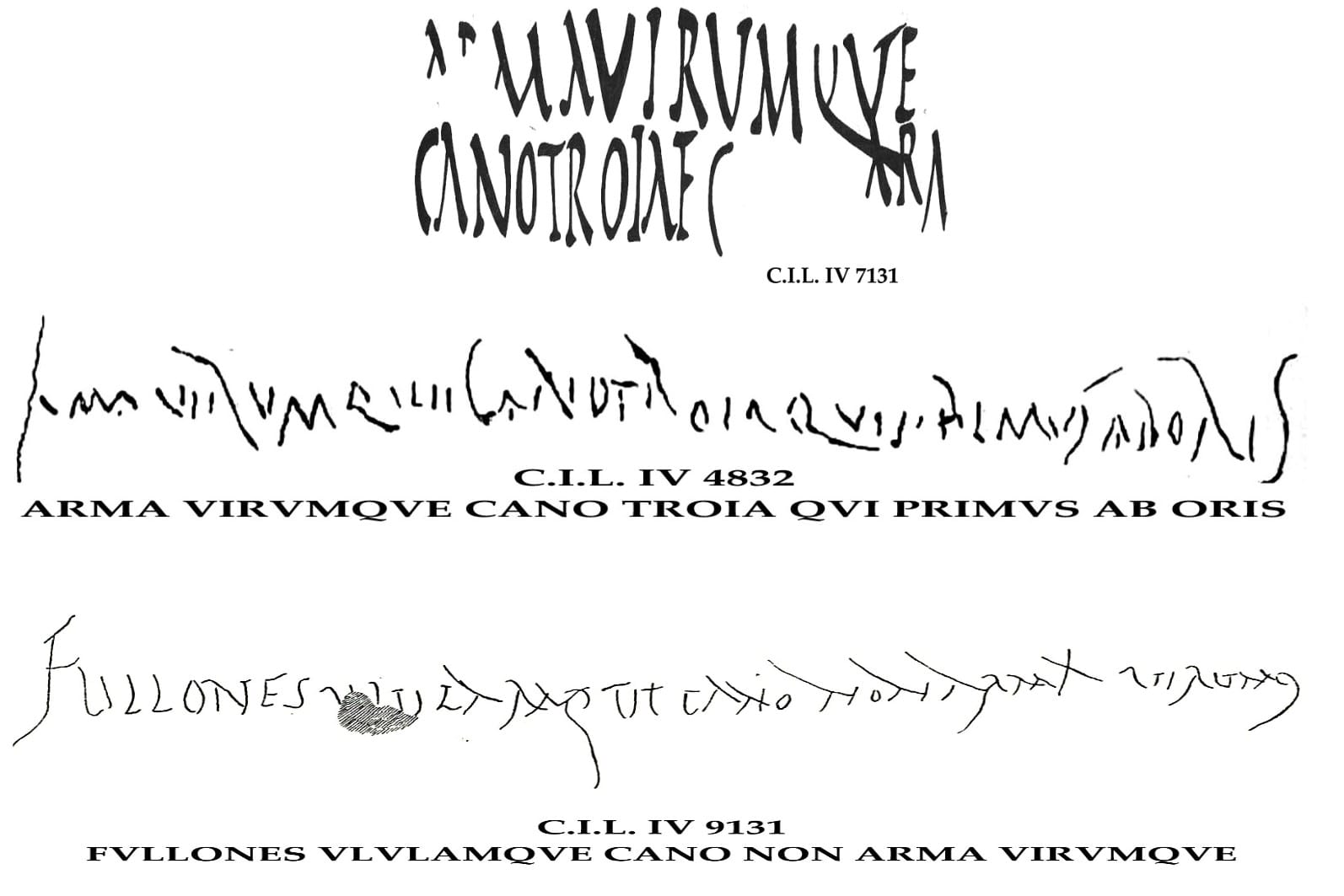

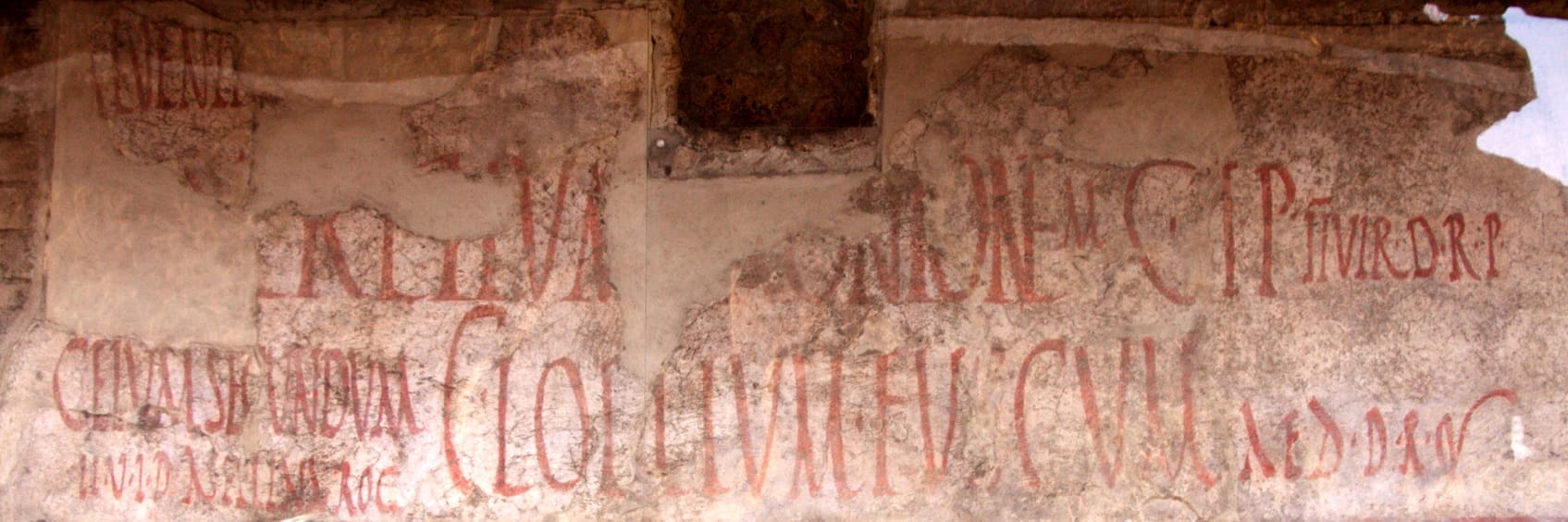

Language diversity in the Roman world was not an abstract condition. It was visible in stone, metal, and paint—on tombstones, public buildings, and everyday objects. In many places, people did not choose one language over another. They used several at once, each serving a different purpose.

One striking example comes from northern Britain. Near a Roman fort, a tombstone was erected for a woman named Regina. The inscription speaks in two voices. One is in Latin, identifying her status and social ties. The other is written in Palmyrene, a form of Aramaic associated with Syria. The languages do not simply repeat one another. Each carries a different emotional and cultural weight. Latin communicates status to the local and imperial audience. Palmyrene expresses personal identity and grief, even though very few people nearby could read it. The choice to include it was symbolic, not practical.

Elsewhere, multilingualism appeared in public spaces. In North Africa, buildings were sometimes marked with inscriptions in Latin and Punic, and occasionally Greek as well. These were not translations for the illiterate. They addressed different groups who shared the same space. Latin spoke to imperial authority; Punic to local tradition; Greek to wider Mediterranean culture. The presence of multiple languages on the same monument reflects coexistence, not transition.

Multilingual practice was not limited to formal inscriptions. Some texts mix languages so closely that no single one clearly dominates. Others are written in one language but use the script of another. A Latin message carved in Greek letters, for example, could signal the writer’s limited literacy, their cultural background, or the expectations of the intended audience. Script itself carried meaning. Seeing unfamiliar letters was enough to mark difference, even for those who could not read them.

Names provide another window into this world. Individuals often bore names that could function in more than one language, or names adapted to different contexts. A person might be known one way at home and another in official settings. These choices were not accidental. They allowed people to move between communities without fully surrendering one identity to another.

What all these cases show is that language in the Roman Empire was situational. People adjusted how they wrote and what they displayed depending on who they were addressing. Multilingualism was not a temporary stage on the way to uniformity. It was a stable condition, sustained over generations, and embedded in daily life.

Language did not merely transmit information. It signalled belonging, difference, memory, and power. In a world where people moved constantly and communities overlapped, speaking—or carving—more than one language was not a complication. It was a solution. (“Multilingualism in the Graeco-Roman worlds” Edited by Alex Mullen and Patrick James)

When Writing No Longer Matched Speech

For much of Roman history, people did not experience a sharp divide between what they spoke and what they wrote. Speech changed gradually, as all spoken language does, while spelling remained largely fixed. As a result, the written forms of Latin increasingly failed to reflect everyday pronunciation—but this was not seen as a problem. Writing was a learned skill, governed by convention, not a mirror of speech.

This gap between speech and writing widened over time. Words were pronounced differently in different regions, yet continued to be written according to inherited norms. Someone who spelled carefully was not necessarily speaking in an old-fashioned way; they were simply following the only accepted method of writing. Accuracy on the page reveals nothing certain about how a person sounded in conversation.

For a long time, people did not think in terms of “Latin” versus “Romance” as separate languages. Instead, they navigated different registers of the same linguistic world. Formal writing followed traditional models; informal writing, when it survived at all, often departed from them. Graffiti, private notes, and practical documents show spelling that bends toward speech, while official texts remain conservative.

This flexibility was widely understood. When accuracy and authority mattered, traditional spelling was used. When clarity and immediacy mattered—especially for material intended to be read aloud—writers were willing to relax those norms. The goal was intelligibility, not correctness.

Only much later did people begin to think of these differences as evidence of separate languages. That shift required not just changes in speech, but the establishment of competing writing systems, each taught and learned separately. Before that moment, variation was experienced as a matter of style, audience, and purpose—not as a boundary between languages. (“Speaking, reading and writing late Latin and early Romance” by Roger Wright)

Latin and Greek as Languages of Power

By the early Empire, language use was no longer a simple matter of conquest. Latin functioned as the language of Roman authority, law, and administration, but it was not enforced with rigid uniformity. In practice, Roman officials adapted to local realities. In the eastern provinces, Greek remained deeply entrenched, and Rome recognized that attempting to replace it would be impractical. As a result, Greek was effectively accepted as a parallel administrative language in the East.

Official announcements were often issued in both Latin and Greek. Legal texts, proclamations, and correspondence circulated in bilingual form, with Greek versions produced by Roman clerks rather than local translators. These translations closely mirrored Latin phrasing, reflecting Roman priorities rather than Greek literary style. The goal was clarity and control, not cultural accommodation.

At the same time, Latin retained symbolic weight. Even where Greek was dominant, Roman authority continued to present itself through Latin formulas, especially in legal and military contexts. The language of power was visible even when it was not widely spoken.

Where Latin Was Required—and Where It Was Not

Latin knowledge was not a universal requirement for Roman citizenship. Entire communities could be enfranchised without any expectation of linguistic assimilation. However, practical limits quickly emerged. Certain rights and activities—writing wills, engaging in litigation, holding office, or entering imperial service—required competence in Latin because Roman law operated exclusively in that language.

This created a clear distinction between formal status and functional participation. One could be Roman without speaking Latin, but advancement within the imperial system increasingly depended on it. Latin became indispensable not because it was imposed, but because it was unavoidable in key areas of public life.

In the East, this tension remained unresolved. Greek continued to dominate urban culture, education, and everyday communication. Latin appeared mainly in administrative islands: the army, imperial courts, and certain legal institutions. Outside those spaces, it rarely displaced local speech.

The Limits of Latinization in the East

Unlike the western provinces, the eastern Mediterranean was never fully Latinized. Greek already functioned as a shared language across vast regions long before Roman rule, supported by cities, schools, libraries, and literary traditions. Roman conquest did not dismantle this system. Instead, it largely operated alongside it.

In Egypt, Greek retained official status for centuries after Roman annexation, while the native Egyptian language continued among the rural population. Latin entered the region late and never replaced either language in daily use. Similar patterns appeared elsewhere in the East: Latin existed, but mostly at the margins.

Even Roman colonists sent eastward often became culturally Hellenized rather than spreading Latin to surrounding populations. Trade hubs, ports, and mixed cities remained Greek-speaking environments, with Latin confined to specific institutional roles.

Religion did little to change this balance. Early Christianity in the East operated primarily in Greek, and only later did Latin gain prominence in religious contexts—and mainly in the West.

A Divided Empire of Languages

Over time, the Roman world settled into a linguistic division that reflected its geography. The western provinces became increasingly Latin-speaking, eventually producing the Romance languages. The eastern provinces remained predominantly Greek-speaking, despite centuries of Roman rule.

This was not the result of failure, but of accommodation. Roman governance proved flexible enough to function without linguistic uniformity. Authority did not depend on erasing local languages, but on ensuring that Roman systems—law, taxation, military command—could operate where needed.

By late antiquity, even the imperial capital reflected this division. Latin remained the language of the army and formal administration long after Greek became dominant in daily life. Attempts to maintain Latin as a living urban language in the East ultimately faltered, not through resistance, but through demographic and cultural realities.

The Roman Language Balance

The Roman Empire did not impose a single spoken language across its territories. Instead, it developed a layered linguistic system: Latin for law and power, Greek for culture and communication in the East, and countless local languages beneath them. This balance allowed Rome to govern vast and diverse populations without demanding uniform speech.

In the end, neither Latin nor Greek achieved total dominance across the empire. Each prevailed in different regions, for different purposes, and among different communities. The Roman world was not monolingual—it was multilingual by design, sustained by pragmatism rather than ideology. (“The Conflict of Languages in the Roman World” by Robert J. Bonner)

Rome never required its subjects to sound the same. Authority functioned through law, habit, and accommodation rather than linguistic uniformity. What held the empire together was not a shared tongue, but a shared ability to make oneself understood.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: