Antinous and Hadrian: Love, Devotion, or Divine Ambition?

In the shadowy chronicles of Roman history, there is a relationship that have sparked intrigue and questions; that between Emperor Hadrian and the enigmatic Antinous.

Was the bond between Hadrian and Antinous a story of forbidden love, a calculated act of imperial propaganda, or something far more elusive? The young Greek from Bithynia, whose beauty captivated the most powerful man in the empire, met a tragic and mysterious end, leaving behind a legacy shrouded in speculation.

Why did Hadrian deify this youth, elevating him to the status of a god? And what secrets lie behind the waters of the Nile, where Antinous’ life came to an abrupt end? These questions have echoed through the centuries, challenging historians and romantics alike to uncover the truth.

A Face that Defined Imperial Ideology

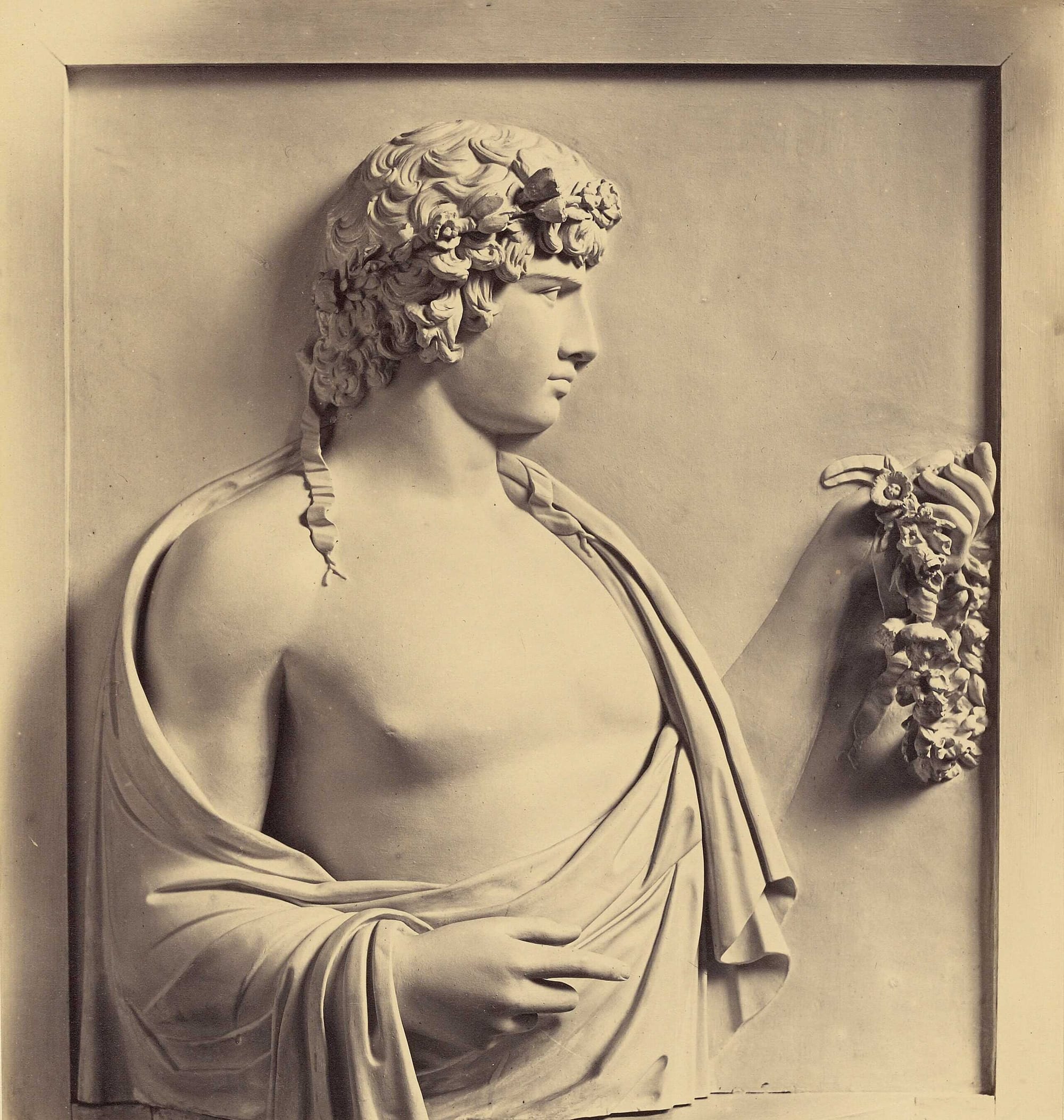

One of the most recognizable figures from antiquity is the youthful Greek, whose image, immortalized nearly two thousand years ago, remains widely known today. His statues depict him as a contemplative figure with downcast eyes, soft facial features, heavy curls framing his face, and a body that approaches the idealized heroic nude, though softened by his youthful form.

Over 90 statues of Antinous have been identified, portraying him consistently as Emperor Hadrian’s beloved. Despite his death at a young age, his image has persisted, taking on new meanings across time. Following his death, Antinous was deified, and his portraits were central to a cult that spread across the Roman Empire.

His worship waned with the rise of Christianity but reemerged in the Renaissance, when his likeness inspired admiration and new works of art.

A bas relief of Antinous in Villa Albani, by Robert Macpherson. Credits: J. Paul Getty Museum, Public domain

By the 18th century, Antinous became a symbol of homosexual desire, referenced in the writings of figures such as Oscar Wilde and Victor Hugo. Today, his image continues to captivate scholars and viewers, with statues scattered in museums worldwide, from Rome and London to Washington and Toronto.

His portraits often drew on classical Greek sculpture, blending Polykleitan contrapposto and Praxitelean elegance with distinctive elements that marked them as uniquely "Antinoan." These statues were likely informed by Hadrian’s philhellenism, reflecting his affinity for Greek culture and his personal affection for the youth.

However, recent scholarship questions whether Hadrian’s cultural preferences were the sole influence on Antinous’ image. Since his portraits were produced posthumously, under Hadrian’s direction, they may have served a broader ideological purpose within the emperor’s policies. This interpretation ties his image to Hadrianic imperial ideology, raising questions about the role he played in the emperor’s political and cultural strategies.

Exploring these connections, we will seek to understand them as both a reflection of Hadrian’s affections and a tool of imperial messaging. Through a detailed analysis of the statues, Hadrian’s own image, and the ideological undercurrents of the period, we will try to uncover the deeper significance of Antinous within the context of Roman imperial power.

The Enigmatic Favorite of Hadrian and his Lasting Legacy

Antinous, the young Greek from Bithynium, is one of antiquity’s most mysterious figures. His life is scarcely documented, with ancient sources primarily focusing on his death and the profound impact it had on Emperor Hadrian. This lack of comprehensive records has left historians to piece together his story from fragmented references, statues, and speculative accounts.

His first known mention comes from Pausanias, a contemporary of Antinous. Pausanias describes a temple in Mantinea dedicated to the youth and notes his deification and connection to Hadrian, identifying his birthplace as Bithynium. The Emperor first encountered the young man in Bithynia, on the southern coast of the Black Sea, during his extensive travels in the eastern Mediterranean. However, only minimal details are provided, mentioning Antinous in passing as part of his description of Mantinea.

Cassius Dio offers slightly more information but focuses on the mysterious circumstances of Antinous’ death. Dio proposes two possibilities: an accidental drowning in the Nile or a voluntary human sacrifice for a ritual intended to prolong Hadrian’s life. Dio suggests that Hadrian spread the narrative of an accident to obscure the sacrificial ritual. However, Dio’s account, written decades after the events, likely reflects rumors that circulated among Hadrian’s political detractors.

“[He] honored Antinous, either because of his love for him or because the youth had voluntarily undertaken to die (it being necessary that a life should be surrendered freely for the accomplishment of the ends Hadrian had in view), by building a city on the spot where he had suffered his fate and naming it after him; and he also set up statues, or rather sacred images of him, practically all over the world.

Finally, he declared that he had seen a star which he took to be that of Antinous, and gladly leant an ear to the fictitious tales woven by his associates to the effect that the star had really come into being from the spirit of Antinous and had then appeared for the first time.”

Aurelius Victor, expands on Dio’s sacrificial theory, alleging that Antinous willingly gave his life at the emperor’s request, motivated by Hadrian’s poor health and belief in divination. Victor also condemns Hadrian for his “unnatural” passion for the young Greek, suggesting that their relationship drove an extravagant commemoration of the youth after his death.

The Historia Augusta briefly mentions Antinous in the context of Hadrian’s Egyptian travels. It reiterates the claim of voluntary sacrifice and notes the establishment of all the cult and oracles surrounding him, which it alleges were manipulated by Hadrian for political purposes.

Antinous died in October 130 CE, likely in his late teens or early twenties. Hadrian immediately founded the city of Antinoopolis on the Nile near the site of his death, initiated a hero cult in his honor, and commissioned a vast number of portraits. These actions immortalized his figure, transforming him into a symbol of divine beauty and devotion.

Antinous’ image is preserved in over 90 statues, making him one of the most frequently depicted figures from antiquity, surpassed only by Augustus and Hadrian. These portraits depict him as a youthful, soft-featured figure, often associated with classical Greek ideals of beauty. Some statues incorporate elements of deities like Apollo, Dionysus, and Hermes, reflecting Hadrian’s philhellenism and possibly aligning Antinous with divine qualities.

While these representations idealized him, they offer little insight into his personality or role at court. Scholars have debated whether the statues capture a passive, melancholic figure or an active and loyal companion. Despite this ambiguity, his physical beauty and mysterious aura have made him an enduring icon.

Beyond the ancient sources, modern scholarship and fiction have attempted to fill in the gaps of his life. Speculations include theories about his entry into Hadrian’s entourage, his possible education in the Palatine Schools, and the nature of his relationship with the emperor—ranging from father-son dynamics to a romantic or sexual connection. Antinous’ death generated considerable attention, primarily due to Hadrian’s extraordinary grief and efforts to memorialize him.

The cult of Antinous persisted for two centuries, and his statues remain scattered across museums worldwide, continuing to captivate viewers and scholars alike. The sources emphasize Hadrian’s response to his death rather than his life, framing him as a reflection of the Emperor’s affections and imperial policies.

However, this limited focus leaves many questions unanswered:

What drew Hadrian to Antinous? How was their relationship perceived by the court? And what might Antinous’ life have revealed about the culture and politics of Hadrian’s reign?

Thus, Antinous remains a figure shrouded in mystery, his life eclipsed by the legacy forged in his death. While the surviving sources focus on Hadrian’s grief and commemoration, they offer only glimpses into the young man’s life and character. As Alfred Lord Tennyson once remarked, “If we knew what Antinous knew, we would understand the ancient world.” Without further discoveries, the enigmatic youth is left to us as an immortalized ideal—a symbol of beauty, devotion, and the enduring power of imperial commemoration. (The Image of Antinous and Imperial Ideology, by James Fleming)

Antinous Through the Ages: From Imperial Icon to Modern Myth

Cassius Dio’s account highlights the interplay between fact and fiction in the narratives about Antinous, reflecting ambiguity in Hadrian’s emotions and motivations. Dio connects the proliferation of statues commemorating him to his death, describing them as both likenesses (andriantes) of the deceased and objects of worship (agalma). The statues, central to a new cult dedicated to Antinous, became a target of early Christian criticism, but they also served as a foundation for later writers’ admiration of his beauty and explorations of his character.

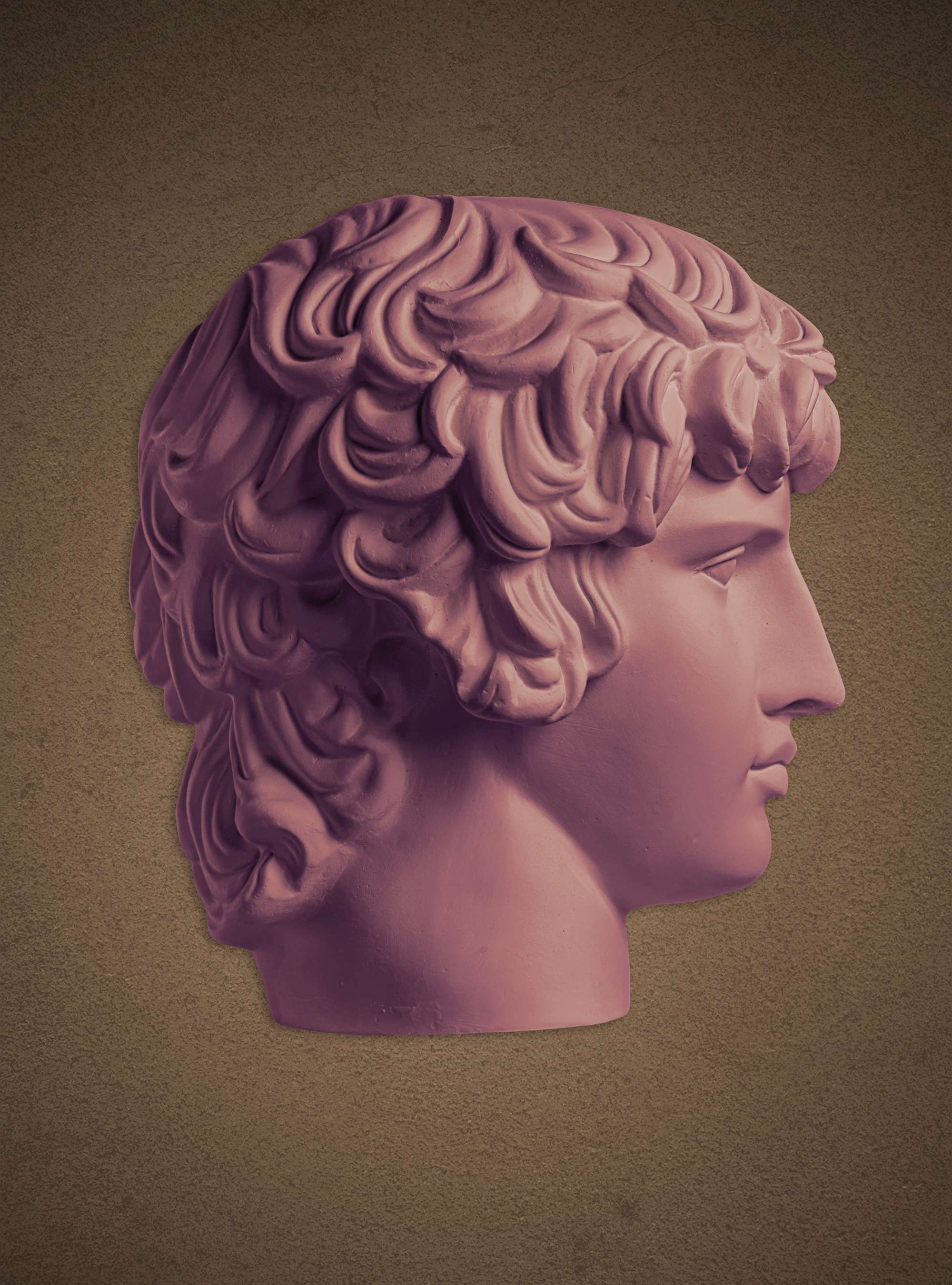

The late 19th century saw Antinous surpass Ganymede as the primary classical icon of male beauty, particularly in the context of emerging gay identities. His physical form, as captured in statues, became a focal point for scholarly essays and art historical catalogues, which emphasized his sculpted representations as central to understanding his legacy. These works solidified his status as a cultural figure, inspiring literary and academic productions in the early 20th century.

Victorian-era studies often depicted the teenage man as an enigmatic figure—his statues admired yet symbolically unattainable. Contemporary interpretations have been significantly influenced by Marguerite Yourcenar’s Memoirs of Hadrian, where Antinous is characterized as a reflective and self-absorbed youth. Yourcenar’s portrayal draws on surviving statues to present him as embodying multiple divine roles through his various postures and activities, contributing to his enduring legacy as a subject of fascination.

“The youth half reclining on a couch, knees upraised, was that same Hermes untying his sandals; it was Bacchus who gathered grapes or tasted for me the cup of red wine; the fingers hardened by the bowstring were those of Eros. “(Yourcenar 1954, 176–7)

Her portrayal also brings the youth to life not only in Hadrian’s memory but through the numerous sculptures that adorned Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli, as well. She highlights the emperor’s desire to immortalize his companion’s beauty in marble, noting that the resulting statues, with “that dangerous countenance and its elusive smile,” held a captivating power over viewers.

This sculpted Antinous became central to gay history and imagination, representing more than just the historical figure or Hadrian’s commemorative efforts.

Antinous is nowadays also celebrated as an LGBTIQ+ icon. Credits: Stanislav Chegleev from Getty Images, by Canva

As a replicated image from the start, this symbolism extends far beyond his brief life and Hadrian’s homage. Both ancient portraits and modern restorations of Antinous have inspired writers, poets, and historians to depict him as an enigmatic and layered figure. Nineteenth-century interpretations, influenced by Victorian attitudes toward sexuality, imbued him with a complex identity—marked by a strong will, mystery, and an overtly sexualized presence.

In this period, when the modern notion of homosexuality was taking shape, Antinous’ statues were often seen as enduring witnesses to and provocateurs of same-sex desire. His pensive expression and striking physique have been read as revealing not only his character and temperament but also his moral qualities, often framed through his association with homosexuality.

The history of these sculptures, shaped by both ancient and contemporary interpretations, influences how viewers engage with them today. Yet, as with many antiquities, the line between factual history and artistic contrivance becomes blurred, with modern receptions blending personal memoir, fiction, and historical reimagining.

Victorian Antinous: Restored Statues and Reimagined Narratives

Victorian interpretations of Antinous often relied on ancient statues that had undergone significant restorations in earlier centuries, blending historical fact with imaginative reconstructions. Lorentz Dietrichson was the first scholar to conduct a comprehensive review his many images, critiquing the extensive and often speculative restorations applied to them.

For instance, the statue depicting him as Hercules in the Louvre features a portrait head combined with an unrelated body, a pairing created through restoration. Similarly, the Antinous as Ganymede statue in Liverpool’s Lady Lever Gallery was identified as such in the 18th century due to the figure’s jug and cup—key attributes that are now known to be 18th-century additions.

Another example is a statue of him holding a "water plant," which seemingly ties his historical death by drowning to the myth of Hylas, the young Argonaut seized by water nymphs. However, Dietrichson noted that the statue’s head and both arms—the essential elements linking it to Hylas—were 19th-century restorations.

Image Credits

#1: A bust of Antinous as Osiris, Yannick Béra, by Canva

#2: Egyptian Influence in Striding Statue of Antinous, cascoly, by Canva

#3: A bust of Antinous Mandragone, Marcio Skull, by Canva

#4: A statue of Antinous, Mathew Browne, by Canva

#5: Bust of Antinous from Rome, Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 4.0

#6: A Thracian marble portrait bust of Antinous, from Patras, Peloponnese, Rawpixel, Public domain

These examples illustrate how contemporary artistic agendas influenced both the physical reconstruction of the statues and the scholarly interpretations of their iconography, often reflecting Victorian desires and anxieties. In Victorian poetry and scholarship, the young Greek is rarely depicted as a solitary figure. Instead, he is consistently represented in relation to others: his supposed sculptor, an admirer, or an enthralled viewer.

Those narratives often portray these artist-viewers as stand-ins for Hadrian, whose artistic vision is believed to underpin the beauty of Antinous as preserved in marble. Across a spectrum of writing, from academic studies to imaginative reinterpretations, these representations reflect a shared response to his compelling presence, further entangling historical authenticity with Victorian interpretations.

Antinous and Dorian Gray: The Timeless Face of Seduction

The modern moniker “face of the antique” for Antinous resonates with Oscar Wilde’s depiction of the Bithynian youth as a counterpart to Dorian Gray in The Picture of Dorian Gray. Basil Hallward, the artist who creates the novel’s infamous portrait, draws a parallel between the young man and Dorian, stating: “What the invention of oil-painting was to the Venetians, the face of Antinous was to late Greek sculpture, and the face of Dorian Gray will some day be to me”.

This comparison emphasizes his role as a transformative inspiration in art, likened to a breakthrough technique. However, Wilde imbues this admiration with a sense of danger, as Hallward describes his first encounter with Dorian Gray:

“I had come face to face with someone whose mere personality was so fascinating that, if I allowed it to do so, it would absorb my whole nature, my whole soul, my very art itself.”

Similarly, Wilde’s vision suggests a personality capable of overwhelming others through its sheer physical presence, requiring no dialogue to assert its power. Wilde further extends the parallel by casting Dorian Gray in various mythological roles, including Antinous, as Hallward poses him as a range of classical heroes and deities. Through this layering of identities, He cements Hadrian’s favorite as an enduring symbol of physical beauty and irresistible allure, whose legacy continues to inspire and haunt artistic imagination.

Wilde’s portrayal of Antinous places him among mythical male figures such as Paris, Adonis, and Narcissus—effeminate and aestheticized beauties that challenge conventional notions of masculinity.

Photo of Oscar Wilde, the Irish literary genuis, in flamboyant costume. Credits: The Everett Collection, by Canva

Wilde emphasizes his vanity and allure, tying physical beauty to themes of seduction, death, and an enduring afterlife. These elements are reflected in the aforementioned Victorian interpretations, which often associated his "divine" beauty with danger and anxiety, blending admiration with unease.

Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, a pioneer in documenting same-sex love, highlighted Antinous as a unique icon of ancient homoeroticism. Through poetic narratives and essays, Ulrichs dramatized the young man’s death, imagining him as a figure entwined with myth and celestial phenomena, such as the appearance of a star at his death. Ulrichs even created an alabaster carving, to bring this symbolic figure closer to his personal life.

John Addington Symonds, another prominent Victorian figure, emphasized the realism of all the existing sculpted representations, portraying him not as a mythic figure but as a tangible individual. Symonds, like others of his time, interpreted the statues as embodying Antinous’ melancholy and enigmatic personality, suggesting that his somber mood was intrinsic to the sculptures themselves.

By the late 19th century, his image had been firmly established as an icon of both antiquity and homoeroticism, his beauty serving as a bridge between historical reality and mythic imagination. His statues became symbols of longing and reflection, inspiring both art and scholarship with their blend of allure, melancholy, and an air of danger.

Moreover, the Victorian interpretations we mentioned often linked the melancholy seen in his statues to narratives of his tragic death, commonly viewed as a suicide to escape the constraints of being Hadrian’s beloved. These interpretations reflected Victorian anxieties about homosexuality and contributed to emerging notions of same-sex identity.

Scholars and writers of the period emphasized on his physical beauty, combining his statues’ grace and posture with themes of vanity and tragedy. Those statues were interpreted as embodying both his personality and his role as an icon of homoeroticism. Even fragmented sculptures, such as torsos without heads, were identified through their distinctive posture and form.

The Capitoline Antinous and other works exemplified how his body became central to his identity in art. These representations tied him to broader Victorian concerns about effeminacy and non-normative gender roles, while also attracting admiration and desire from scholars and viewers. (Sculpting Antinous, by Bryan E. Burns)

The Enigma of Rome’s Immortal Youth

Antinous remains one of ancient Rome’s enduring mysteries. A young man from an obscure provincial town rose to become the favorite of Emperor Hadrian, a man three times his age. Antinous’ proximity to Hadrian allowed him to accompany the emperor on his travels across the empire and, ultimately, to claim Hadrian’s heart when he died in the Nile. Despite this, almost nothing substantive is known about him, and the extraordinary legacy he left behind stands in stark contrast to his humble beginnings.

Hadrian’s profound grief for Antinous and the extensive commemoration efforts that followed, truly set him apart. These actions elevated an otherwise anonymous figure into a lasting symbol, yet this young man remains a paradox: simultaneously well-known and unknown.

Who Antinous was in life is lost to history, leaving only speculation.

Hadrian had eight years to promote Antinous’ afterlife before his own death in 138 CE. The result was a legacy that persisted for two centuries. But was this commemoration purely an act of personal devotion, or was it also politically motivated? Hadrian may have used his memory not only to immortalize his beloved, but also to further his own ideological and political goals.

Also central to this discussion, is Hadrian’s philhellenism. Was the creation of Antinous’ enduring image simply an expression of Hadrian’s admiration for Greek culture, or did it serve a deeper purpose?

To explore this, one must examine Hadrian’s policies and ideology, tracing how the young Greek fit into the emperor’s broader vision. If Antinous’ legacy was more than just an extraordinary act of commemoration, it may have been aligned with Hadrian’s political or cultural agenda, reflecting not only his affection for him, but also his strategic use of imagery within Roman imperial ideology.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: