The Four Journeys of Hadrian, the Globetrotter Emperor of the Roman Empire

Hadrian, who reigned as Roman Emperor from AD 117 to 138, is widely regarded as one of the most traveled emperors in Roman history.

Hadrian’s extensive travels were a hallmark of his reign and were unparalleled compared to many other emperors. His journeys took him across the empire, including provinces in Europe, Asia, and Africa, showcasing his deep interest in overseeing the empire's affairs firsthand.

Hadrian's motivation for travel was partly administrative, ensuring the stability of the empire by visiting its farthest reaches, inspecting military installations, and engaging with local populations. But he was also deeply curious about the cultures, architecture, and history of the places he visited.

His travels helped to bolster the authority of the emperor while also demonstrating his dedication to the empire’s well-being.

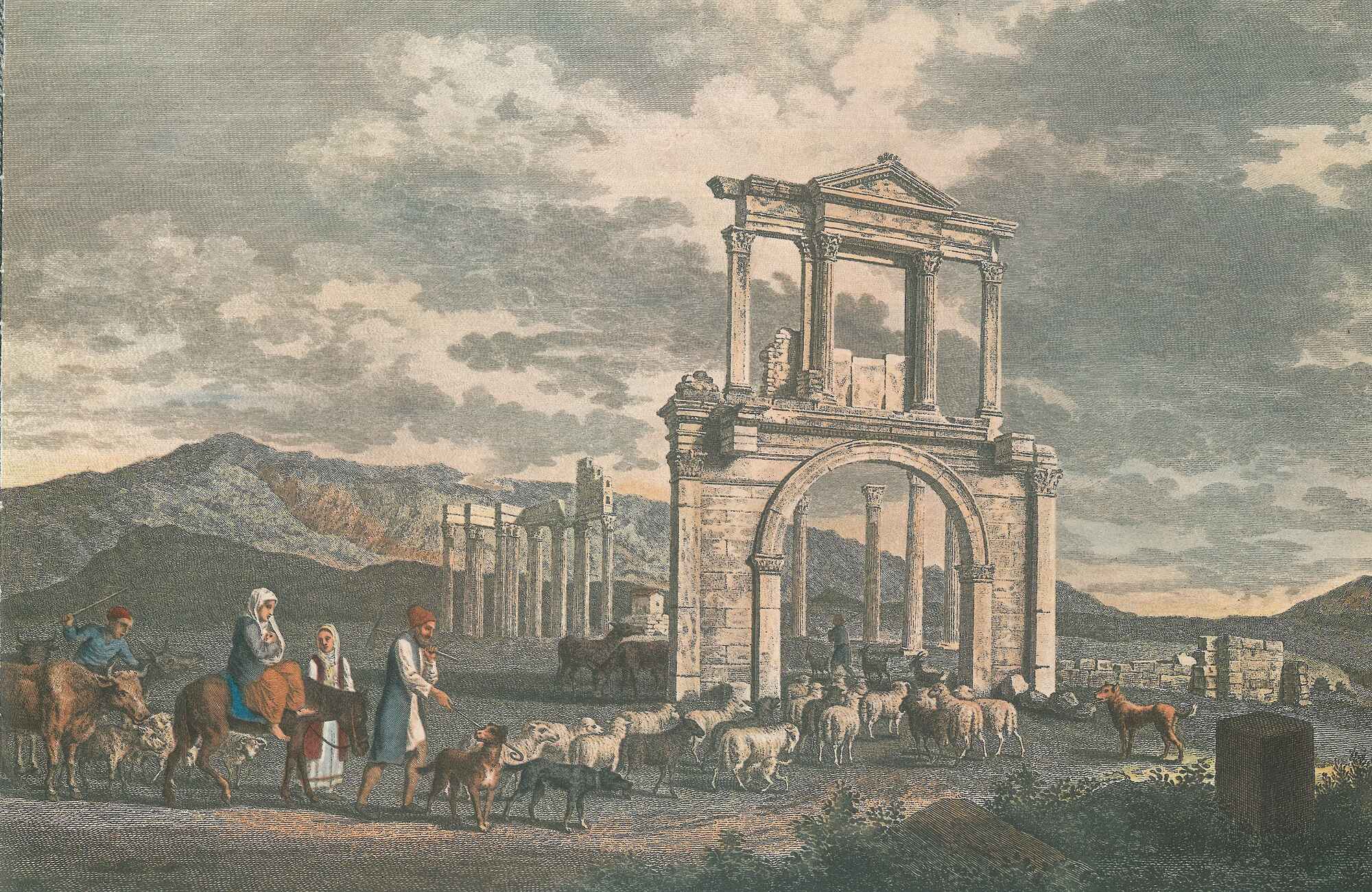

Arch of Hadrian in Athens, by James Stuart & Nicholas Revett. Public domain

Hadrian and his Travels

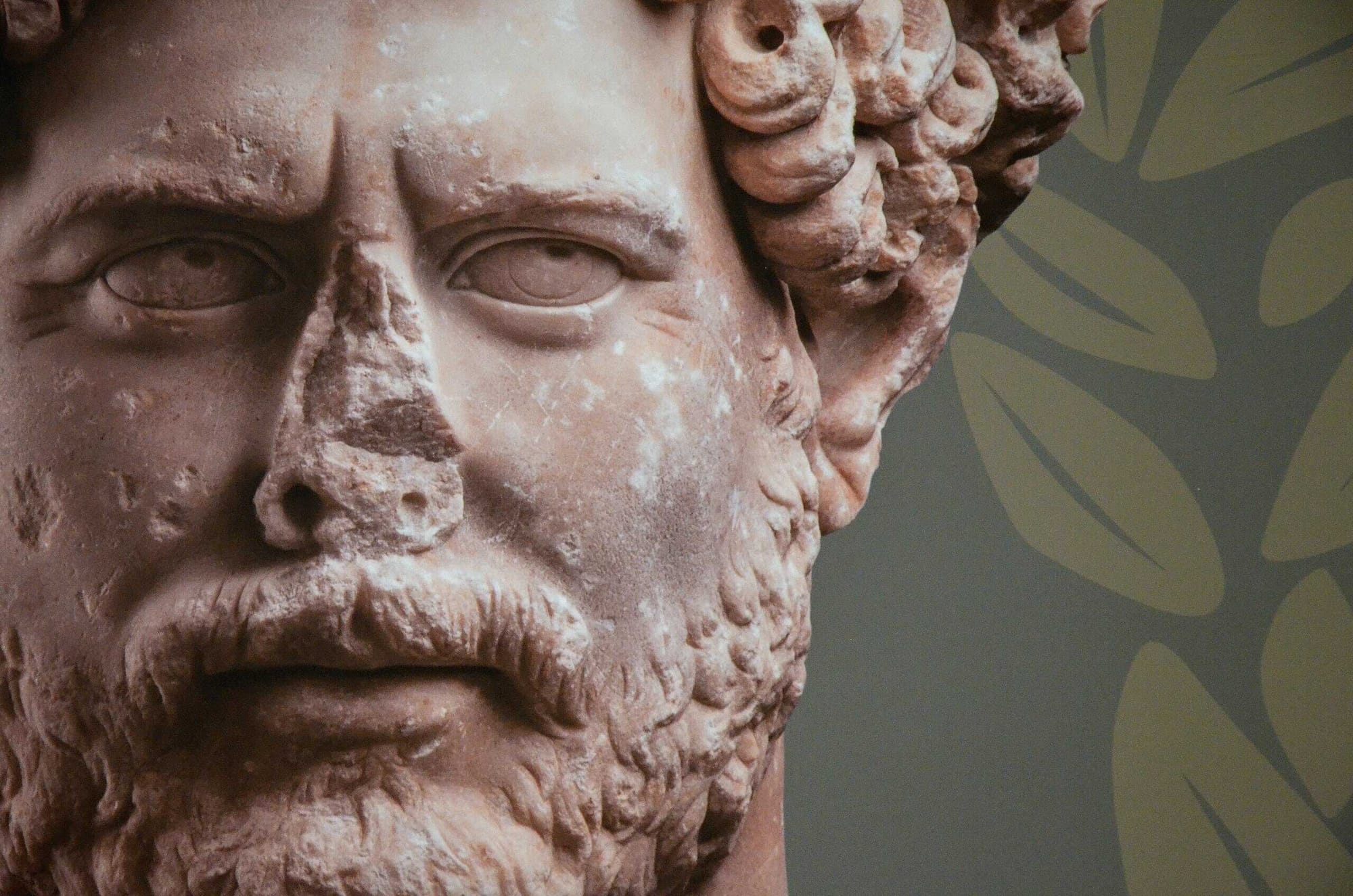

Hadrian is depicted in ancient sources as a skilled administrator, capable military leader, intellectual, and admirer of Greek culture. He was known for his religious tolerance and scholarship, but also had a reputation for being cruel, petty, and vindictive.

These conflicting qualities—his efficiency as a ruler and his difficult personal relationships—have sparked much scholarly debate, leading to his portrayal as an enigma. He is often seen as embodying the traits of a Roman magistrate, a Hellenistic monarch, an Egyptian pharaoh, a philosopher, and even a magician.

This complex personality mix makes it hard to pin down a single image of him, leading his biographer Anthony R. Birley to conclude that Hadrian is best understood through his actions: "For us, at least, Hadrian has to be what Hadrian did."

Hadrian is particularly remembered for his extensive travels, dedicating more than half of his twenty-year reign (A.D. 117-134) to touring the Roman provinces. This characteristic of his rule was heavily emphasized by ancient writers, and his journeys were even "predicted" in the Oracula Sibyllina, (The Sibylline Oracles are a collection of oracular utterances written in Greek hexameters ascribed to the Sibyls, prophetesses who uttered divine revelations in a frenzied state) which described him as visiting and dedicating temples across the world while promoting universal peace.

Hadrian’s Travel Companions

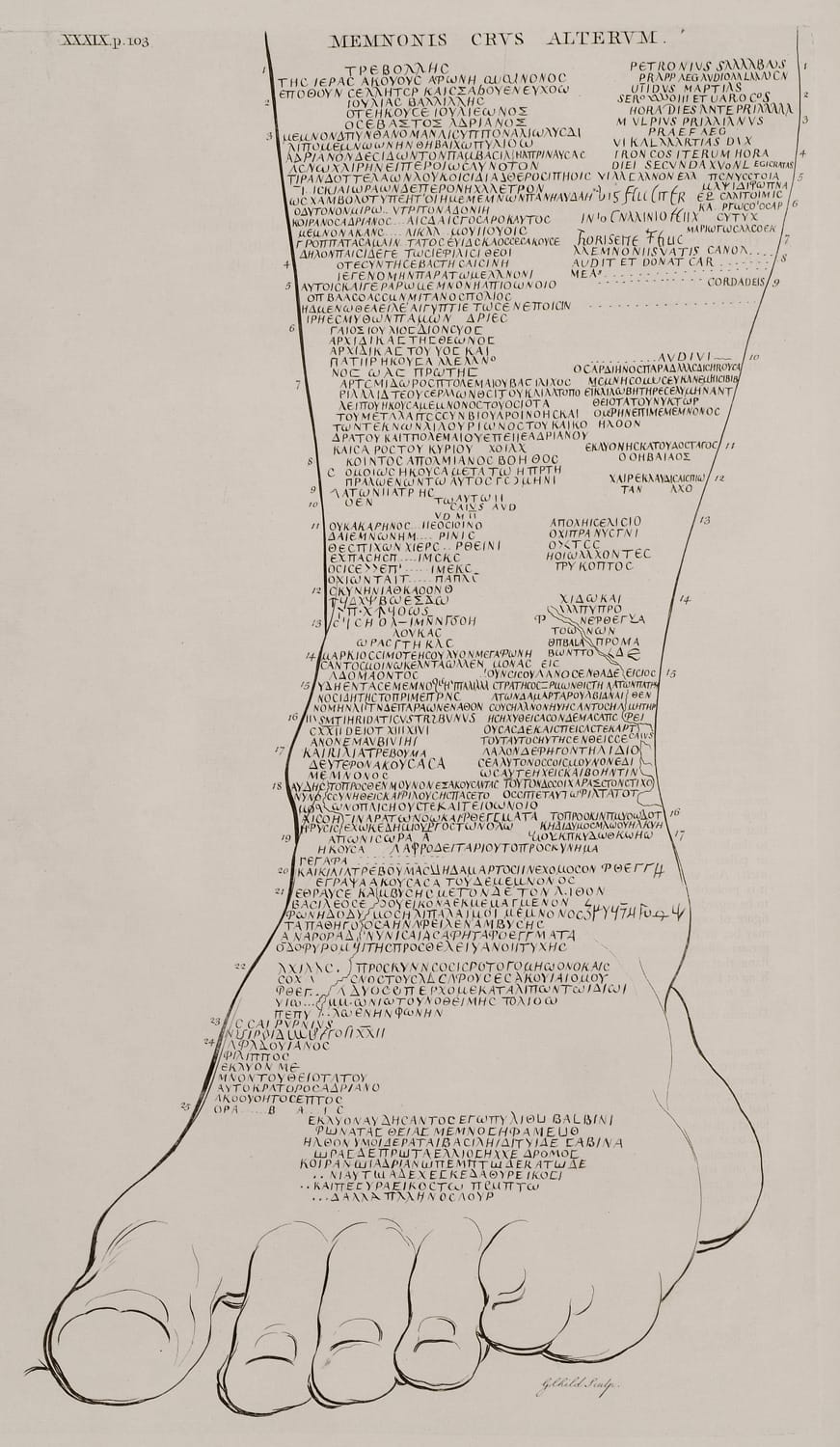

Despite his reputation as a great traveler, only seven of his companions are specifically named in historical sources, including his wife Sabina, poetess Julia Balbilla, his favorite Antinous, and a few others such as Palemo of Laodicea and Titus Macrinus.

While these companions accompanied him, they are only directly mentioned during specific instances, with little information surviving about their activities. For example, Sabina is explicitly mentioned during Hadrian’s visit to Thebes in A.D. 130.

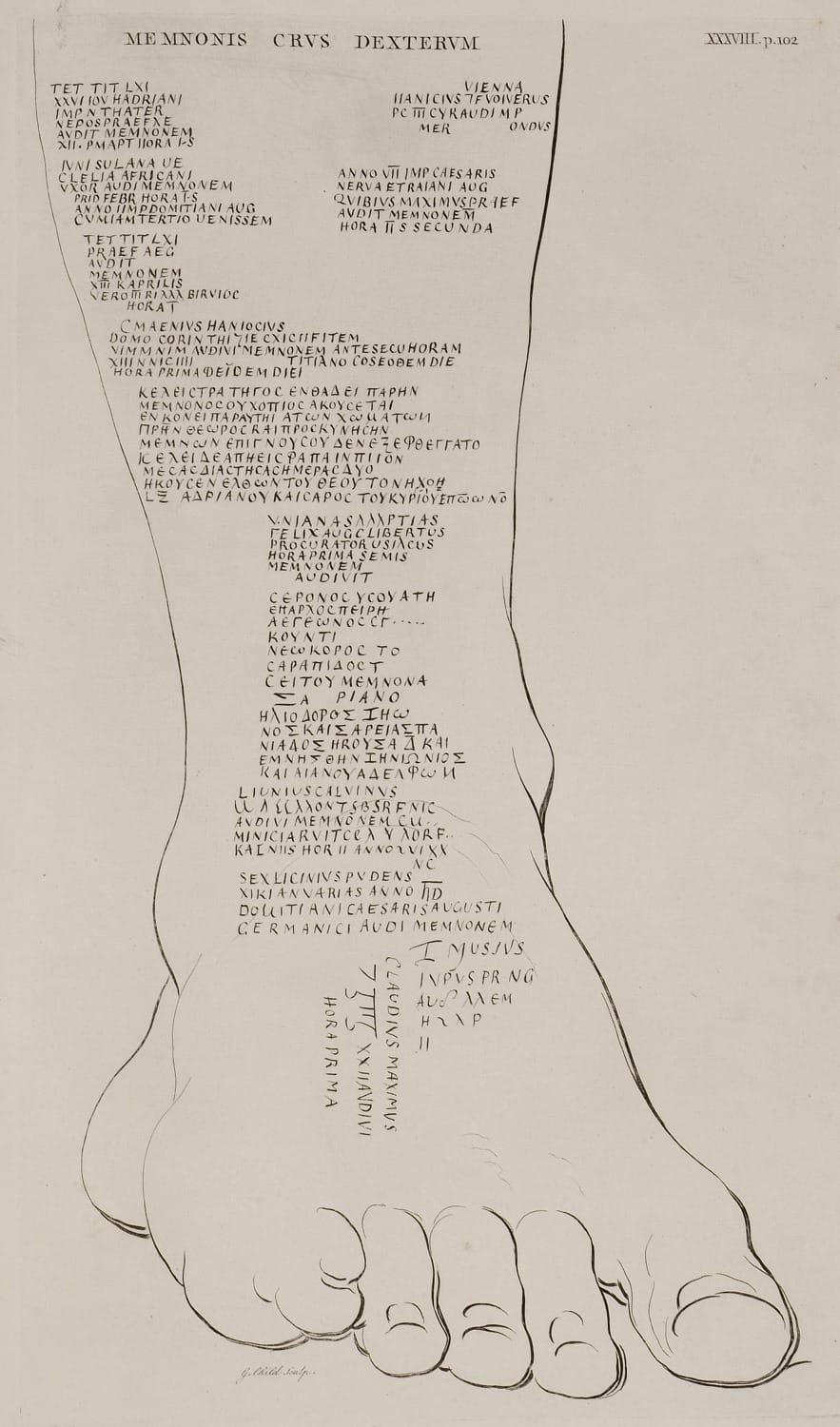

On their journey along the Nile, Balbilla inscribed a record of their visit on the statue of Memnon. Hadrian was particularly intrigued by the "singing" statue of Memnon, a colossus of Amenhotep III that produced a strange musical sound in the morning, a phenomenon that he returned to observe multiple times.

Antinous, Hadrian's beloved, is notably seen accompanying the emperor during a lion hunt near Alexandria. Antinous died later that same year, reportedly by drowning in the Nile under mysterious circumstances. While Hadrian claimed it was an accident, some speculated that Antinous had been sacrificed. In honor of his memory, Hadrian founded the city of Antinoopolis near the site of Antinous' death. (Traveling Companions of Hadrian, by Richard H. Chowen)

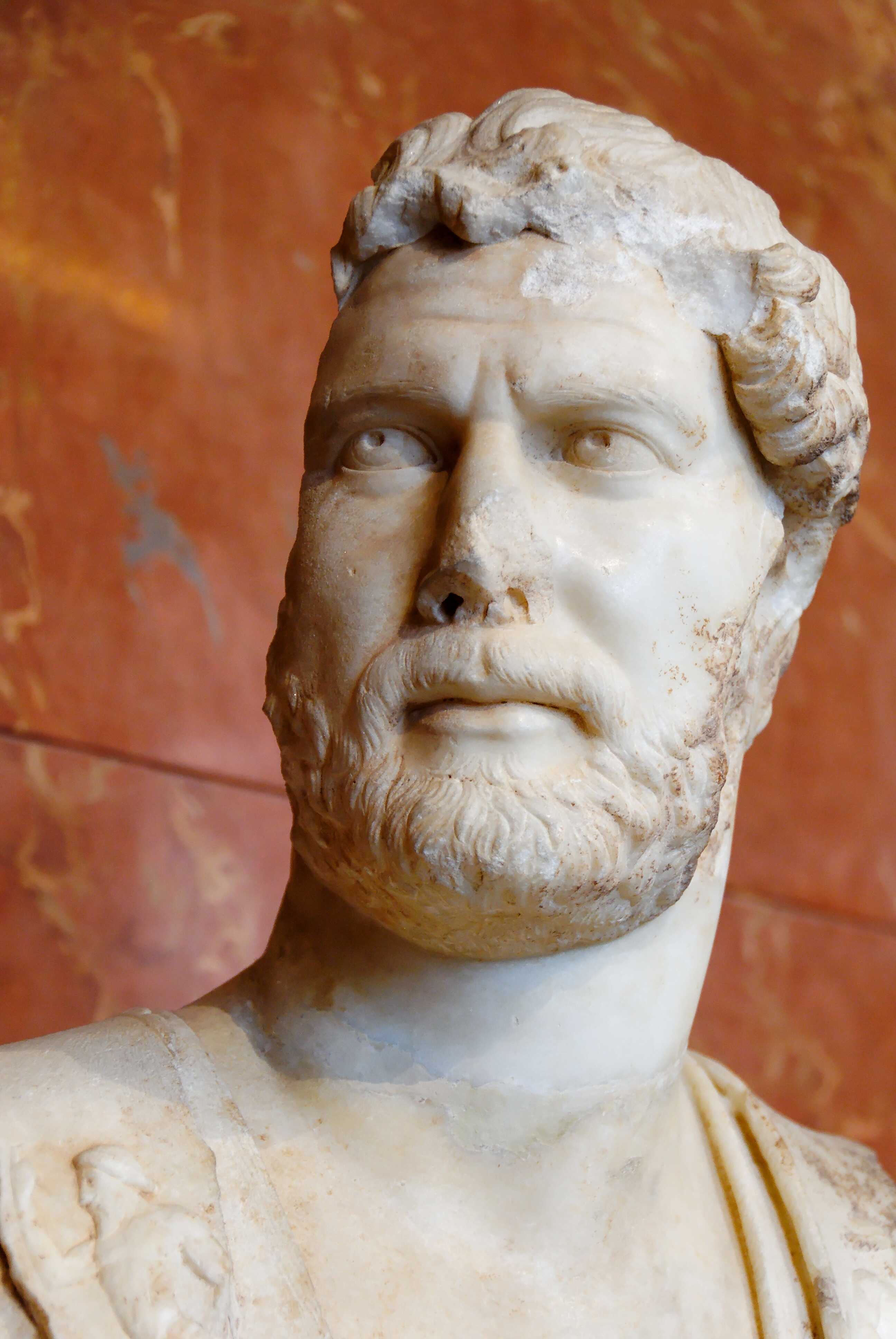

His Portraits throughout the Empire

Hadrian's extensive travels have been suggested to influence the large number of surviving portrait statues of him, as noted in a recent handbook on Roman sculpture. The abundance of his portraits is attributed to two main factors: his lengthy reign of twenty-one years and the widespread erection of statues in cities across the empire either in anticipation of or in appreciation for his visits.

His provincial tours not only affected the number of portraits but also impacted the established chronology of his portrait types. Scholars have suggested that the high concentration of Hadrian's portraits found in the provinces can be explained by these travels. This also raises the possibility of linking certain provincial portraits with the emperor’s visits to specific regions, which could provide significant chronological markers for dating these works. (Imperial visits as occasion for the erection of portrai statues?, by Jakob Munk Hojte)

“Hadrian travelled through one province after another, visiting the various regions and cities and inspecting all the garrisons and forts. Some of these he removed to more desirable places, some he abolished, and he also established some new ones.

He personally viewed and investigated absolutely everything, not merely the usual appurtenances of camps, such as weapons, engines, trenches, ramparts and palisades, but also the private affairs of every one, but of the men serving in the ranks and of the officers themselves, — their lives, their quarters and their habits — and he reformed and corrected in many cases practices and arrangements for living that had become too luxurious.

He drilled the men for every kind of battle, honouring some and reproving others, and he taught them all what should be done. And in order that they should be benefited by observing him, he everywhere led a rigorous life and either walked or rode on horseback on all occasions, never once at this period setting foot in either a chariot or a four-wheeled vehicle.

He covered his head neither in hot weather nor in cold, but alike amid German snows and under scorching Egyptian suns he went about with his head bare.

In fine, both by his example and by his precepts he so trained and disciplined the whole military force throughout the entire empire that even today the methods then introduced by him are the soldiers' law of campaigning.

This best explains why he lived for the most part at peace with foreign nations; for as they saw his state of preparation and were themselves not only free from aggression but received money besides, they made no uprising.

So excellently, indeed, had his soldiery been trained that the cavalry of the Batavians, as they were called, swam the Ister with their arms. Seeing all this, the barbarians stood in terror of the Romans, they employed Hadrian as an arbitrator of their differences.”

Cassius Dio, Epitome of Book LXIX

The First Journey of Hadrian

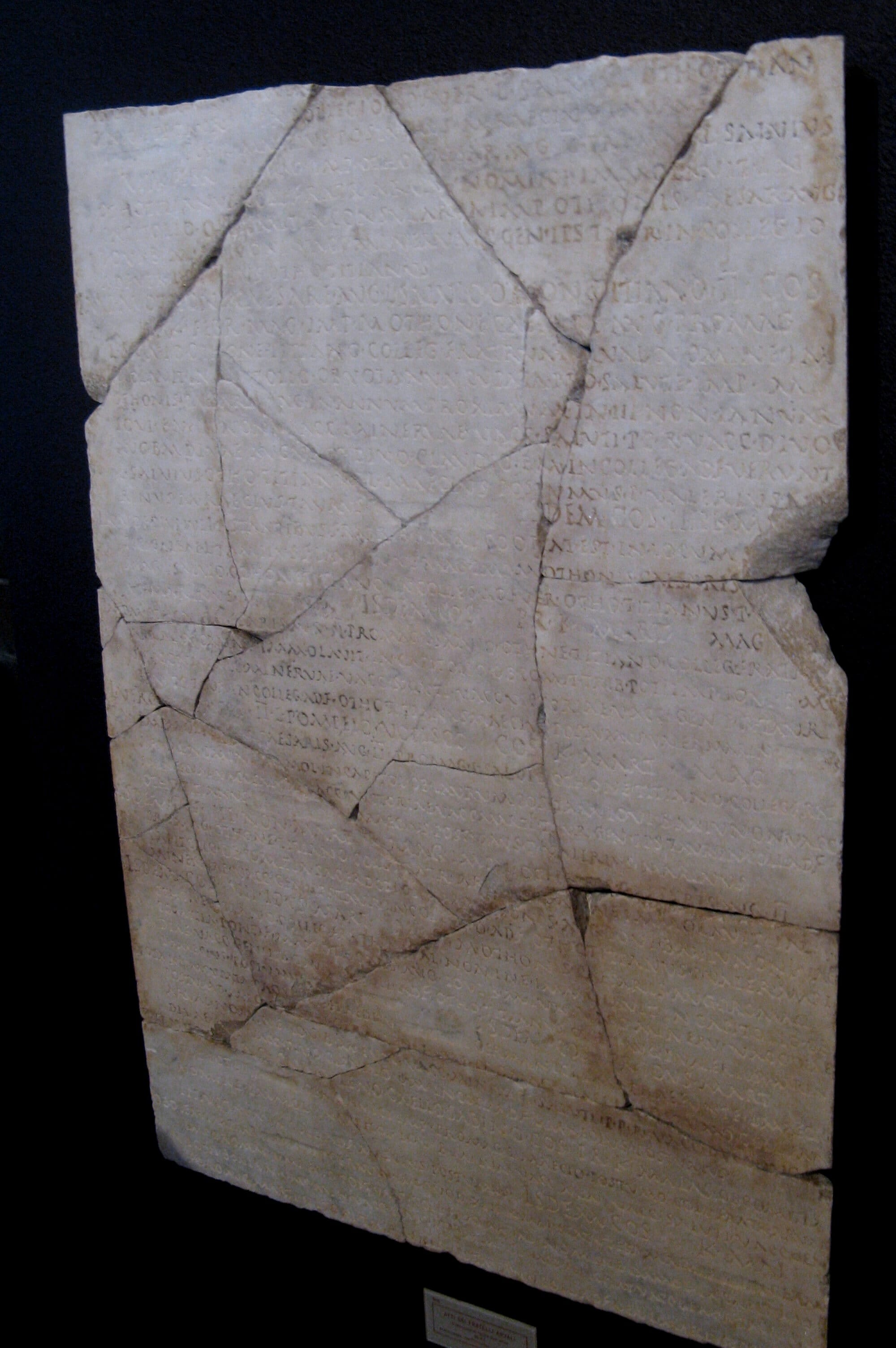

The one that started them all, begun soon after he was declared emperor by the Syrian army on August 11, 117, and is notably documented through epigraphic evidence.

A fragment found in Rome lists key locations along the route from Tarsus to Caesarea, beginning with Mopsucrene, and dates his journey from October 12 to 19. The local dignitary, Latinius Alexander, assisted in accommodating Hadrian's troops in Ancyra, while by November 11, the emperor sent a letter to Pergamum from Juliopolis, a town on the way to Nicomedia. Hadrian likely spent the winter in Nicomedia, an ideal place for imperial residence during colder months.

His journey culminated in his arrival in Rome on July 9 of the following year, as attested by the Acta of the Arval Brethren (a body of priests who offered annual sacrifices). During this time, notable events occurred, including the death of General Julius Quadratus Bassus during a campaign in Dacia and the need to manage unrest caused by the Sarmatians. Hadrian left Marcius Turbo, a Roman knight, in charge of Dacia and Pannonia Inferior, signaling a political rather than military emergency related to a conspiracy involving four consulars.

Hadrian's Second Journey

It began in 121 AD, after nearly three years of dedicating his time to Roman administration. His travels during this period took him to various parts of the western Roman provinces. The journey commenced on April 21 with the emperor celebrating the founding of Rome by inaugurating the construction site of the Templum Veneris et Romae. He then traveled to Gaul, visiting the Rhine armies and continuing into Raetia and Noricum before crossing over to Britain in 122.

"...both at Rome and abroad he always kept the noblest men about him" (69.7.3) is a reminder that a comitatus was with him on his travels".

Cassius Dio

In Britain, Hadrian focused on securing the northern frontier, accompanied by Platorius Nepos, who replaced Pompeius Falco. Afterward, Hadrian headed towards Spain, passing through Nemausus (modern Nîmes), where he ordered the construction of a basilica in honor of Plotina. Hadrian's stay in Spain was cut short due to tensions on the Euphrates frontier, with the threat of war with Parthia looming, and he left for the East, possibly visiting Cappadocia to strengthen the Roman defenses there.

One notable part of his second journey was a stop in Cappadocia where Arrian, a close ally of Hadrian, reported on several construction projects initiated by the emperor. These included improvements to altars, inscriptions, and a temple to Hermes, though many details of this visit remain obscure.

Hadrian spent the winter of 123/124 in Nicomedia before continuing his journey through various cities in Asia Minor, such as Cyzicus, Pergamum, and Smyrna. He eventually returned to Italy in 125, likely visiting Athens along the way, a city he greatly admired and often visited.

His travels to the provinces were not only to inspect military defenses but also to engage with provincial communities. The numerous statues and portraits of Hadrian found throughout the empire are evidence of the impact of his visits. These journeys solidified his image as a traveling emperor deeply involved with the provinces, in stark contrast to many of his predecessors.

His Third Journey into New Territories

After Hadrian’s travels to Syria and Egypt, documented by sources like Halfmann, (Helmut Halfmann, a scholar known for his extensive research and works on Roman emperors, particularly focusing on the travels and activities of emperors such as Hadrian), it was high time to visit Northern Africa.

In 128 CE, Hadrian, still heavily focused on maintaining Rome’s military power, set off on a short but significant journey to North Africa. His arrival in Carthage coincided with a miraculous turn of events: after five years of severe drought, the city experienced its first rainfall just as the emperor landed.

In gratitude for this favorable omen, the city was temporarily renamed Hadrianopolis. To further strengthen the region’s infrastructure, Hadrian ordered the construction of a new aqueduct, a much-needed addition to ensure a reliable water supply for Carthage and its surrounding areas.

From Carthage, Hadrian traveled inland to the important legionary base at Lambaesis in Numidia, located in modern-day Algeria. Lambaesis was the headquarters of the Third Legion Augusta, Rome’s primary military force in North Africa.

During his six-day visit, the legion staged an impressive series of military exercises to demonstrate their discipline and readiness. Hadrian was keen to assess the capabilities of his troops firsthand and ensured that this type of display was a common feature of his travels, as he sought to ensure that military standards were maintained throughout the empire.

On July 1, 128 CE, Hadrian addressed the assembled soldiers at Lambaesis, delivering a speech that praised their discipline and military expertise.

The Hadrianic legionary base of the Legio III Augusta, founded shortly before Hadrian's visit in AD 128, Lambaesis. Credits: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0

After his stay in Lambaesis, Hadrian continued his inspections, visiting an auxiliary cohort stationed at Zaraï on July 7. Zaraï was another key military site in Numidia, and Hadrian’s presence there was part of his ongoing efforts to oversee and strengthen Rome’s military defenses on the empire’s frontiers. He then proceeded to another unknown location, where he inspected another cohort. His tour of the African provinces complete, Hadrian soon returned to Rome by sea, having bolstered his legions’ morale and ensured that the region remained under firm Roman control.

Hadrian’s Fourth and Final Journey

In the last, and one of his largest trips, he traveled through various regions such as Gerasa, Jerusalem, where he founded the city of Aelia Capitolina, Gaza, and Alexandria. His journey also included a significant event on October 30, 130 AD, where he founded Antinoopolis in memory of his deceased companion Antinous. Following this, Hadrian spent the winter of 130/131 in Alexandria.

"He subjected the legions to very strict discipline ... and assisted the allied and provincial cities very generously. Indeed, he saw many of them-more than any other emperor".

Cassius Dio

From Egypt, he moved on to Athens, but before this, there were complex stops and gaps in his travels. While some sources, like Weber, suggested a trip along the eastern frontier to Trapezus in 131, this was refuted based on evidence from Arrian. Instead, Hadrian likely traveled along the coasts of Syria, Cilicia, Pamphylia, and Lycia, reaching Ephesus. The monumental gates in Lycian cities like Phaselis and Patara confirm his presence, particularly around the year 131.

Halfmann fills in the timeline with a possible European journey through Thrace, Macedonia, Moesia, and Dacia, citing inscriptions that mention Hadrian’s companion T. Caesernius Macedo. However, scholars debate the timeline and details of this journey, especially considering Macedo's career trajectory, which complicates dating the trip to 131.

Hadrian’s third winter in Athens (131/132) was marked by important milestones, such as the consecration of the Temple of Olympian Zeus and the founding of the Panhellenion. What followed after his time in Athens is less clear, with some sources placing him back in Rome by May 134, and others suggesting he could have been involved in the Bar Kokhba revolt in Palestine, which erupted in 132.

However, Halfmann doubts Hadrian's direct involvement in the conflict, noting the absence of the typical imperial phrase "I and the army are well" in Hadrian’s letters to the Senate. This omission hints at Hadrian's distance from the conflict during the revolt.

Hadrian did not immediately return to Rome after leaving Athens in 132. Instead, he spent the winter of 132/3 in a location close to Palestine, where he made preparations for the following year's military campaigns. It is assumed that during this time, he personally oversaw the strategies and movements of his generals.

Although the rebellion continued until 135, the year 133 is thought to have marked a turning point in quelling the uprising. Evidence from a military diploma suggests that by September 134, Hadrian had not yet received the formal acknowledgment of victory, or imperatorial acclamation, signifying the end of the conflict.

After making progress in 133, Hadrian found it more pressing to leave the scene of a failed policy than to return directly to Rome. The shifting circumstances of recent events had drawn him away from his usual civilian tours and towards pressing military needs. Instead of taking a quick sea journey, Hadrian turned his attention to Pannonia, where the northern border faced the Suebi and the eastern front the Sarmatians.

From there, he likely traveled along the main road through Sirmium and Siscia (or Poetovio) to reach Aquileia. Since a harsh winter in Pannonia was undesirable, Hadrian likely reached Rome towards the end of the year, completing his journey in a manner that was both practical and comfortable. (Journeys of Hadrian, by Ronald Syme)

It can easily be deducted that Hadrian is arguably the most traveled Roman emperor, and his frequent tours of the empire were a significant part of his administrative style. His journeys were driven not only by necessity but by a personal curiosity about the vast and diverse empire he governed. His extensive travels distinguished his reign and influenced his policies of consolidation, defense, and cultural patronage, marking him as a truly, unique leader.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: