Mare Clausum: How Romans Managed Extreme Storms, Floods, and Monsoons

Winter seas closed, rivers burst their banks, and rare “medicanes” raked the coast—yet Rome kept grain and shipping moving. The Empire had enforced weather rules, from mare clausum schedules and storm-proof ports to timed monsoon runs.

Although Ancient Rome was never witness to the deadly Atlantic hurricanes or Pacific typhoons, like the recent hurricane Melissa in Jamaica, Roman sailors and city builders lived with weather as a daily constraint. From November gales that closed sea lanes to spring floods that filled the Tiber’s embankments, the empire learned to schedule, engineer, and legislate around the Mediterranean’s moods.

Ancient writers speak of tempests and cloudbursts; archaeologists find breakwaters poured underwater; trade manuals time voyages to the pulse of the monsoon. Read together, these traces show a pragmatic system: reduce exposure, harden the edges, and move only when wind and water allow.

The “Closed Sea”: Calendars Against Risk

Roman navigation did not run on a modern timetable but on a weather one. Between late autumn and early spring, the long swell, shifting winds, and short daylight of the Mediterranean made blue-water crossings unreliable.

By late antiquity, Latin writers speak of a mare clausum, a season when open-sea sailing largely paused. That pause was not a blanket ban: cabotage could continue along coasts, and emergencies broke rules, but the default was caution. The logic was simple—most cargoes were not urgent enough to gamble the ship, crew, and annona.

Practical seamanship underpinned the calendar. Coastal pilots read wind roses and landmarks; grain convoys hugged lee shores; masters preferred dawn departures to judge sea state and light.

The “season” opened in late spring, widened through summer, and narrowed again by mid-autumn, with local winds and routes shaping the precise windows. The very idea of a “closed sea” was a risk budget: a shared understanding among shippers and officials that winter seas multiplied hazards, costs, and losses, so routine long passages should wait for fairer months.

Hardening the shore: concrete, moles, and storm basins

If winter seas were a reason to stay in port, ports had to survive winter. Roman harbour builders answered with moles, breakwaters, and basins designed to blunt wave energy. The decisive tool was hydraulic concrete—lime mixed with volcanic ash (pozzolana) that set in seawater.

Ancient technical writing describes how to cast such works: either by placing concrete within a flooded containment or by using cofferdams to pour foundations below the waterline. Archaeology tracks that recipe around the sea. Analyses from provincial sites show pozzolanic mortars—sometimes with ash shipped far from Italy—binding rubble into storm-resistant masses.

The method changed what could be built. Where pre-Roman engineers stacked large ashlar or rubble, Roman crews could pour monolithic bodies whose faces took the first blows of winter storm trains. At a minor harbour on Crete, surviving moles—now partly beneath a modern marina—retain pozzolanic mortars whose chemical signatures match Italian sources rather than local volcanic sands.

Coring at major hubs such as the Claudian and Trajanic basins at Portus, and at Anzio and Cosa, has extracted continuous sections of these masses, confirming standardized mixes and staged pours. The result was not just shelter for anchorages but a tougher, engineered coastline able to ride out seasonal extremes.

Riding it out: ships, tactics, and decisions at sea

Storm management at sea was a chain of decisions. Merchant hulls were broad-beamed for cargo capacity and built stoutly for hard service. Crews carried spare rigging, sea anchors, and long cables.

In rising winds, masters shortened sail, streamed drag to keep bows to the waves, or ran for known havens. Ancient narratives preserve the vocabulary of bad weather—sudden squalls, confused seas, dangerous rebounds from cliffed coasts—and the countermeasures: strike the main, lash the yards, heave to, lighten the ship by cutting loose deck cargo.

Even with skill, winter crossings multiplied hazards: gusts that outpaced square sails, sleet that iced lines, nights too long for safe coastal reckoning. That is why the sailing calendar mattered; when weather windows narrowed, prudent captains shifted from ambition to survival.

Writers investigating the causes of winds and storms add another layer: the Mediterranean’s winter pattern of mobile lows and strong gradients was keenly felt, even if ancient terminology was descriptive rather than diagnostic. Observers connected heavy rain with sudden river rises and contrasted the clean fair winds of summer with the squally, variable airs of late autumn. Seamanship worked around those realities.

When rivers rose: floods, embankments, and the Tiber’s management

Sea storms were only half the story. The other half lay inland—cloudbursts in the Apennines pushing the Tiber into Rome. The city lived with cyclical inundations that swamped low quarters, contaminated wells, and disrupted markets. Roman responses combined hydraulics and bureaucracy.

Magistrates and, later, imperial officials—the curatores alvei Tiberis—maintained channels, cleared obstructions, and managed embankments. Over time, quays and walls rose; islands and meanders were constrained; bridges with triangular cutwaters broke current.

Writers record damaging floods as political events, but archaeology and topography show a longer arc of adjustment: quarries supplying revetment stone, drainage works tied into the Cloaca Maxima, and periodic re-profiling after destructive years. Flood control never eliminated risk. Instead, it shortened recovery.

Markets reopened sooner when quays were faced and raised; debris moved more quickly when channels were maintained; bridge piers stood longer when hydrodynamics were taken seriously in their design. In a city built around a working river, this was the only sensible goal—keep the city working through its cycles and be ready to rebuild the moment water fell.

Working with the monsoon: Red Sea ports and the Indian Ocean

Far from the winter gales of the Tyrrhenian, Roman merchants on the Red Sea timed voyages to the heartbeat of the Indian Ocean monsoon. Sailing manuals and itineraries describe a summer departure with the fair southwest wind and a winter return on the northeast. That rhythm compressed risk.

A well-timed run from Egyptian ports to western India could be direct and fast; missing the window meant waiting months or fighting contrary winds along a hazardous coastal shuffle. The text known as the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea outlines ports, seasons, and cargoes in a way that only makes sense if skippers were exploiting repeatable seasonal winds across open water.

Archaeology at Berenike and Myos Hormos aligns with that schedule. Warehouses and berthing basins facing Egypt’s Red Sea fringe make sense as waypoints for fleets that moved in pulses, not trickles: load in Egypt, jump with the season across the open, and ride back when the winds turned.

The system delivered pepper, gemstones, and textiles with fewer weather surprises than a mid-winter slog across the Aegean. It was the same logic as the Mediterranean sailing calendar, applied to a different ocean with a larger, steadier heartbeat.

Policy, ports, and the cost of delay

Because weather could immobilize ships for months, the Roman state buffered volatility with ports and policy. Portus, the great artificial harbour north of the Tiber mouth, operated as a storm-season reservoir: long moles blunted wave energy; a hexagonal basin calmed water; canals linked sea and river so fleets could sit out bad months under supervision and then surge grain inland the moment seas eased.

The administrative side matched the concrete. Shippers tied to the grain supply enjoyed privileges and obligations; rules and contracts recognized winter closure implicitly by structuring duties, storage, and liability around the sailing season. The annona’s success depended on this choreography—ports as buffers, policy as ballast.

Evidence from harbour coring projects shows standardization across major hubs: staged pours, repeatable mixes, and engineered faces that survived heavy seas year after year. That investment in durable basins turned “waiting out the weather” from an economic disaster into a routine cost of doing business. When the season reopened, the system restarted at speed. (The Ancient Sailing Season, by James Beresford; Floods of the Tiber in Ancient Rome, by Gregory S. Aldrete; The Roman Maritime Concrete Study (ROMACONS): the harbour of Chersonisos in Crete and its Italian connection, by Christopher Brandon, Robert L. Hohlfelder, John Peter Oleson and Charles Stern; Rome, Portus and the Mediterranean, by Simon Keay; Sailing the Indian Ocean in Ancient Times, by Jean-Marie Kowalski; Natural Questions, by Seneca)

Medicanes: tropical-like storms in a Roman sea

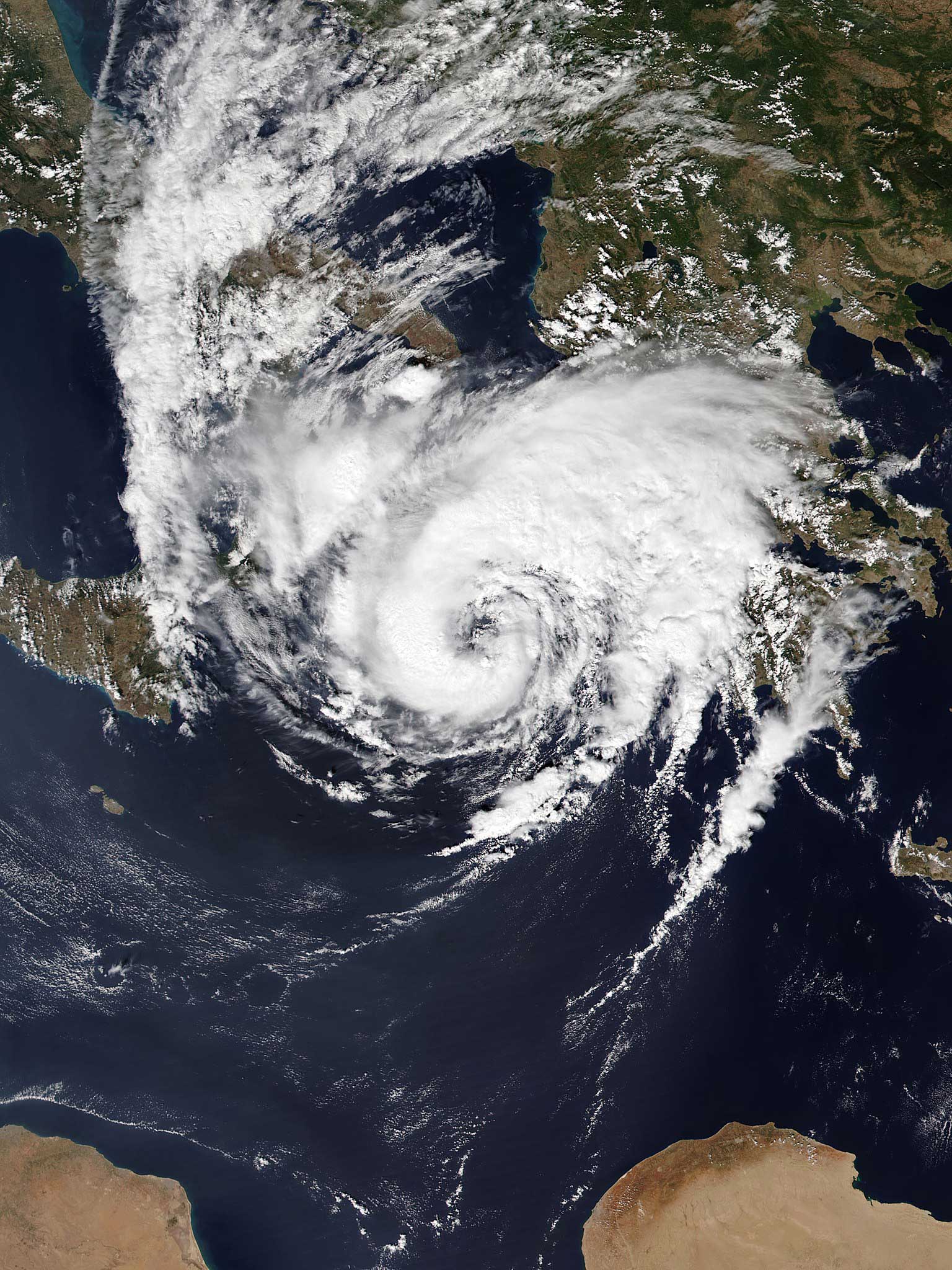

Modern meteorology identifies rare “Mediterranean hurricanes”—medicanes—as compact, warm-core cyclones that sometimes develop over the sea in autumn and winter. They are infrequent but intense, bringing gale winds and heavy rain, especially when interacting with mountain ranges and cold air intrusions. Ancient authors do not diagnose such systems explicitly, but the ingredients that form them existed then as now.

In practical terms, a late-season storm with a tight wind field and torrential rain would have been treated like any other severe low: harbours closed, ships sought lee, and coastal traffic paused. The rarity of medicanes aligns with the ancient habit of seasonal avoidance—another reason the winter sea was counted as largely “closed.” (Mediterranean Tropical-Like Cyclones (Medicanes), by Dr. Mario Marcello Miglietta)

Roman weather management was not mastery but choreography. Calendars rationed exposure; concrete and cutwaters reshaped edges; officials cleared channels; pilots watched the sky and the swell; merchants rode a planetary wind in and out of the Indian Ocean on schedule. In all of it, the principle held: accept what the weather offers, and build for what it takes away.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: