Aelian: The Roman Who Wrote in Greek

Aelian, the Roman who wrote in Greek, turned away from the noise of empire to preserve its memory in prose. His Varia Historia and On the Nature of Animals gather fragments of wisdom and wonder, binding moral reflection to the art of remembrance.

In an empire where Latin ruled law and power, Claudius Aelianus chose another tongue. Born in Praeneste around 170 CE, Aelian lived under the high tide of Roman order yet wrote in the language of Plato. His Greek flowed so pure, contemporaries called him “the honey-tongued” — meliglossos.

From his pen came not the rhetoric of conquest but a treasury of wonder: animals that reason, cities that reveal their customs, and men who, through their deeds, expose the nature of virtue and folly. His world was one of moral parable and observation, where curiosity became philosophy and the natural world a mirror of the human soul.

Claudius Aelianus and the Art of Memory

Aelian was an early third-century Roman who swore he never left Italy, wrote Greek with Attic purity and a sweet, flowing style that earned him a reputation as a native voice. What survives—twenty rustic letters, On the Nature of Animals (De natura animalium), the unfinished Varia Historia, and scattered fragments—belongs to the imperial revival of Greek eloquence.

He avoids systems and novelties; instead, he curates Greece in pieces. The fragment is his favored unit: brief, vivid, recombinable notes that preserve and re-animate classical memory for a post-classical world. In the Nature of Animals epilogue he even asks to be counted among poets, natural philosophers, and historians—staking a claim that remembering is itself an art.

Memory is the thread that binds his pages. On the surface he praises beasts gifted with remembrance; beneath, he probes how cultures remember—by nature (phusis) or by art (tekhnē). Hoopoes haunt wastelands and smear their nests, behavior read through mythic recall; they:

“seem to have a recollection of their formerly human qualities… and a hatred for the race of women” (δοκοῦσι… ἐν μνήμῃ… μίσει τοῦ γένους τοῦ τῶν γυναικῶν,

A bull:

“will never forget” a blow (οὐκ ἂν ποτε λήθην λάβοι,);

under the yoke

“he is like a prisoner and is tranquil” (ἔοικε δεσμώτῃ καὶ ἡσυχάζει),

yet once freed he exacts justice. The Indian elephant, once shackled,

“longs for freedom and becomes murderous… and does not endure to be a slave and a prisoner” (τὴν ἐλευθερίαν ποθῶν φονᾷ… δοῦλος εἶναι καὶ δεσμώτης οὐκ ὑπομένει).

Other creatures shame us with piety:

“Dolphins are mindful of their dead” (δελφῖνες… νεκρῶν μνήμονες),

lifting corpses for burial and trusting just, music-loving men (οἱ ἀπὸ Μουσῶν καὶ Χαρίτων) to honor them; Aelian counters with human scandals—distinguished dead refused burial—and laments those who:

“have forgotten themselves” (σφᾶς αὐτοὺς λελήθασι).

Eagles keep vigil like lovers; in one tale, when “the boy” dies, the eagle

“threw himself upon the pyre” (ἑαυτὸν εἰς τὴν πυρὰν ἐνέβαλεν,).

Lions remember benefaction:

“that memory is a constant attribute even of animals” (Μνήμην… παρακολουθεῖν καὶ τοῖς ζῴοις),

proven by Androcles and the grateful lion.

From nursery to throne, remembrance underwrites virtue. The mare is praised because she can:

“remember the foal” (τοῦ πώλου… μεμνῆσθαι δεινή);

elephants guard their young with exemplary mindfulness. Set against them stands Laenilla, a Roman noblewoman who:

“placed lust before her own sons” (τὸν ἔρωτα ἐπίπροσθεν τῶν υἱέων ποιησαμένη).

For Aelian, τὸ μνημονεύειν—active, ethical remembering—supports philoteknia, dikē, charis, and sōphrosynē alike: it is the mental habit that holds Greco-Roman society together.

He distrusts artificial memory. Animals:

“have no need of the artifice pertaining to memory” (δεῖταί γε τέχνης τῆς ἐς τὴν μνήμην οὐ…, ).

He mocks mnemonic theater with the glowing kunospastos plant: men set markers (σημεῖα) at night because by day they “could not remember” (μνημονεῦσαι); a dog plucks the root and dies, buried with rites “when Helios sees the roots” — knowledge won against nature leaves guilt in its wake.

Law, too, is second to nature: elephants honor elders without statutes—

“how could Lycurgus compete with the laws of nature?” (ποῦ… τοῖς τῆς φύσεως νόμοις;).

Yet Aelian concedes the paradox: only writing can conserve this “natural” ethic. His book is a cabinet of remembrance that keeps pointing to its own stitches—

“as I noted above…” (ἀνωτέρω μνήμην ἐποιησάμην)—

playful proof that human memory rides on signs.

Under Severan skies—an age of erased portraits and chiselled names—this obsession reads like quiet resistance. Fraternal murders are avenged by a faithful serpent; a hoopoe’s crest becomes a “memorial” (μνημεῖον) of filial piety in exile. Even the catalog of animal voices (“roars, bellows, whinnies…”) hints at courtly circles that once delighted in such philology.

The result is not zoology but a moral anthology: fragments that remember—of beasts, of men, and of the fragile art that keeps both from being forgotten. ("Claudius Aelianus: Memory, Mnemonics, and Literature in the Age of Caracalla" by Steven D. Smith. In Greek Memories, Theories and Practices, edited by Luca Castagnoli and Paula Ceccarelli)

Between Fame and the Page

Claudius Aelianus was born in Praeneste, some 35 kilometers east of Rome, between 161 and 177 CE — during the reign of Marcus Aurelius and the youth of Commodus. By the time Septimius Severus celebrated his tenth anniversary as emperor in 202, Aelian was a mature man, and he lived through the violent transitions that followed: the deaths of Severus and Geta, the rise of Caracalla, and the eccentric reign of Elagabalus.

A student of the sophist Pausanias, who held the Roman chair of rhetoric in the late second century, Aelian became renowned for his mastery of Attic Greek — the refined literary language of his age.

A priest by office and a man of letters by vocation, he also composed two religious treatises (On Providence and On Manifestations of the Divine), a biting invective against Elagabalus titled Indictment of the Little Woman, and perhaps a series of epigrams once inscribed on hermai that adorned his villa garden.

All of his works were written in Greek. Though some once imagined him part of Julia Domna’s literary circle, evidence for any such salon is lacking. What is certain is that Aelian’s elegant compositions earned admiration in his lifetime and shaped learning across a millennium of the Roman and Byzantine worlds.

Among his writings, On the Nature of Animals stands as his masterpiece. Despite its title’s resemblance to Aristotle’s Historia animalium, Aelian’s approach is far from philosophical system. He was no natural scientist but a moralist and stylist, offering readers a treasury of stories — elephants that dance, asps that whisper to boys in dreams, monstrous octopuses haunting Italian shores. The pleasure of his prose draws the reader in; beneath its sweetness lies sharp moral reflection.

Aelian was disenchanted with the pretensions of his age, and his book becomes a mirror for the failures of human virtue. The work’s deliberate lack of order — no taxonomy, no linear argument — is itself a statement. Its seventeen books are arranged like scattered jewels, fragments that can be read in any order, forming a mosaic of thought rather than a system.

Each vignette stands as a finished miniature, polished and self-contained. There is no guiding voice explaining how one story leads to the next; the reader may wander freely, reading in sequence or at random, tracing meaning through association and contrast. This deliberate openness reflects the anthologizing taste of Aelian’s era — a culture that prized quotation, collection, and the display of learned fragments.

His anecdotes, gathered from myth and observation, were the perfect currency of paideia, the cultivated knowledge of the educated elite. Like the witty exchanges in contemporary romances and sophistic dialogues, Aelian’s narratives transformed animal lore into moral allegory and social critique.

For Aelian, such fragments formed a kind of intellectual treasure (keimelion), a storehouse of memory. Each story could be lifted, recombined, and reused — a mark of the virtuoso rhetorician who dazzled not by invention but by mastery of tradition. Yet beneath this apparent disorder runs an organizing current: a steady moral “I,” a narrative consciousness seeking pattern amid chaos. His voice moves through the tangle, invoking the divine power that unites nature’s mysteries.

This tension — between order and multiplicity, between the voice and the fragments — gives the Nature of Animals its peculiar vitality. Aelian’s self-conscious “I” emerges not as an imperial authority but as a composite presence, shaped by intersecting discourses of nature, morality, gender, kingship, and pleasure.

The author does not disappear behind his citations; he redefines authorship itself as the art of assembling knowledge, editing the voices of the past into new harmony. His book stands, as he himself did, between the statue and the library: between the public monument of reputation and the private archive of memory.

Turning away from public oratory, Aelian withdrew from the arena of palaces and acclaim to a quieter world of writing. In that retreat, he embraced what might be called a minor stance — a humility before the clamor of empire and an affinity with the creatures he described. He identifies with the irrational beasts of his pages: not a slave, as he proudly notes, but close to them in voice and sympathy.

He writes like them, borrowing their polyphony, their foreign tongues. His book becomes both garden and burrow — a field of blossoms and a network of tunnels undermining the grand architecture of imperial rhetoric.

Behind its conservative moral tone lies the possibility of transformation. The reader who enters Aelian’s labyrinth confronts questions of culture, divinity, gender, and power. His contemporaries may have seen in him a model of Roman virtue; yet his text imagines a different reader — one who will slip from the shadow of the statue into the living maze of the library, seeking metamorphosis in the act of reading. (Man and animal in Severan Rome. The literary imagination of Claudius Aelianus, by Steven D. Smith)

The Scholar and His Mosaic: Aelian and the Varia Historia

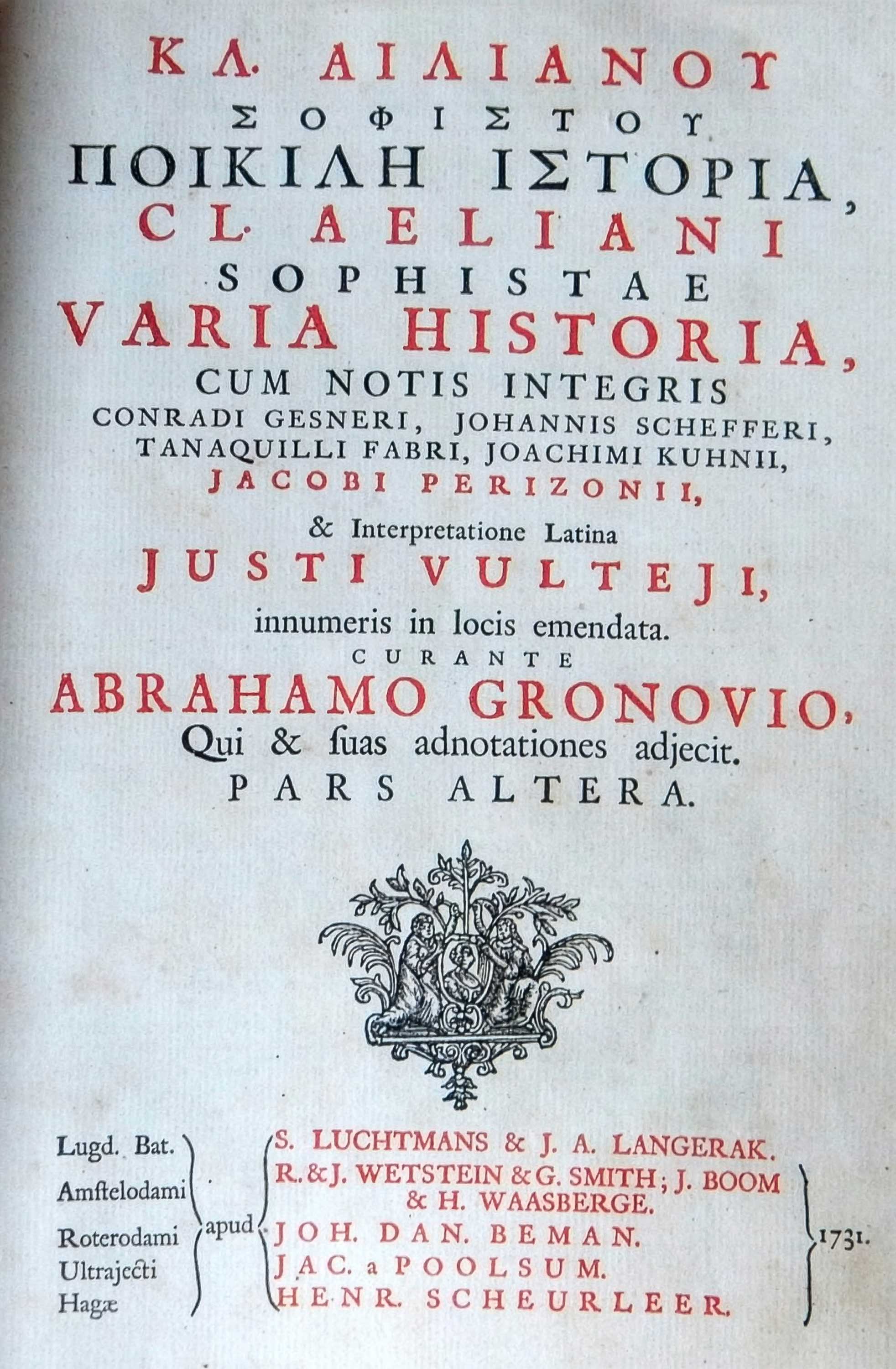

Among the works of Claudius Aelianus, the Varia Historia stands apart as a testament to the refined curiosity and literary artistry of its author. It is not a history in the conventional sense but a constellation of brief prose chapters — anecdotes, moral reflections, philosophical observations, and marvels of nature and humanity — all presented without systematic order.

Yet this deliberate disorder, far from careless, reveals Aelian’s purpose: to capture the variety of human experience and the accumulated wisdom of the Greek world as it survived into the Roman age.

The Varia Historia belongs to a long-standing tradition of miscellanies, but its texture and tone are uniquely Aelian’s. Each passage gleams with the polish of Attic prose, composed by a Roman who loved Greek as his native tongue. The work’s very lack of structure evokes a moral principle — that knowledge, like the world itself, resists neat classification.

From the behavior of kings and the follies of philosophers to stories of animals, temples, and omens, Aelian gathers fragments of the past and arranges them as one might arrange tesserae in a mosaic. Together they form an image of a cultured mind preserving what might otherwise be lost to time.

What defines the Varia Historia is not only its content but its attitude toward learning. Aelian writes as both custodian and critic of memory. He collects the sayings and deeds of earlier ages, yet his selection reflects judgment and irony. Through this assembly of fragments, he allows readers to glimpse the moral landscape of the Empire — a world where Greek wisdom met Roman power, and where a man’s education became a measure of virtue.

A Life Between Rome and Greece: The World of Claudius Aelianus

Claudius Aelianus belonged to an Italy still proud of its Latin traditions yet captivated by Greek culture. Educated under the sophist Pausanias, who taught rhetoric in Rome, Aelian mastered the Attic dialect so perfectly that he was celebrated as “the honey-tongued,” as aforementioned.

Though he never left Italy, his intellectual geography stretched from Athens to Alexandria. In his works, he called upon the entire Hellenic past, fusing it with Roman moral ideals to create a hybrid vision of civilization.

Aelian’s life, viewed through his writings, was that of a scholar-priest, a man of leisure and letters who turned away from public ambition. He was said to have held priestly office in Rome, but his true temple was the written word. His prose, musical and urbane, was steeped in the moral gravity of Greek tradition yet tinged with the realism of Roman society. The world he inhabited — that of the Severan court — was one of opulence and instability. Aelian’s voice, in contrast, was contemplative and measured.

He lived through the reigns of Septimius Severus, Caracalla, and Elagabalus, observing from a distance the excesses and moral fractures of imperial politics. His moral tone, shaped by the Stoic and Platonic schools, positioned him as a quiet dissenter against the turbulence of his age. While others sought prominence in the imperial palaces, Aelian sought permanence through literature.

His writings — from the Varia Historia and On the Nature of Animals to his lost invective against Elagabalus — reveal a mind at once nostalgic and defiant, convinced that Greek learning remained the truest measure of civilization.

A Living Text: The Transmission of the Varia Historia

The Varia Historia reached later generations through a complex and uneven manuscript tradition that mirrors the fragmentary spirit of the work itself. Copied and recopied throughout late antiquity and the Byzantine period, the text was valued less for its structure than for its inexhaustible store of stories — a treasury of quotations, moral examples, and curiosities ready for reuse. Each brief chapter could stand on its own, inviting readers to approach the collection as they might a cabinet of wonders.

The earliest manuscripts reveal the fascination the work inspired among scholars and moralists, who mined it for evidence of ancient customs and lost authors. When the first printed editions appeared in the Renaissance, humanists embraced Aelian as both a moralist and an antiquarian. His Varia Historia was read not as an exercise in philosophy but as a mirror of the ancient world’s mind — a text that preserved the voice of a man who revered Greek wisdom while living in the heart of Rome.

Even in its textual imperfections, the Varia Historia retains its peculiar charm. Its disorder is its design; its variety, its coherence. Through it, Aelian invites the reader to partake in the intellectual play of recollection — to wander among fragments that, though scattered, preserve the shape of a lost whole. It is a book of memory, not of method, and in that lies its enduring life. (Claudius Aelianus Varia Historia and the tradition of the miscellany, by Diane Luise Johnson)

Though centuries have passed since his “honey-tongued” prose delighted the Roman salons, Aelian’s voice still carries a quiet defiance. He reminds us that civilization endures not through monuments or conquest, but through the preservation of memory — in stories, fragments, and the written word.

His works, suspended between Rome and Greece, between the statue and the library, speak of a man who sought truth not in power, but in recollection. To read Aelian is to enter a world where the past is never lost, only waiting to be remembered anew.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: