I Wash My Hands of This: Did Pontius Pilate Really Say It?

This iconic phrase echoes through centuries of art, faith, and cinema — but does history support it? A gesture remembered — but perhaps never made.

“I wash my hands of this.” The phrase echoes through centuries of art, literature, and liturgy — a symbol of moral detachment and reluctant authority. Attributed to Pontius Pilate during the trial of Jesus, it has become one of the most enduring lines in Western memory.

But did the Roman governor of Judea actually utter those words, or is this detail a literary creation? While the Gospel of Matthew describes Pilate performing this symbolic act before the crowd, no Roman historian — not Josephus, not Philo, not Tacitus — ever mentions it. To uncover the truth behind this moment, we must look beyond familiar verses and examine the Roman world Pilate inhabited, the politics he navigated, and the image later generations chose to preserve.

Appointed by Emperor Tiberius around 26 CE, Pontius Pilate served as the Roman prefect of Judea — a small but politically sensitive province within the sprawling Roman Empire. As an equestrian official, he was charged with maintaining order, overseeing tax collection, and enforcing Roman law in a land deeply resistant to foreign rule.

Based in Caesarea Maritima but present in Jerusalem during major festivals, Pilate governed a population divided by religion, class, and deep resentment toward Roman occupation. His rule, as recorded by Jewish historians such as Josephus and Philo, was marked by tension, violence, and a series of miscalculations that would ultimately lead to his recall.

Far from being a passive administrator, Pilate wielded his authority with a heavy hand — a man more feared than respected.

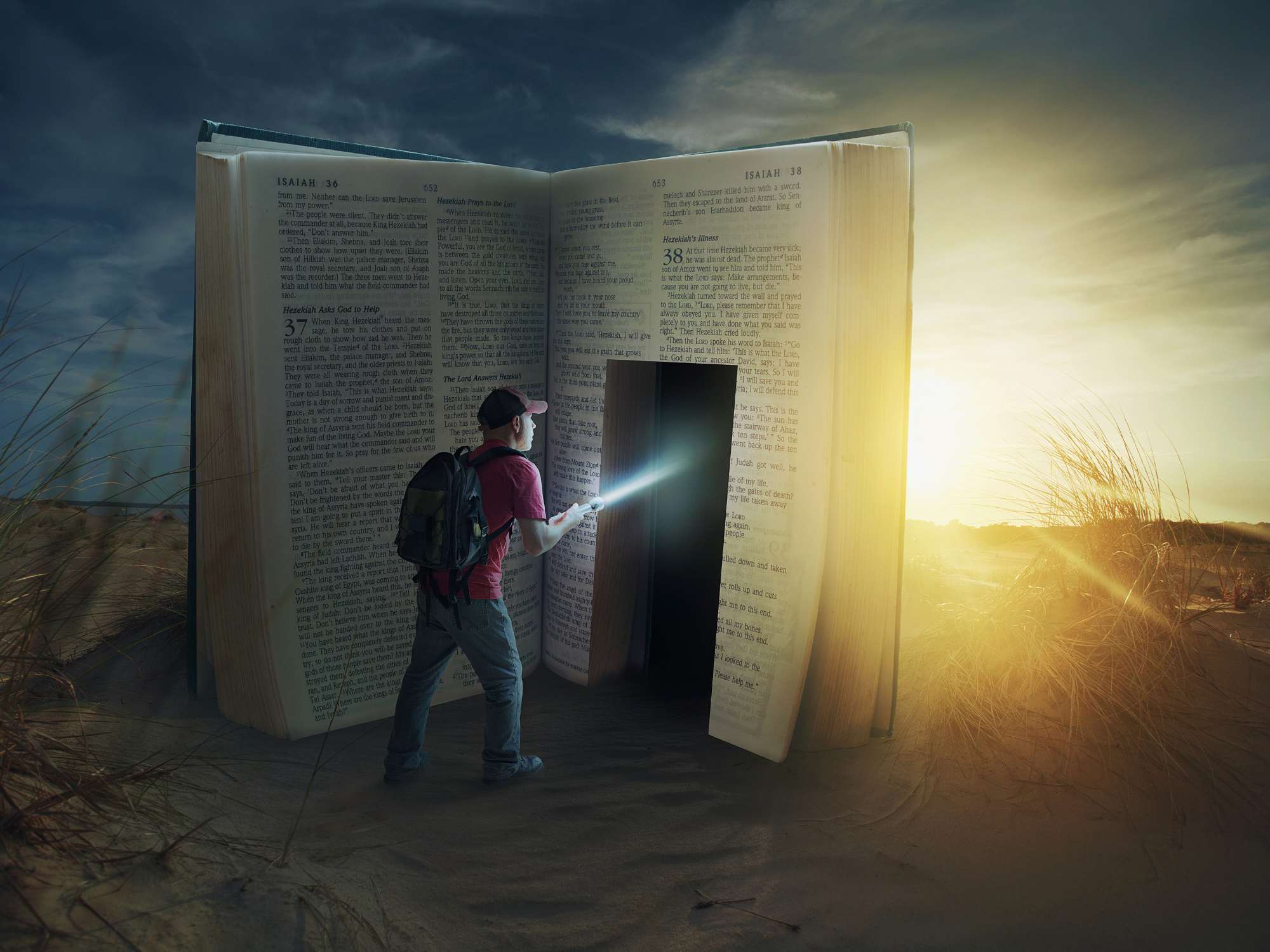

A painting by Mattia Preti,of Pontius Pilate washing his hands. Credits: The MET, CC0 1.0

Pilate in the Eyes of Jewish Historians: Josephus and Philo

Outside the Gospel narratives, two major Jewish historians of antiquity — Flavius Josephus and Philo of Alexandria — offer additional perspectives on Pilate’s rule in Judea. Their accounts, while shaped by their own cultural and political lenses, portray him not as a hesitant judge, but as a rigid and provocative Roman official, often indifferent to Jewish customs and prone to unnecessary violence.

In Jewish Antiquities, Josephus describes multiple incidents that inflamed local unrest. One of the earliest involved Pilate’s decision to bring Roman standards bearing the emperor’s image into Jerusalem by night — a move seen by the Jewish population as idolatrous. When a large protest formed in Caesarea, Pilate initially threatened mass slaughter but backed down only when demonstrators bared their necks in defiance:

“They threw themselves upon the ground and bared their necks, calling out that they would gladly die rather than see the laws of their forefathers transgressed…

Pilate, astonished at their steadfastness, ordered the images to be carried back to Caesarea.”

Josephus also recounts how Pilate used funds from the Temple treasury (korbanas) to build an aqueduct — triggering another protest in Jerusalem. This time, Pilate responded with undercover violence:

“He sent armed soldiers, disguised in civilian clothes, to mix with the crowd…

At a given signal, they attacked the protesters with clubs, many of whom perished under the blows or were trampled to death as they fled in panic.”

Philo of Alexandria, writing in Embassy to Gaius, echoes Josephus’ portrait but goes even further, painting Pilate as a symbol of imperial arrogance and cruelty. He describes him as:

“...a man of inflexible, stubborn, and cruel disposition, who executed people without trial, and was guilty of countless acts of violence and outrages upon the people.”

Philo also recounts the episode of the gilded shields — objects dedicated to Tiberius that Pilate installed in Herod’s palace in Jerusalem. Though they bore no image, their very presence in a holy city sparked public outcry. Pilate refused to remove them until a delegation of Jews appealed directly to the emperor, who ordered the shields taken down and relocated to Caesarea.

Taken together, these accounts reveal a man whose governance was harsh and politically clumsy, often insensitive to the religious sensibilities of his subjects. Pilate emerges not as the reluctant executor of Jesus’ death, but as a man already known for provoking unrest and responding with calculated — sometimes brutal — force.

The Civil Trial: Pilate, Rome, and the Power to Crucify

After the Sanhedrin passed a death sentence on Jesus, they were unable to carry it out themselves.

Thus, after condemning Jesus on the charge of blasphemy, they brought Him to the Roman governor, Pontius Pilate, and reframed their accusation in political terms to ensure Roman intervention.

Under Roman law, Jewish authorities were permitted to handle minor legal matters, but capital punishment was reserved for Roman jurisdiction. Any death sentence issued by a Jewish court had to be brought before the Roman governor, who could either uphold or overturn it. And so, Jesus was led to the judgment seat of Pontius Pilate, the Roman prefect of Judea.

Pilate, who had governed the province for several years, represented the authority of Imperial Rome. He ruled from Caesarea Maritima, a coastal city built in Roman style but traveled to Jerusalem during major festivals like Passover to oversee public order. There, he resided in Herod the Great’s former palace — a grand structure near the Temple, where official proceedings often took place in open air.

Pilate had a fraught relationship with the Jewish population. Known for his harshness and lack of sympathy toward their religious customs, he had repeatedly provoked unrest and was accused of corruption and brutality. On this occasion, Pilate met the Sanhedrin outside the palace, since they considered entering a Gentile residence during Passover defiling. From a raised platform near the palace’s front colonnade, the trial began, with Roman soldiers standing behind the governor, and the religious leaders presenting their prisoner.

Pilate immediately asked for the charges against Jesus. The Jewish authorities, perhaps hoping Pilate would simply confirm their judgment, replied vaguely:

“If he were not a malefactor, we would not have handed him over to you.”

But Pilate refused to rubber-stamp the decision.

“Take him and judge him according to your law,”

he said — a statement that forced them to admit, with resentment, that only Rome had the authority to carry out an execution.

Pressed to offer formal accusations, they advanced three claims: that Jesus incited the people, forbade paying taxes to Caesar, and claimed to be a king. Notably, they omitted the charge of blasphemy on which they had convicted Him, knowing Pilate would not entertain a theological dispute.

The second charge — that He opposed taxation — directly contradicted Jesus’ own teaching to “render unto Caesar.” The third accusation — that He claimed kingship — was deliberately framed in a political light to suggest sedition.

Pilate, skeptical of their motives, likely saw through their manipulations. He knew they delivered Jesus out of envy and possibly had prior knowledge of His teachings. Inside the palace, away from the crowd, he questioned Jesus directly:

“Are you the King of the Jews?”

Jesus responded carefully, asking whether this was Pilate’s own question or one passed along from others. Pilate, impatient, dismissed the nuance:

“Am I a Jew? Your own people have handed you over.”

Jesus then explained: His kingdom was not of this world. If it were, His followers would have fought to prevent His arrest. But His kingdom — a kingdom of truth — was different. Pilate, puzzled yet intrigued, asked:

“So, you are a king then?”

Jesus answered:

“You say that I am a king. For this reason I was born: to bear witness to the truth. Everyone who is of the truth listens to my voice.”

But Pilate, worldly and indifferent to spiritual matters, replied:

“What is truth?”

— not waiting for an answer. Though unconvinced by the charges and likely seeing Jesus as no political threat, Pilate returned to the crowd and declared:

“I find no fault in him.”

The Project Gutenberg eBook of "The Trial and Death of Jesus Christ: A Devotional History of Our Lord's Passion"

A Time of Handwashing: Pilate’s Gesture on Screen and Its Symbolic Weight

Christopher McDonough in “Pontius Pilate on Screen: Sinner, Soldier, Superstar,” explores the enduring impact of the prefect of Judea on cinematic imagination — and nowhere is this more vividly captured than in the recurring dramatization of Pilate’s most famous gesture: the washing of hands. Though drawn from a single Gospel verse (Matthew 27:24), this act has been magnified by generations of filmmakers as a potent symbol of moral ambiguity, powerlessness, and bureaucratic guilt.

In the 1927 epic King of Kings by Cecil B. DeMille, Pilate’s handwashing becomes an orchestrated ritual. A servant brings a basin and pitcher, and as Pilate ritually cleanses himself, the background displays a Roman eagle — an unmistakable emblem of imperial authority. His gestures — toward Christ, then Caiaphas, then the crowd — dramatize a transfer of responsibility, culminating in a symbolic X formed by Roman and Jewish actors parting ways. This visual geometry not only marks a moment of theatrical absolution but also underscores the political theatre of the scene.

More intimate portrayals continue this tradition. In Day of Triumph (1954), Pilate, played by Lowell Gilmore, washes his hands abruptly and hurls down the towel in irritation — a gesture of petulance rather than repentance. In Barabbas (1961), Pilate (Arthur Kennedy) performs the act in a public forum, only for Barabbas to mirror the motion at a nearby fountain. This doubling suggests a shared complicity: one man orders death, the other escapes it — but neither walks away unstained.

McDonough’s epilogue, fittingly titled A Time of Handwashing, reflects on how this ancient moment has been reinterpreted in modern contexts. From pandemic satire in The Babylon Bee — which jokes that Pilate didn’t scrub long enough to avoid divine judgment — to the omission of the gesture in Jesus of Nazareth, where Pilate’s decision stands bare and unceremonious, the act continues to evolve. Whether included or left out, it draws attention to the timeless struggle between power, responsibility, and conscience.

Across portrayals, Pilate’s hands — washed, unwashed, or trembling — remain a canvas on which filmmakers, theologians, and viewers project their own questions about guilt and evasion. McDonough’s study shows that this one small ritual, performed in the open air of Roman justice, echoes louder than many speeches — not for what it resolved, but for what it revealed.

Pilate’s Role in the Gospels: Historical Governor or Theological Figure?

Stephen Liberty’s “The Importance of Pontius Pilate in Creed and Gospel” (The Journal of Theological Studies, 1944) gives us an extensive analysis of the question asked. The striking image of Pontius Pilate washing his hands before the crowd — declaring:

“I am innocent of this man’s blood”

— is recorded only in the Gospel of Matthew. While often taken at face value, many scholars argue that this gesture was not a historical Roman custom, but a theological construct. In his article, Stephen Liberty makes the case that Pilate’s entire portrayal in the Gospels — and his enduring presence in Christian creeds — is deeply symbolic.

Far from a passive figure in history, Pilate becomes, in the Christian imagination, a paradoxical tool of divine justice and injustice: a Roman governor exercising earthly authority while unknowingly fulfilling a divine plan. Liberty notes that Pilate’s inclusion in the early creeds (“suffered under Pontius Pilate”) was not meant to date the crucifixion, but to highlight a theological truth — that the Son of God was judged and condemned by the representative of the greatest earthly power.

This had profound rhetorical weight, especially when preaching to the Jewish diaspora, as it explained how the Messiah’s rejection by his own people became the moment when salvation opened to the Gentiles. The trial scene, then, becomes a narrative fulcrum: a moment when Jew and Gentile unite, paradoxically, in the condemnation of Christ, fulfilling the Redeemer’s role in exposing human sin.

In this framework, the handwashing scene functions not as a Roman legal formality — for which there is no parallel in Roman sources — but as a deliberate literary gesture. It echoes Jewish purification rituals (see Deuteronomy 21:6–9), thus resonating with Matthew’s Jewish-Christian audience, while simultaneously illustrating Pilate’s attempt to distance himself from a sentence he himself would ultimately carry out.

As Liberty observes, the Gospels are not modern histories but theological texts, shaped by the early Christian community’s need to interpret suffering, rejection, and redemption. Pilate’s gesture, therefore, becomes a dramatic symbol of moral evasion and the collision of earthly rule with eternal truth.

In Liberty’s view, the handwashing — like Pilate’s name in the creeds — serves a dual function: it condemns the injustice of secular power and dramatizes the tragic irony of a man who, faced with truth incarnate, chooses the path of caution and ambiguity. By embedding Pilate into the passion narrative and Christian memory, the Gospel of Matthew offers a powerful meditation on how divine purpose unfolds even through political weakness, ethical failure, and ritualized innocence.

The Man Behind the Gesture

As the Roman prefect of Judea, Pontius Pilate held the highest authority in the province, responsible for maintaining order and executing justice on behalf of the empire. Yet, when confronted with the case of Jesus of Nazareth, Pilate revealed himself to be a man caught between power and pressure, law and expediency.

Historical analyses, such as the one in Michael Nthuping’s “The Characterisation of Pontius Pilate in the Four Gospels,” depict Pilate as a figure of contradictions: shrewd enough to recognize Jesus’ innocence, but politically vulnerable enough to yield to public outcry.

Without immediate military support during his early years in office, Pilate had to rely on delicate cooperation with the local Jewish elite — a reality that may have influenced his decision to appease the crowd. His reluctance to condemn, his philosophical detachment (“What is truth?”), and his symbolic distancing from guilt — captured most vividly in the Gospel of Matthew’s handwashing scene — all point to a man struggling to preserve authority while relinquishing responsibility.

In the end, Pilate’s gesture, whether historical or literary, reflects a universal temptation: to claim innocence while enabling injustice. And in that quiet moment at the edge of history, Pontius Pilate became not just a Roman governor, but a mirror for power itself.

In that moment, as water trickled through Pilate’s fingers, history slipped through them too.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: