The Roman Salute, or Saluto Romano: How did the Romans greet each other?

Is the Roman salute, the Nazi salute? History proves it is not.

In the twentieth century, the Roman salute became a widely recognized symbol of Fascism in Italy, Nazism in Germany, Falangism in Spain, and various other right-wing or nationalist movements. Actually, everything started with one painting by Jacques-Louis David, in the late 18th century.

Those performing this gesture would extend their stiff right arm forward and raise it to about 135 degrees from the body's vertical axis, with the hand's palm facing down and fingers together. This salute was purportedly based on an ancient Roman tradition, similar to how the term "Fascism" is linked to the Roman fasces—a bundle of rods with an axe, symbolizing the authority of high Roman magistrates and some priests.

However, the designation "Roman salute" is inaccurate.

No Roman artwork, whether sculpture, coin, or painting, shows such a salute, nor is it recognized in Roman literature or mentioned by ancient historians of either the Republican or Imperial periods. The gestures involving a raised right arm or hand found in Roman and other ancient cultures, as depicted in surviving art and literature, served different purposes and were never identical to the modern straight-arm salute.

Historians have often overlooked modern popular culture, including cinema, which has led to persistent yet unchallenged misconceptions about the Roman salute's origins.

Some historical facts

Firstly, it's essential to grasp the historical background of what is often referred to as the ancient Roman salute. During Roman times, this salute was likely a gesture of respect and deference, commonly used in both military and civic contexts. Historical descriptions and artistic depictions from that era indicate that the salute typically involved raising the right hand, often with the palm facing outward, which differs significantly from the straight-armed, palm-down salute adopted by Fascists and Nazis.

The Fascist and Nazi movements deliberately repurposed and redefined the ancient Roman salute to align themselves with the grandeur and authority of the Roman Empire, attempting to position their regimes as the modern successors to this historic empire. This reinterpretation was especially prominent under Mussolini’s Fascist rule in Italy, where the regime promoted the straight-armed gesture as the "Roman salute" and incorporated it into official protocols and ceremonies. This gesture was subsequently adopted by the Nazis, reinforcing its association with fascist ideology.

However, academic research has largely discredited the claim that such a straight-armed salute was ever used by the ancient Romans. The evidence to support this notion is lacking, indicating that the Fascists and Nazis were engaged in a form of historical revisionism and mythmaking to support their political narratives rather than providing an accurate portrayal of Roman customs.

Roman Greetings and Salutations

The ancient Romans had various forms of greetings and salutations, reflecting their social customs and hierarchy. Here are a few key aspects:

"Salve" and "Vale": Common everyday greetings among Romans included "salve" (hello) and "vale" (goodbye). These were informal and widely used among equals.

Handshake (Dextrarum Iunctio): The Romans also used a gesture similar to the modern handshake, known as the "dextrarum iunctio." This was not just a casual greeting but often had significant implications, such as sealing agreements or symbolizing friendship and loyalty. The handshake typically involved a grasping of each other's forearms, which is more involved than the modern handshake.

"Ave": For higher dignitaries or officials, the term "ave" (hail) was used, often in a more formal context. This greeting was famously used to address emperors and notable leaders.

Kissing: In more personal settings, kissing was a common form of greeting among Romans. Depending on the social status and intimacy, they might kiss the cheeks, hands, or even the mouth. This form of salutation was reserved for close friends or family.

Military Salute: The idea of the Roman military salute, often thought to involve touching or raising the hand to the forehead, is a bit of a modern myth popularized by cinema and not historically documented in ancient texts. The military likely used more practical verbal greetings and strict protocols based on rank and situation.

Gestures and Body Language: Romans also used various body language cues and gestures as part of their greetings. For example, spreading arms wide could indicate a welcoming gesture.

Roman Gestures or Behaviours

In ancient Rome, four specific types of gestures or behaviors were commonly recognized:

Adlocutio – This was a formal greeting exchanged between the leader, typically the emperor, and his army. The leader would address his soldiers, and they would respond in kind.

Acclamatio – This involved public expressions of approval or disapproval, contentment or dissatisfaction, which were typically vocalized. The nature of the shouts varied with the occasion: for weddings, the cries would be "Io Hymen, Hymenaee" or "Talassio"; during triumphs, the shouts would be "Io triumphe, Io triumphe"; and orators or performers might be praised with phrases like "Bene et praeclare," "Belle et festive," or "Non potest melius."

Adventus – This ceremony marked the arrival of the emperor into the city, typically Rome, either during ongoing conflicts or following their conclusion.

Profectio – This was a farewell ceremony held when a consul (during the Republic) or the emperor (in Imperial times) departed from the city.

Did the Romans actually say “Hail Ceasar?”

The Latin greeting "Ave" translates to "hail, be well".

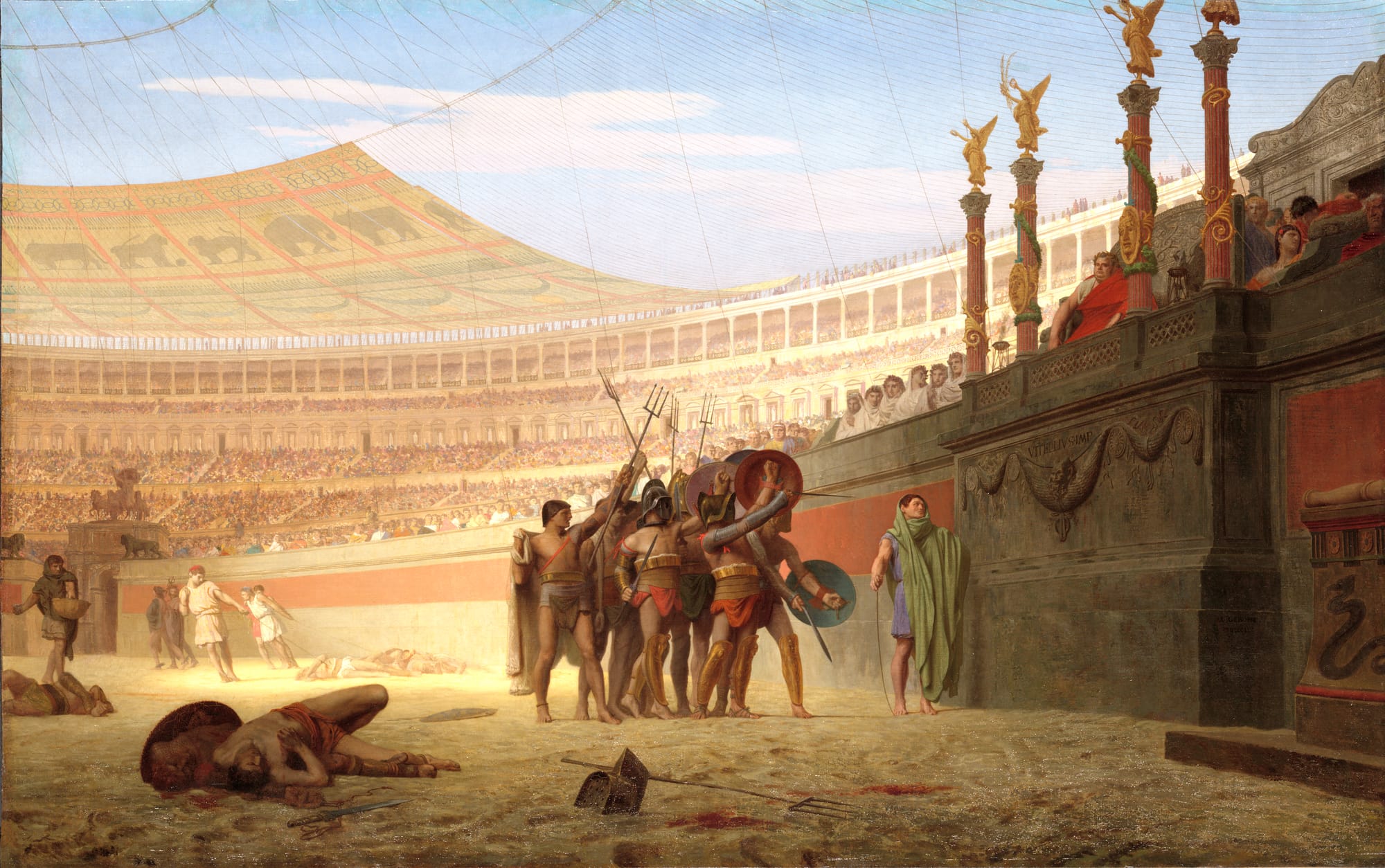

Suetonius in his "Lives of the Caesars" recounts that gladiators in the arena would address the Roman emperor with the phrase, ‘Ave Caesar, morituri te salutant [Hail Caesar, those who are about to die salute you]’.

This salute symbolized the gladiators' respect and recognition of the emperor's authority before they faced potential death in combat.

This salute symbolized the gladiators' respect and recognition of the emperor's authority before they faced potential death in combat.

Illustration Midjourney

Where is the truth?

As Martin M. Winkler states in his book, “The Roman Salute”, salutations varied widely across ancient cultures. Notably, in the ancient Near East, the standard greeting involved raising one's right hand to the forehead. In classical Greece, greetings included raising a hand to greet someone on the street and also handshaking, known as linking hands. Similarly, ancient Roman gestures included the 'dextrarum iunctio,' which involved the joining of right hands, and in military settings, a salute similar to the contemporary military gesture of raising the right hand to the head.

Despite these practices, visual evidence from the period, such as sculptures on significant Roman monuments like the Arch of Titus, the Arch of Constantine, and the columns of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius, which commemorate military campaigns and victories, do not conclusively depict the raised-arm or "Roman" salute. These well-known monuments, ideal for showcasing such a gesture if it had been customary, do not display any clear instances of this form of salutation.

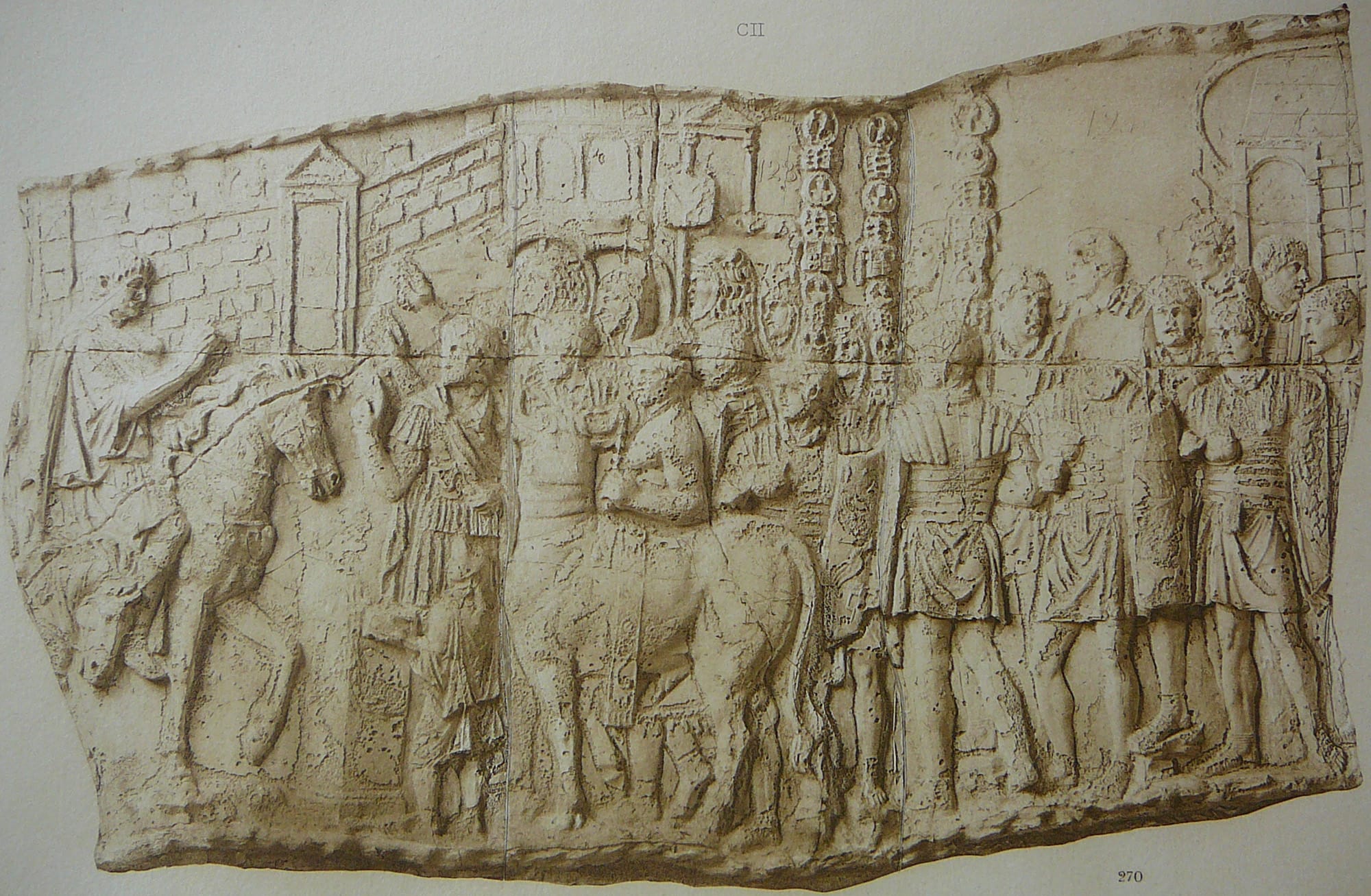

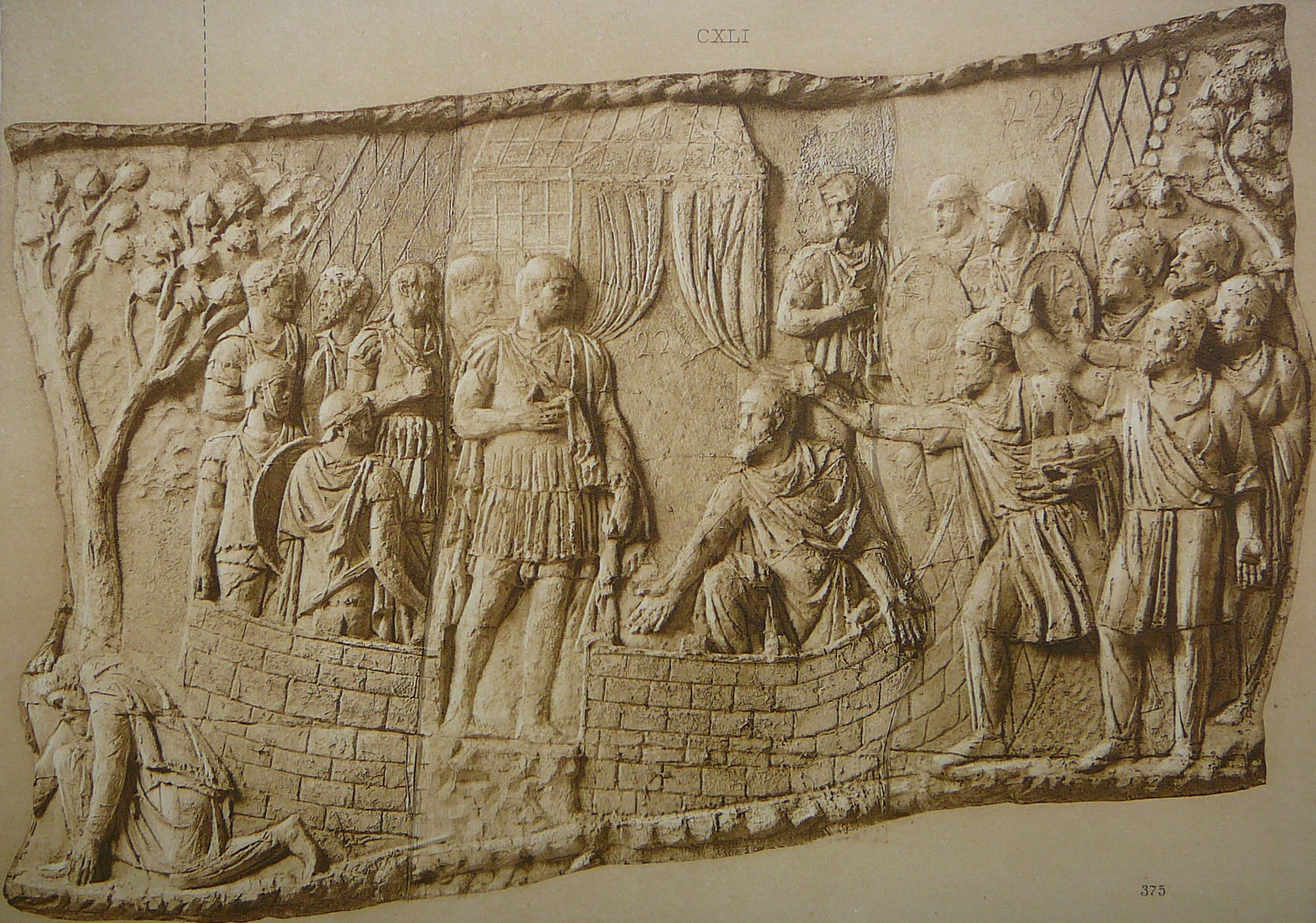

Three scenes depicted on Trajan's Column, categorized using the numbering system originally introduced by Conrad Cichorius, warrant attention. These scenes are detailed through excerpts from descriptions provided alongside their photographs in the publication by Filippo Coarelli.

Plate LXII, Scenes LXXXIV–LXXXV (Cichorius) = Plate 99 (Coarelli):

Before Trajan conducts a sacrifice, “crowds of onlookers . . . raise their arms to salute the emperor.” Only half of the six or so raised arms are clearly extended straight, the others are bent at the elbow. On the straight arms, only one palm is open but held vertically; on the others, thumb and index finger are extended, the other fingers are bent back. The fingers on the hands of three of the bent arms are pointing downwards. (Figure 1)

Plates LXXIV–LXXVI, Scenes CI–CII (Cichorius) = Plates 122–123 (Coarelli): “The emperor on horseback . . . is welcomed outside the walls of a city by a unit of legionaries, preceded by a high-ranking officer, trumpeters (cornicines) and standard-bearers.” Of the fifteen or so legionaries depicted, none is raising his entire arm. The officer, facing Trajan, is holding his upper right arm close to his body; the lower arm is raised, with the index finger pointing up and the other fingers closed. Above (i.e., behind) him, two raised right arms display hands with fingers spread wide. Trajan himself is holding his upper right arm close to his body, extending only the lower part. The marble forming his hand is damaged, so the exact position of the fingers is unrecognizable. No straight-arm salute occurs in this scene. (Figure 2)

Plate CIII, Scene CXLI (Cichorius) = Plate 167 (Coarelli): In his last appearance on the column, Trajan “is about to receive an embassy of Dacian pileati [men wearing felt caps] who are escorted by auxiliary troops.” Three of the Dacians are extending their right arms toward Trajan, their open hands held vertically and their fingers spread. None of the Romans is returning their gesture. (Figure 3)

The Column of Marcus Aurelius, similar to Trajan’s Column, displays gestures of raised right arms with fingers spread apart. Scenes that come closest to resembling the raised-arm salute are found in Roman sculpture and on various coins and medallions, depicting events such as adlocutio ("address"), acclamatio ("acclamation"), adventus ("arrival"), or profectio ("departure").

These scenes typically involve a high-ranking official—often a general or the emperor—greeting or addressing individuals, usually soldiers. The late Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus provides a detailed account of such an event during Emperor Constantius II's arrival in Rome in AD 357.

In these depictions, unlike modern salutes where both the leader and the crowd might raise their arms, it is generally only the high-ranking individual who extends his right arm as a sign of greeting and benevolence, primarily symbolizing his authority.

This aspect of power associated with the gesture is emphasized significantly in artistic representations. For example, a marble relief depicting Emperor Domitian's departure on a military campaign, housed in the Palazzo della Cancellaria in Rome, features the figures of the Senate and the Roman People, both idealized as the genius populi and the genius senatus, respectively, who raise their right arms in a farewell gesture.

However, these gestures do not resemble the modern raised-arm salute. Domitian’s arm is raised horizontally, not as high as the Senate figure. Similar depictions on Roman coins show the emperor raising only his lower arm from the elbow, suggesting these gestures symbolize power rather than salutation.

Visual evidence and Roman imperial literature further confirm this interpretation. The emperor’s raised right hand (dextra elata) is frequently depicted as a symbol of imperial power in the poetry of Statius and Martial. For instance, in a consolation poem written for Abascantus, Domitian’s secretary, by Statius, the dying wife recalls her husband's proximity to the emperor with the words, “I saw you approach ever more closely the right hand on high”. Similarly, Martial’s epigrams describe the emperor’s right hand as the most powerful on earth, reinforcing the notion that these gestures, often seen in depictions of imperial adventus, are laden with meanings of sovereign authority.

The Roman Salute is not the fascist salute

The Prima Porta marble statue of Emperor Augustus, discovered in 1862 and currently housed in the Vatican Museums, is perhaps the most renowned depiction of a Roman figure with his right arm raised, addressing someone.

This statue is followed in fame by later equestrian bronze statues, which may depict Emperor Caligula in Naples, Nero in Ancona, and Marcus Aurelius on the Campidoglio in Rome. However, contrary to popular belief, the statue of Augustus does not depict him saluting or engaging in an adlocutio. It has been noted that the statue’s right arm, which is raised, is not the original but was restored in antiquity, possibly on more than one occasion.

Originally, the hand of Augustus' raised arm in the Prima Porta statue was holding a spear, with the tip resting on the ground. The ring finger of this hand, which has survived separately, points downward. In contrast, the statue of Marcus Aurelius shows the emperor's right arm extended but not raised to even a horizontal level, and his hand and fingers are not outstretched. Despite this, the statue was used as a model for an equestrian statue of Benito Mussolini by Giuseppe Graziosi and became a backdrop for Fascist rallies.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: