The Magnificent Baths of Caracalla

The Baths of Caracalla, an expansive public bath complex stands as one of the most impressive architectural feats of the Roman Empire.

Nestled in the heart of Rome, the Baths of Caracalla are a monumental reminder of ancient Rome's grandeur and sophistication. Constructed under the reign of Emperor Caracalla between 212 and 217 AD, this expansive public bath complex stands as one of the most impressive architectural feats of the Roman Empire, showcasing the zenith of Roman engineering, architecture, and artistic decor.

The Baths of Caracalla, commissioned by Emperor Septimius Severus, were completed by his son, Caracalla, in the early 3rd century AD. This grand public space was not just a place for bathing but a center for socializing, exercise, and relaxation.

The formal Roman Latin designation for the Baths of Caracalla was Thermae Antoninianae, which translates to Antonine Baths in English, named so due to Emperor Caracalla's surname, Antoninus.

The baths of Caracalla in Rome were the city's second-largest public bathing complex, surpassed only by the Baths of Diocletian, and remained active until the 530s before being abandoned and falling into decay.

Throughout their history and beyond, the Baths of Caracalla have influenced the design of numerous significant structures, both ancient and contemporary, including the Baths of Diocletian, the Basilica of Maxentius, New York City's original Pennsylvania Station, Chicago Union Station, and the Senate of Canada Building. Among the treasures unearthed from the site are renowned sculptures like the Farnese Bull and the Farnese Hercules.

Construction and Design

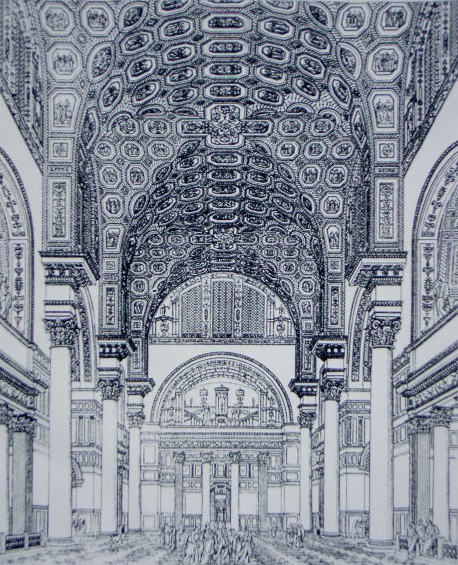

Utilizing a variety of materials, including marble, granite, and brick-faced concrete, the baths were a marvel of construction. The extensive use of pozzolana cement, a volcanic ash that hardens underwater, allowed for the creation of massive yet stable structures, including the baths' soaring domes and vaults.

It took 9,000 workers five years, (from 211 to 216 AD), to construct the primary structure of the Baths of Caracalla. Prior to construction, more than 10,000 prisoners from what is now Scotland, specifically Caledonians, were tasked with clearing the site. Following the completion of the baths in 216 AD, additional elements such as pleasure gardens, walls, and various other structures were developed between 217 and 222 AD under the reign of Emperors Heliogabalus and Severus Alexander.

How were the Baths of Caracalla adorned?

Caracalla did not hold back on lavish adornments for the baths. The décor featured exquisite marble columns and slabs imported to embellish the floors and walls, alongside costly marble statues and vibrant mosaics. Some vaults boasted mosaics made of glass paste, while others were adorned with ornate stucco work. Today, much of the marble decoration has been lost, though remnants can still be spotted on the walls.

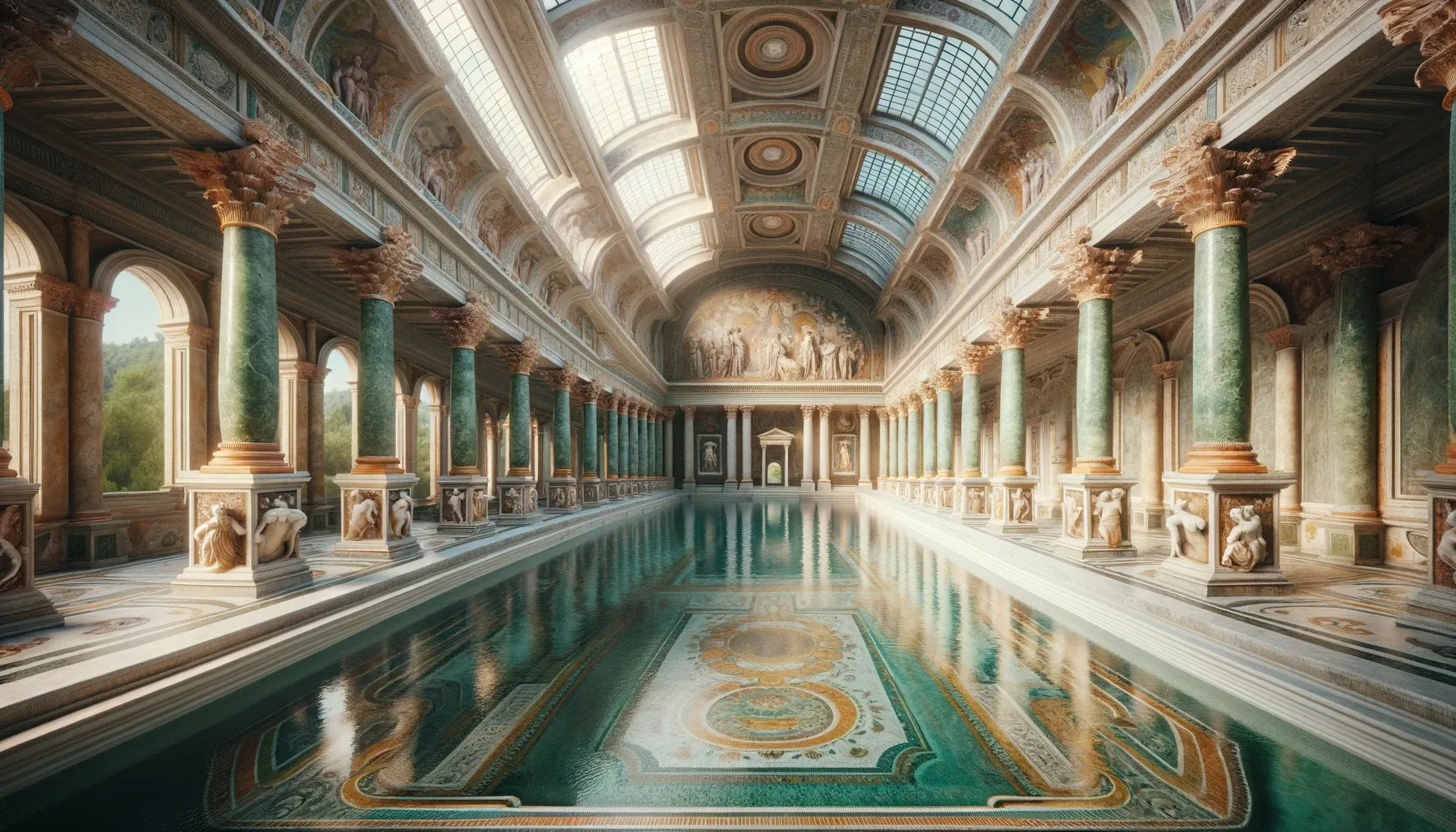

However, many of the original floor mosaics, including those with colorful geometric designs and black-and-white maritime scenes, remain at the site. Mosaics depicting athletes, once part of the gymnasium areas, are now preserved in the Vatican Museums. The baths' design exuded extravagance, from the towering vaults to the marble-lined walls and vivid mosaics. The sunlight that filtered through the windows once reflected off the water features, casting shimmering light over the polished marble surfaces and sparkling glass mosaics, creating a dazzling effect in the public spaces. Yet, a significant part of the structure was concealed from public view, adding to the complex's mystique.

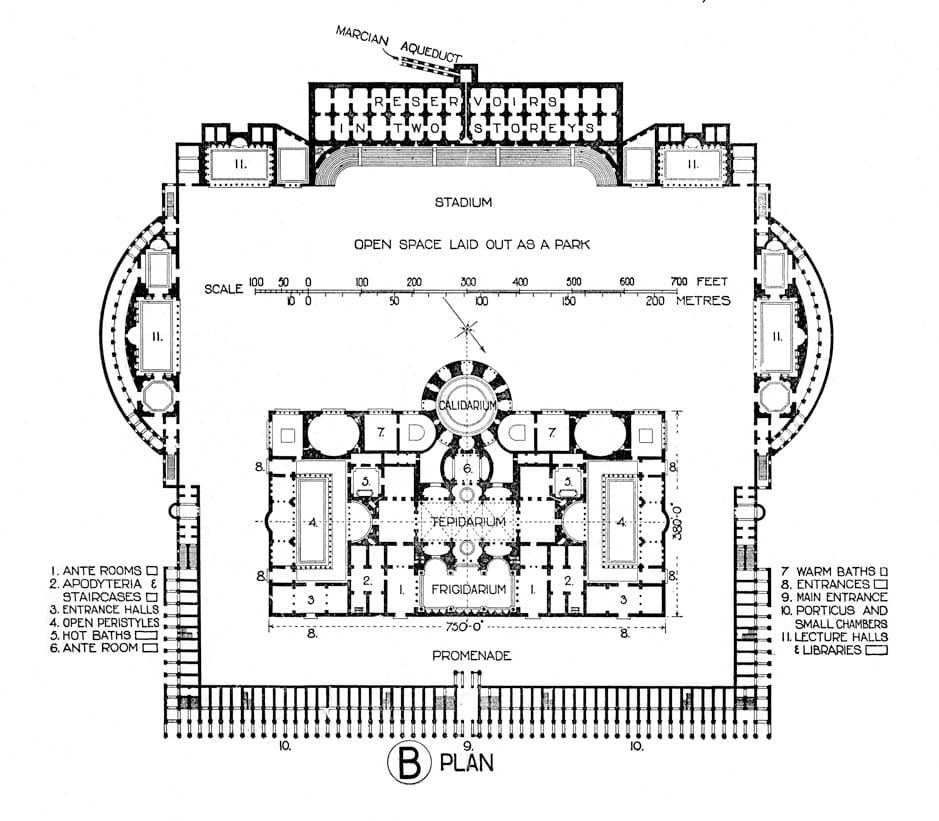

In typical Roman fashion, the thermae played a crucial role in public life, especially for the majority of citizens who resided in densely populated apartment buildings lacking access to running water or sanitation. For every visitor, the initial visit was to either the men's or women's apodyterium (changing area), where they could place their attire in personal lockers. The bath's layout was organized around its short axis, featuring the caldarium (hot bath) and a smaller tepidarium (warm bath), with the frigidarium (cold bath) positioned centrally, complemented by the natatio, an outdoor swimming pool.

Surrounding these main baths were symmetrically placed rooms designated for changing, massage, hair removal, and health treatments. Visitors would move from the changing areas to the gymnasia for physical exercise in the palaestra, then to a sauna for further sweating. Following this, bathers would proceed to the caldarium, use a strigil to cleanse their skin, cool down in the tepidarium, and finally take a refreshing dip in the frigidarium, as advised by the physician Galen. Guests could also enjoy sculptures, swim in the natatio, peruse the libraries or stroll the premises.

How big were the Baths of Caracalla?

The Baths of Caracalla were designed based on the model set by the Baths of Trajan but incorporated several remarkable advancements. For instance, they were surrounded by a perimeter almost 500 yards square, encompassing nearly fifty acres. The dome over the caldarium rivaled the Pantheon's in size but was significantly higher. Extending beyond the main structure, its large drum windows captured the afternoon sunlight and overlooked the gardens. The central hall was upheld by eight massive columns, one of which now stands in the Piazza della Trinità in Florence.

The expenditure on building the Baths of Caracalla was undoubtedly vast. Spanning the area of more than two football fields, the structure's sheer size demanded an extraordinary amount of resources. It is calculated that during the six-year construction period, the daily requirement for bricks and concrete amounted to 2,000 tons.

This extensive use of bricks was due to the construction primarily utilizing brick and concrete. Additionally, the interior's marble surfaces, now missing, served merely as a decorative overlay.

Out of the original 250 columns, roughly two dozen remain, repurposed in a basilica and a public square. Evidence of holes in some of the higher walls suggests parts of the baths featured extensive wooden balconies, from which spectators could observe the bathers and those engaging in exercise below.

The mosaic floors

Centuries of looting stripped the Baths of Caracalla of nearly all their original ornamental marble floors, wall panels, and various adornments, yet remnants of the mosaic flooring have withstood the test of time.

These surviving mosaics are remarkably captivating, offering a window into the former grandeur and vibrant aesthetics of the baths. The mosaic tiles create an array of designs, from simple two-toned and colorful abstract patterns to depictions of marine life and Roman athletes.

These extensively restored mosaics, once adorning the floors of the public libraries within the baths' eastern and western exedrae, are segmented into square and rectangular panels. The square panels showcase busts, while the rectangular ones feature full-length figures of athletes, often depicted with their hair tied in a cirrus—a knot at the back of the neck indicating a professional athlete.

The wrestlers are shown with their arms covered in cesti, made from leather or fabric with metal parts, highlighting the detailed portrayal of their muscular physique and dynamic facial expressions through a rich mix of colored tesserae. Judges in togas, overseeing the contests, are also depicted. Although the Baths of Caracalla were constructed in the early 3rd century AD, it is believed these mosaics were added during renovations in the early 4th century AD.

Not just baths

Although commonly referred to as "baths," the bathing facilities represent just a segment of these expansive complexes. Situated near Rome's Aventine Hill, the Baths of Caracalla extend over an area of about 27 acres, enclosed by a substantial perimeter wall. The northeast boundary of the complex was flanked by public storefronts, which also covered sections of the northwest and southeast walls. The principal entry was positioned in the middle of the northwest wall, leading visitors into a domain of carefully tended gardens that prefaced the bathhouse itself. These gardens encircled the bathing facility, complete with vegetation, pathways, and water features.

Sections of the southeast and northwest walls were architecturally fashioned into vast exedrae, semicircular spaces housing additional facilities like gymnasia, lecture rooms, and nymphaea (grand fountains or water-themed grottos). The complex also housed two sizable libraries, one dedicated to Greek literature and the other to Latin, with only one surviving today, albeit in a ruined state. It contains 32 niches that once supported wooden shelves for papyrus scrolls.

A grand niche with a semidome located directly across the entrance once displayed a statue, while the floor boasted opus sectile flooring crafted from luxurious marbles. Masonry benches along the room's perimeter provided seating. Several marble columns from the library stood for centuries before being relocated in the 12th century to the Church of Santa Maria in Trastevere, Rome.

Adjacent to each library were two grand staircases connecting the complex's southwestern edge with the Aventine Hill. Positioned between the libraries was a stadium designed for athletic competitions, doubling as a racetrack, and encircled by spectator seating. Furthermore, a sizable two-story reservoir, linked to the Aqua Antoniniana, along with various cisterns throughout the grounds, ensured the supply of water to the baths and fountains via subterranean pipelines.

It is reported that the baths could host 1,600 bathers simultaneously and cater to around 8,000 visitors daily. Indications of a second floor in certain sections of the building, suggested by the presence of staircases, exist, although the ruins of this upper level are too fragmented to ascertain its purpose.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: