The Zoninus Collar: The Iron Collar that Spoke for the Silenced

It was meant to silence, yet it speaks across centuries. The Zoninus Collar—an iron ring forged not for adornment but for domination—once gripped the neck of a runaway slave in ancient Rome.

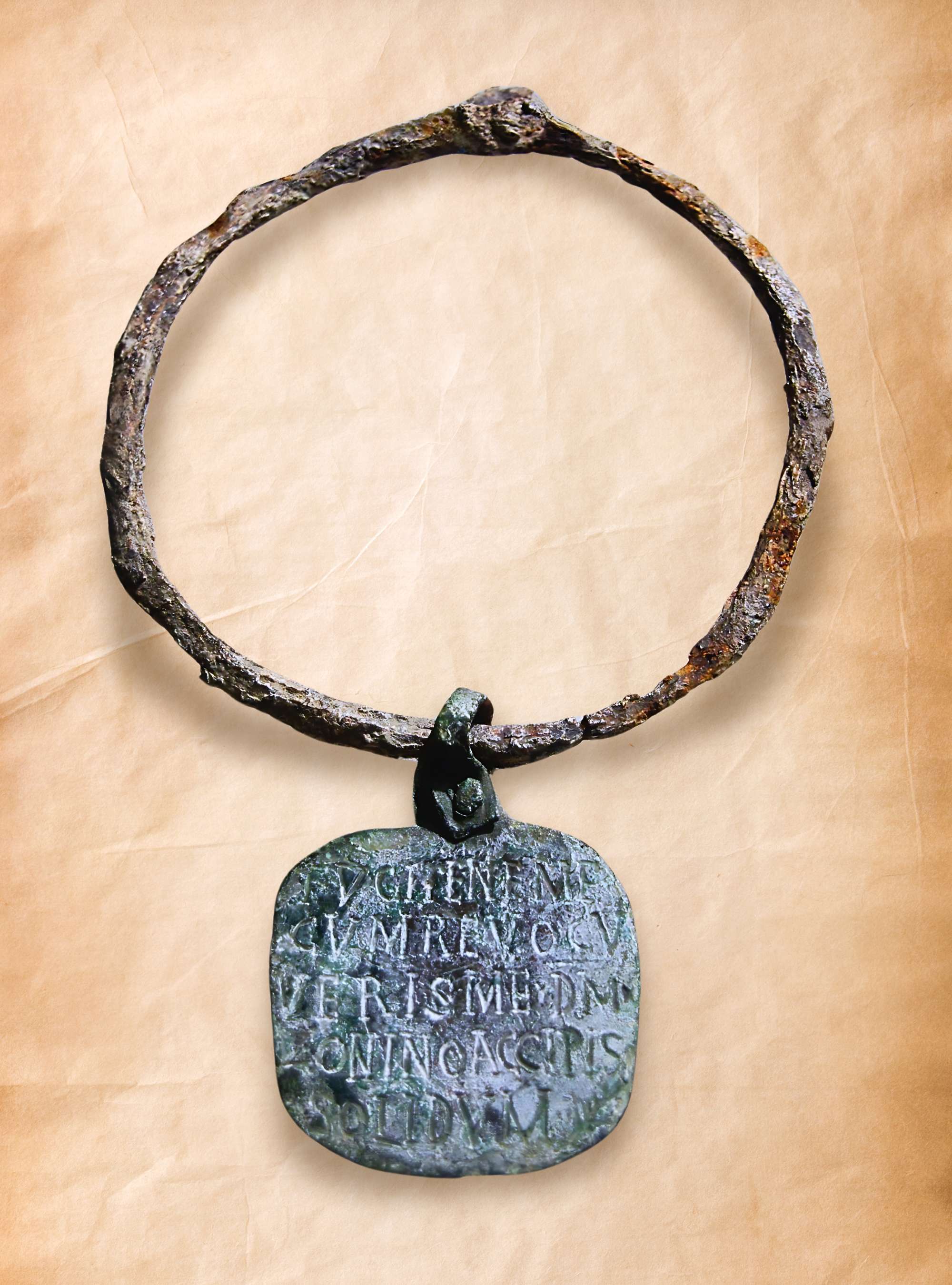

The Zoninus Collar is one of the most disturbing yet revealing artifacts of Roman slavery. Discovered in or near Rome and now held in a museum collection, it is an iron neck ring bearing a stark Latin inscription. These collars were used as a form of punishment, deterrent, and identification—branding the enslaved as both runaway and possession.

Held by Iron, Traced by History: Reading the Zoninus Collar

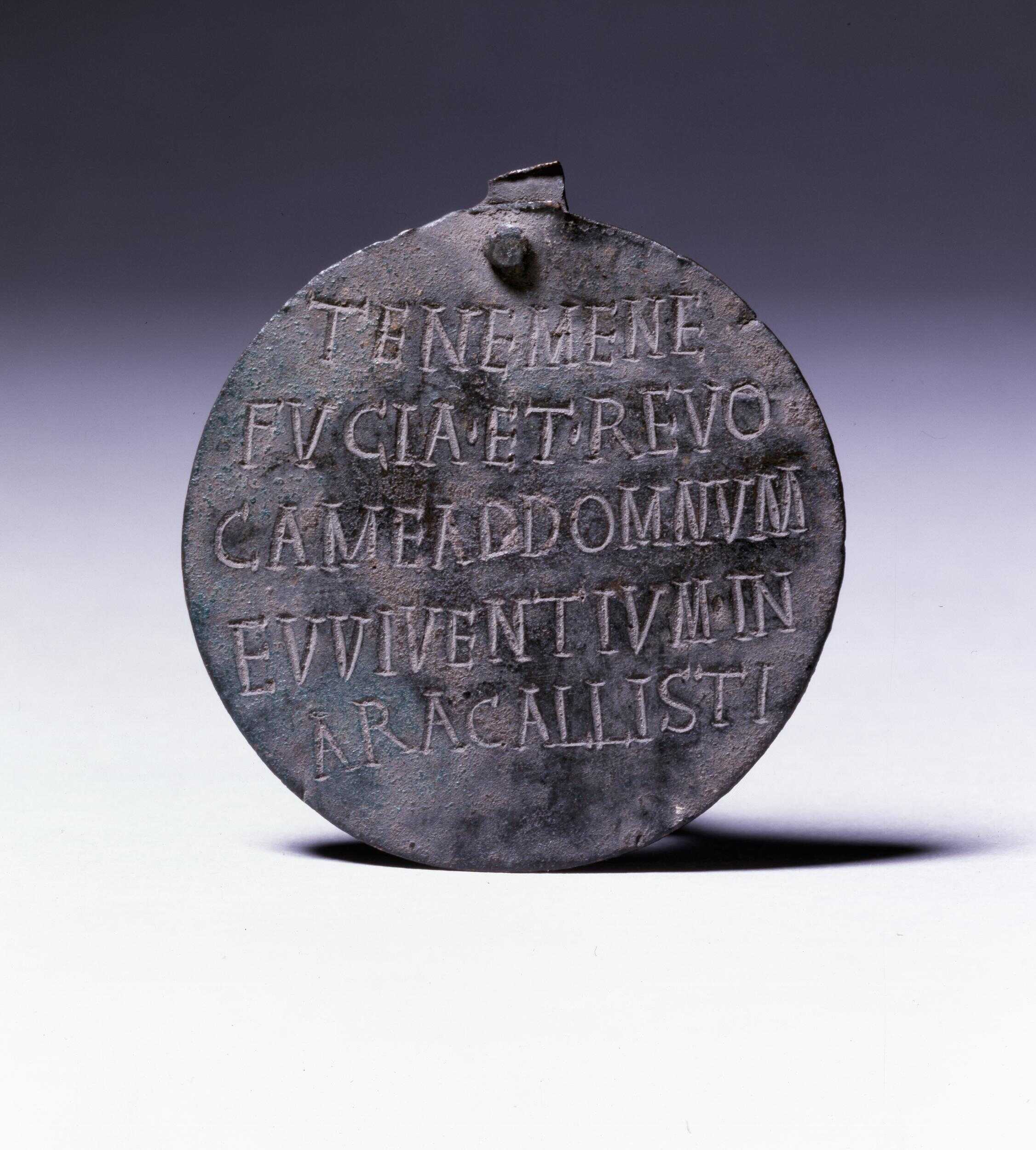

Housed at the Museo Nazionale Romano–Terme di Diocleziano in Rome, is a striking artifact: an iron slave collar with an attached bronze tag. The tag bears five lines of Latin inscription:

FVGITENEME

CVMREVOCV

VERISMEˇDMˇ

ZONINOACCIPIS

SOLIDVM

When expanded and punctuated, the message reads:

"Fugi, tene me. Cum revocaveris me domino meo Zonino, accipis solidum."

In English:

“I have run away; hold me. When you return me to my master Zoninus, you will receive a gold coin.”

The inscription ends with a carved palm frond. This collar is part of a known group—around 45 similar items survive today—used to identify enslaved people, particularly those who had tried to escape. Such inscriptions often instruct the finder to detain the wearer, name the owner, and sometimes include a return address.

Christian symbols like the Chi-Rho (XP) or a palm, as seen here, are also occasionally present. The Zoninus collar is exceptional in one detail: it offers a reward, a rare feature among these devices.

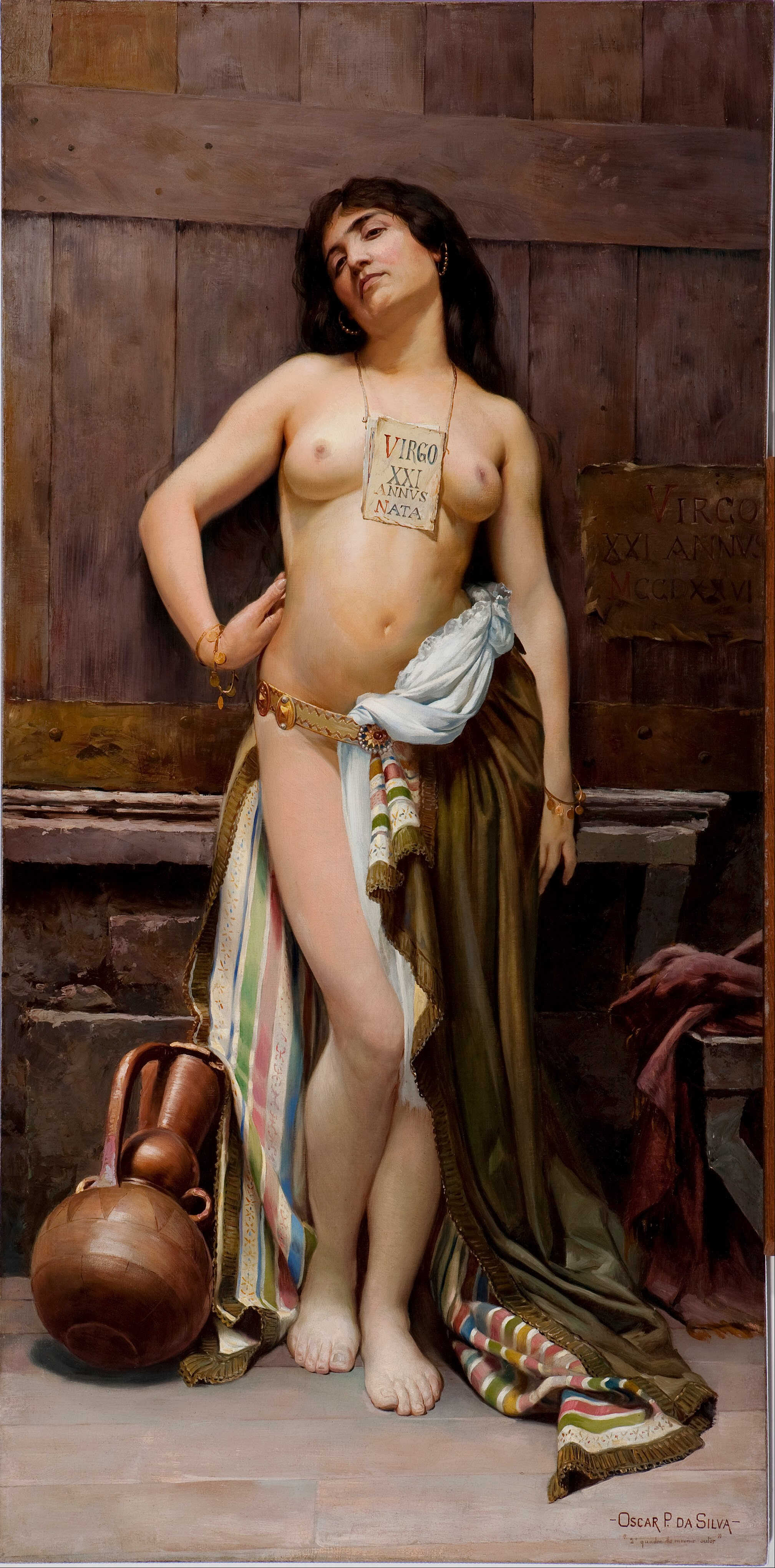

These collars weren’t standard issue for all enslaved individuals. Rather, scholars believe they were a punitive alternative to the more traditional Roman method of tattooing a runaway’s face. Wearing such a collar publicly marked the person as a fugitive, branding them both socially and physically.

I am the slave of my master Scholasticus, a respectable man; hold me lest I flee from the domus Pulverata

Credits: Dan Diffendale, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

As an object, the Zoninus collar stands out because it offers immediate, tangible proof of the realities of Roman slavery. It reveals how enslaved people were managed, controlled, and perceived—not merely as laborers, but as property subject to recovery.

Slavery formed the backbone of Roman society, and its influence is deeply embedded in the material remains of the era—from architecture to everyday tools. These items, shaped by the hands of enslaved laborers and by the ideologies of ownership, have the potential to shed light on the lived experiences of those in bondage.

Yet studying slavery through archaeology is fraught with challenges. Legal categories like “enslaved” are not easily detected in material remains. The archaeological record reflects the perspectives of elites far more than the marginalized, making physical traces of enslaved lives difficult to identify. Often, it’s unclear whether an object or space was specifically linked to slavery unless explicitly marked.

These interpretive problems are not limited to Rome—they mirror those faced in the study of slavery across cultures and time periods. However, new scholarly approaches are beginning to address these issues, combining comparative frameworks with innovative methodologies.

Still, a persistent challenge remains: the tendency to separate textual evidence from physical artifacts, a divide rooted in outdated academic traditions. This separation continues to influence how we understand the role of material culture in studying the institution of slavery.

From Artifact to Inscription: How the Antiquarians Reframed the Zoninus Collar

The Zoninus Collar first emerged in the historical record during the 18th century, featured in Museum Veronense, a 1749 publication by the antiquarian Francesco Scipione Maffei. Maffei, passionate about showcasing Verona’s ancient heritage, created a museum centered around inscriptions, and toward the end of his catalogue, he included items from other collections in the area.

The collar was listed among the possessions of marchese Alessandro Capponi, another aristocrat who shared Maffei’s deep interest in Greco-Roman antiquity. Only the Latin text of the collar was printed—there were no images, no physical description beyond it being “on a bronze collar,” and no discussion of where it was found or what it was used for.

The transcription followed the 18th-century norm: it kept the line breaks but introduced spaces between the words that weren’t present in the original. Some textual corrections were made, and decorative details like the palm frond were left out. The inscription was published alongside others from various object types—gravestones, a dedication to Mithras—treating them all as interchangeable texts rather than contextualized objects.

This treatment was typical of the antiquarian tradition, which began collecting and publishing Roman slave collars in the late 1500s. For centuries, these items were not viewed as evidence of slavery but simply as examples of Latin epigraphy, gathered for their textual value.

Collectors like Jacob Spon, a French physician and scholar, reflected this mindset in his 1679 work Miscellanea eruditae antiquitatis

A possible representation of Jacob Spon, based on historical sources. Credits: Roman Empire Times, OpenAI

He defined archaeology as the study of ancient remains, such as coins, inscriptions, and artifacts, and arranged his material typologically, including seven slave collars grouped with unrelated items like amulets and weights. While Spon noted which inscriptions he transcribed from objects and which from earlier publications, he showed no concern for their visual or physical form. His presentations ignored the actual layout of the texts on the objects, excluded symbols, and altered line breaks and lettering.

For these early collectors, the objects themselves had a social and intellectual function. They were shown to guests, gifted to peers, and displayed as signs of scholarly devotion.

Jean Mabillon, a French Benedictine and intellectual, recorded such moments in his travel diary Iter Italicum. During a 1685 visit to Naples, he documented a Roman slave collar and a coin of Procopius that he saw in a private collection. These encounters, steeped in personal exchange and intellectual curiosity, helped fuel the eventual publication and wider circulation of such artifacts.

But there was a contradiction in how these collars were treated. In private, they were tangible, handled and admired. In print, they were reduced to texts. Raffaello Fabretti’s 1699 catalogue of his own antiquities reflects this split: although he owned multiple slave collars, he only illustrated one—a circular tag with a hanging loop and five lines of text. The others were mentioned only as inscriptions, without drawings, contextual notes, or consideration of their meaning or use.

This approach has shaped how the Zoninus Collar and others have come down to us. On one hand, it is thanks to the efforts of these antiquarians that many of the known examples survive today. Of the more than 40 slave collars known to modern scholars, several were first recorded between the 16th and mid-19th centuries—seven of them in the 18th century alone, including Zoninus’.

Yet their collecting priorities had long-lasting effects. Items with inscriptions were far more likely to be preserved, while other associated finds—such as bones or burial goods—were often discarded.

This explains why many of the surviving slave tags have lost their iron collars, with the Zoninus Collar being a rare exception. Moreover, for the 24 collars and tags discovered before the late 1800s, no findspots or associated archaeological data have survived. While most are thought to have been found in Rome, no details confirm this.

Image #1: A copy of a Roman slave collar, by Antoine Mellies

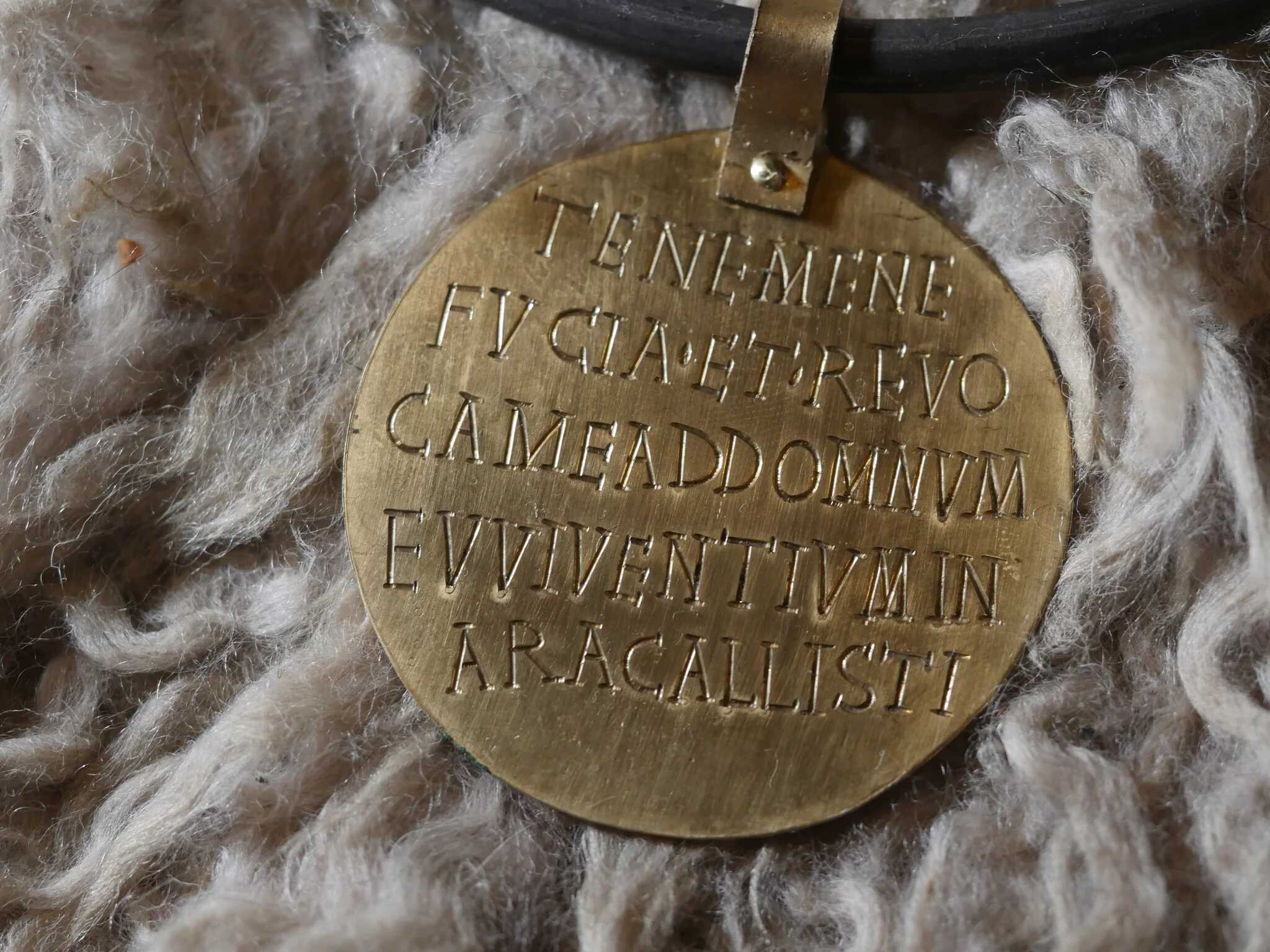

Image #2: A copy of the Zoninus Collar, by Tematika

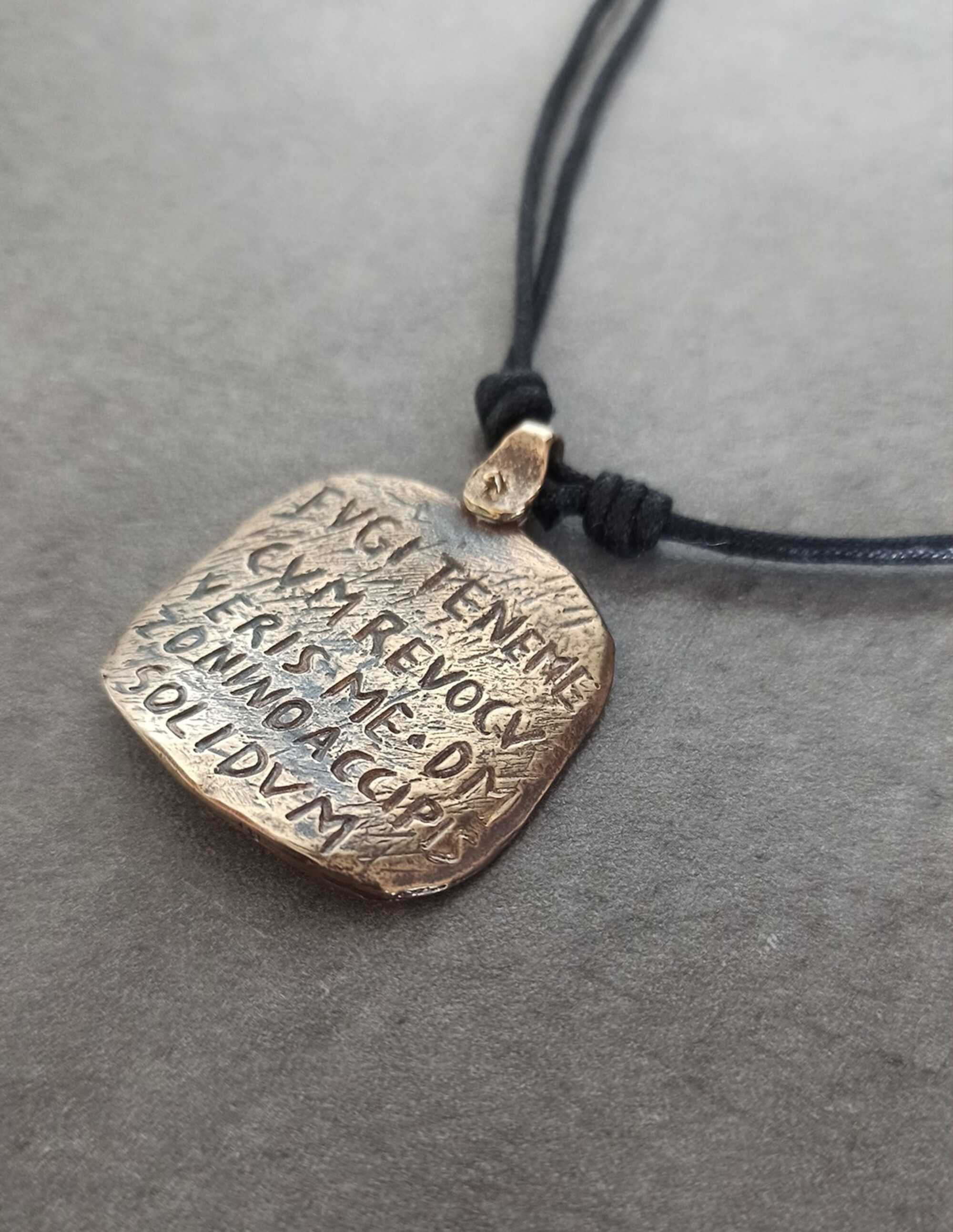

Image #3: A copy of a Roman slave collar, by Tematika

Although no serious doubts have been raised about the authenticity of the Zoninus Collar, the absence of excavation context leaves open the theoretical possibility of forgery—an issue that applies to other pieces from the same antiquarian pipeline.

The typological approach of early collectors, which grouped objects based solely on shared features, further removed them from their ancient environments and uses. In this way, Roman slave collars were transformed into isolated, decontextualized artifacts.

Today, the Zoninus Collar feels like a direct link to antiquity, seemingly offering raw, unfiltered access to the world of Roman slavery. But this impression is itself a legacy of 18th-century antiquarianism. The object, and even the idea of a “corpus” of Roman slave collars, owes as much to early modern collectors as it does to the ancient world.

From Latin Inscriptions to Lives in Chains: The Evolving Interpretation of the Zoninus Collar

The legacy of antiquarian scholarship still shapes how Roman slavery is understood today—often subtly and without recognition. The Zoninus Collar is a compelling example of this phenomenon.

After the death of Alessandro Capponi in 1746, his collection, including the collar, passed to the Museo Kircheriano in Rome, which had been established by Athanasius Kircher, a polymath of the 17th century. Even as late as the 19th century, catalogues from the museum continued to emphasize the inscription over the object itself, omitting any image of the collar.

Yet signs of a shift were emerging: the same catalogue provided measurements for the first time and speculated—incorrectly—that the collar might have been intended for an animal, as it appeared too small for a human neck. This entry reflected a transitional moment between antiquarian traditions and new 19th-century approaches to ancient material culture.

The Zoninus Collar remained in the Kircheriano collection until the newly unified Italian state took over in the late 1800s. The museum’s holdings were then redistributed according to modern principles of categorization: Etruscan artifacts went to the Museo Nazionale Etrusco, ethnographic material to the Museo Nazionale Preistorico Etnografico, and Roman antiquities—including the Zoninus Collar—were relocated to the Museo Nazionale Romano at the Baths of Diocletian.

Today, the collar is on display at the museum’s epigraphy section. Contemporary catalogues recognize it not only for its text but also as a significant material artifact that contributes to our understanding of slavery, communication, and society in Rome. This is part of a broader movement to reintegrate inscriptions with their physical and spatial contexts.

The late 19th century was a turning point for the study of Roman slavery and material culture more broadly. Scholars began prioritizing historical context and accuracy over mere collection and typology.

At this time, slave collars became relevant to conversations about early Christianity—although they would only later be fully integrated into studies of slavery. Ten new collars were discovered in this period alone, with more unearthed in the 20th and 21st centuries, and crucially, archaeologists began recording findspots and related contextual details.

A major milestone was the 1899 publication by Heinrich Dressel of thirty slave collars in the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (CIL). While Dressel maintained the antiquarian habit of treating the collars as texts, organizing them typologically with domestic artifacts like amphorae and lamps, his contribution was groundbreaking in terms of scope and scholarly rigor. He documented more collars than anyone before him, conducted deep bibliographic research, and showed a new interest in archaeological context—evidenced by his work on Monte Testaccio and his lasting typology of amphorae.

Giovanni Battista de Rossi, another pivotal figure in late 19th-century archaeology, helped shift attention toward the collars' function and visual features. In 1874, he published the first comprehensive study of about twenty collars, focusing on their date, materials, and appearance.

Some examples, with Christian symbols like the Chi-Rho (XP) or the palm frond, could be confidently dated to the fourth and fifth centuries—after Constantine’s 313 CE Edict of Toleration. Others mention ecclesiastical roles, suggesting that Christian institutions also owned slaves.

De Rossi and others revived an idea first proposed in the 17th century by Lorenzo Pignorio: that the collars may have replaced facial tattoos as punishment for fugitives after Constantine banned such tattoos for convicts in 315 CE. Support for this theory includes the collars' rarity, their focus on identifying runaways, and their distribution near Rome—possibly indicating that Roman slaveholders, especially in official roles, adhered more closely to the law.

However, the theory is not without problems. It assumes that Constantine’s ban on penal tattoos applied to slaves, despite the fact that tattooing continued into Late Antiquity. Moreover, some collars contain inscriptions discouraging interference with the wearer, suggesting their purpose was not punitive but preventive—to deter theft of valuable slaves. The collars were not uniform in use or meaning.

This raised difficult moral questions for Christian scholars: How could the religion’s followers wear the symbols of faith while owning and branding human beings?

Detail from a marble relief found in Smyrna, showing collared slaves. Credits: D Smith, CC BY-SA 2.0

In response, some 19th-century scholars tried to reinterpret the collars, suggesting they were for animals or that they represented a more humane alternative to facial branding. Neither idea holds up to modern scrutiny. Inscriptions like “I am the slave of…” are clear in their intent, and some collars have been found still locked around human remains. Christianity, it appears, was as complicit in the institution of slavery as the rest of Roman society.

In the 20th century, scholarship began to move beyond this apologetic framing, driven in part by social history and, later, by postcolonial and civil rights movements. The focus expanded from the owners to the enslaved themselves.

The collars, once viewed narrowly as Late Antique Christian artifacts, came to be recognized as evidence of Roman slavery more generally. Historians like Kyle Harper have argued that major changes in the institution of slavery occurred only after the long fourth century, not during it.

Still, the legacy of earlier scholarship lingers. Even modern treatments often separate text from object. Influential works such as Wiedemann’s Greek and Roman Slavery present these collars as inscriptions alone, and major studies like Thurmond’s 1994 work on Roman collars, while rich in textual analysis, include no visual documentation.

Conversely, when the visual aspect is emphasized—such as the prominent image of the Zoninus Collar on the cover of The Cambridge World History of Slavery—the object is often not discussed in the text itself. This reflects a deeply ingrained habit of separating word from artifact.

This division also shapes the broader archaeological study of Roman slavery. Over the 19th and 20th centuries, academic disciplines developed in ways that entrenched the split: historians focused on texts, while archaeologists, particularly classical ones, continued to work within antiquarian frameworks or focused largely on elite monuments.

Only more recently have archaeologists begun shifting toward studying entire contexts and networks, though slavery often remains overlooked. To make real progress, modern scholarship must actively confront and bridge the artificial divide between textual and material evidence—only then can we fully understand the world that produced the Zoninus Collar.

Voices of Control: How Slave Collars made Ownership Visible and Inescapable

The easiest perspective to recover in the study of Roman slave collars is that of the master—after all, it was the owner (or someone acting on their behalf) who commissioned the collar, chose the inscription, and had it fastened around the slave’s neck.

Scholars have most often focused on what these texts say, but Jennifer Trimble in her work The Zoninus Collar and the Archaeology of Roman Slavery also urges us to examine the visual and physical characteristics of the collars to better understand what slave owners hoped to achieve and how their power was made manifest.

Though it’s often assumed these collars served as punishments for attempted escape—perhaps replacing the older custom of tattooing slaves’ faces—a closer inspection reveals more diverse possibilities.

The Zoninus collar, for instance, is made of iron and bronze, materials as harsh and utilitarian as the inscription’s blunt message. The tag itself was cut from a bronze sheet into a rounded rectangle, with an extended strip at the top that folded back to form a hoop. This hoop was then riveted shut, creating a permanent attachment point. The iron neck ring, now heavily corroded, seems to have been formed by twisting doubled wire, which was then threaded through or enclosed by the hoop before being sealed.

The collar’s circumference measures about 37.7 cm—roughly between a small and medium men’s collar size today in the U.S., or a medium to large in women’s sizes. While modern necks may be larger on average, this size would have fit an adult man, woman, or older child in antiquity. These collars were snug enough that they couldn’t simply be pulled off, but they weren’t designed to choke or inflict immediate pain. Their purpose lay elsewhere.

That purpose becomes clearer through the language of the inscription. The Zoninus collar begins with fugi, tene me—“I have run away, hold me.” Many similar collars use nearly identical phrases: tene me ne fugiam (“hold me so I do not run”) or tene me quia fugi (“hold me because I have run”).

Around half also request that the wearer be returned to the owner, with phrases like revoca me or the phonetic variant reboca me. These messages reflect the anxieties of slaveholders, documented in Roman texts: runaways were commonly punished by flogging, chaining, or tattooing. These collars were physical extensions of that fear. Unlike neck shackles, however, they didn’t physically restrain the wearer. Their power was communicative, not coercive.

One interpretation is that these collars were practical tools to assist in recovering runaway slaves. Some included return addresses or indicated the master’s location—for instance, a slave of Minervinus belonged to the 12th Urban Cohort in Rome, and another worked in the office of the urban prefect.

However, the Zoninus collar and several others omit such details. Owners had many other strategies at their disposal: magic spells, public notices, hired slave catchers, friends, and officials. Captured slaves could even be tortured to extract the owner's identity. In that context, the collar was just one element within a complex network of recovery methods.

Another possibility, and the most widely accepted among scholars, is that such collars were imposed as punishment after an escape. The tight fit, public visibility, and first-person wording may have been meant to humiliate the slave, make future flights more difficult, and assert control through both spectacle and shame.

A third theory is that these collars functioned as deterrents, worn even before any escape had occurred. By marking a person as someone to be detained, the collar discouraged attempts in the first place—much like a striped prison uniform today. Including an owner's name or return address reinforced the futility of fleeing.

Economics may also have played a role. Roman law required sellers to disclose if a slave had tried to escape, which lowered the slave’s value. A metal collar could be removed more easily than a tattoo, allowing an owner to conceal a fugitive past if needed before selling the person.

Some collars weren’t about flight at all. A few rare examples—like one preserved in Liverpool—explicitly instruct others not to interfere with the slave:

“By order of our three lords, let no one shelter this slave belonging to someone else.”

These warnings suggest another motivation: preventing the theft or reappropriation of enslaved individuals.

No matter their specific purpose, all these collars projected ownership. On the Zoninus example and others, the owner is named as dominus meus—“my master.” In some cases, the phrase servus sum followed by a name in the genitive is used: “I am the slave of so-and-so.”

A riveted metal collar, especially one bearing an inscription that commands strangers to detain the wearer, made the master’s dominion visible at all times. The command tene me ("hold me") invited others to physically enforce this control, defining a permitted space of presence for the slave—and punishing their movement beyond it.

The act of collaring a slave was not just functional, but also deeply visual. The very shape of the collar, the engraved words, and symbols marked the wearer in ways others could instantly recognize. These symbols could imbue the act with divine legitimacy or public authority.

Across Roman history, marking the bodies of slaves—by whip, ink, or iron—was a persistent motif. In the later empire, this practice expanded: even soldiers and laborers were marked to indicate their group and designated location. Slave collars thus form part of a larger visual and spatial culture that encoded hierarchy and containment on the body itself.

Interestingly, the collars spoke in the first person. The Zoninus inscription reads “I have run away... hold me... return me to my master...”—as though the slave had authored the plea. This ventriloquized voice is typical. The second person also appears: “you will receive a gold coin.” These rhetorical choices mirror Roman traditions of speaking objects—inscribed tombstones, vessels, or even walls that directly address viewers, instructing them to act on behalf of someone absent.

In the case of slave collars, the absent figure is the master, and the enslaved person becomes the medium through which his will is transmitted. The collar transforms a human into a speaking object—a possession that pleads, commands, and testifies to its owner's enduring claim. (The Zoninus Collar and the Archaeology of Roman Slavery, by Jennifer Trimble)

What the Zoninus Collar ultimately reveals is not just the severity of Roman slavery, but the ingenuity of domination. With iron and inscription, the Roman master wrote his authority onto the body of another, making obedience portable and permanent.

This was not just punishment—it was presence. The collar turned the enslaved into a walking message, a silent servant who spoke only in the voice of their owner. Yet centuries later, what survives is more than ownership. In its twisted wire and worn bronze, we see the faint trace of a life once shackled—unnamed, unheard, but no longer entirely forgotten.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: