Herodes Atticus: A Bridge Between Greek Heritage and Roman Power

Herodes Atticus is a fascinating figure, especially in the context of his relationship with the Roman Empire. A Greek aristocrat from Marathon, Herodes was born into immense wealth and became one of the most prominent benefactors in the Roman Empire during the second century AD.

Herodes Atticus, (Lucius Vibullius Hipparchus Tiberius Claudius Atticus Herodes) was Greek by heart and Roman by honor. An extraordinarily wealthy Athenian, renowned sophist, generous benefactor, and eventually a Roman senator and consul—was a controversial figure even in his own time. He was entangled in numerous disputes with other wealthy individuals, including rulers, and had complex, often strained, relationships with his fellow Athenians.

Born with a Silver Spoon in the Mouth

Herodes Atticus, was born into a complex legacy of wealth, political tension, and cultural duality. His grandfather, Hipparchus, one of the wealthiest men in the Roman Empire, was accused of tyranny by Emperor Domitian, leading to the confiscation of his vast fortune—and possibly his life.

This left Herodes’s father, Atticus, to live in relative obscurity until a fortunate discovery. Around the accession of Emperor Nerva, Atticus uncovered a hidden family treasure, which allowed him to reclaim both wealth and influence. He joined the Roman Senate and, through a series of prestigious roles, restored his family’s stature.

From an early age, Herodes received an exceptional education designed to prepare him for public life. As was typical of Greek elites, his early education focused on grammar and foundational subjects, but Atticus spared no expense when it came to his son’s higher education.

Herodes was exposed to a blend of Greek and Roman influences, even staying with prominent Roman senators to gain fluency in Latin and an understanding of Roman culture. His father saw to it that he trained in rhetoric, a skill that was not only prized among Roman aristocrats but also vital for navigating the complex world of imperial politics.

Herodes, the Orator

His journey in public speaking was not without challenges. While still a young man, he traveled to the Danube to address Emperor Hadrian on behalf of Athens’ youth, only to freeze mid-speech. This public failure strained his relationship with his initial tutor, Secundus, and spurred his father to hire renowned rhetoricians, including Scopelian, who helped Herodes master extemporaneous oratory—a crucial skill in Greek and Roman society.

This training allowed Herodes to shine as a speaker.

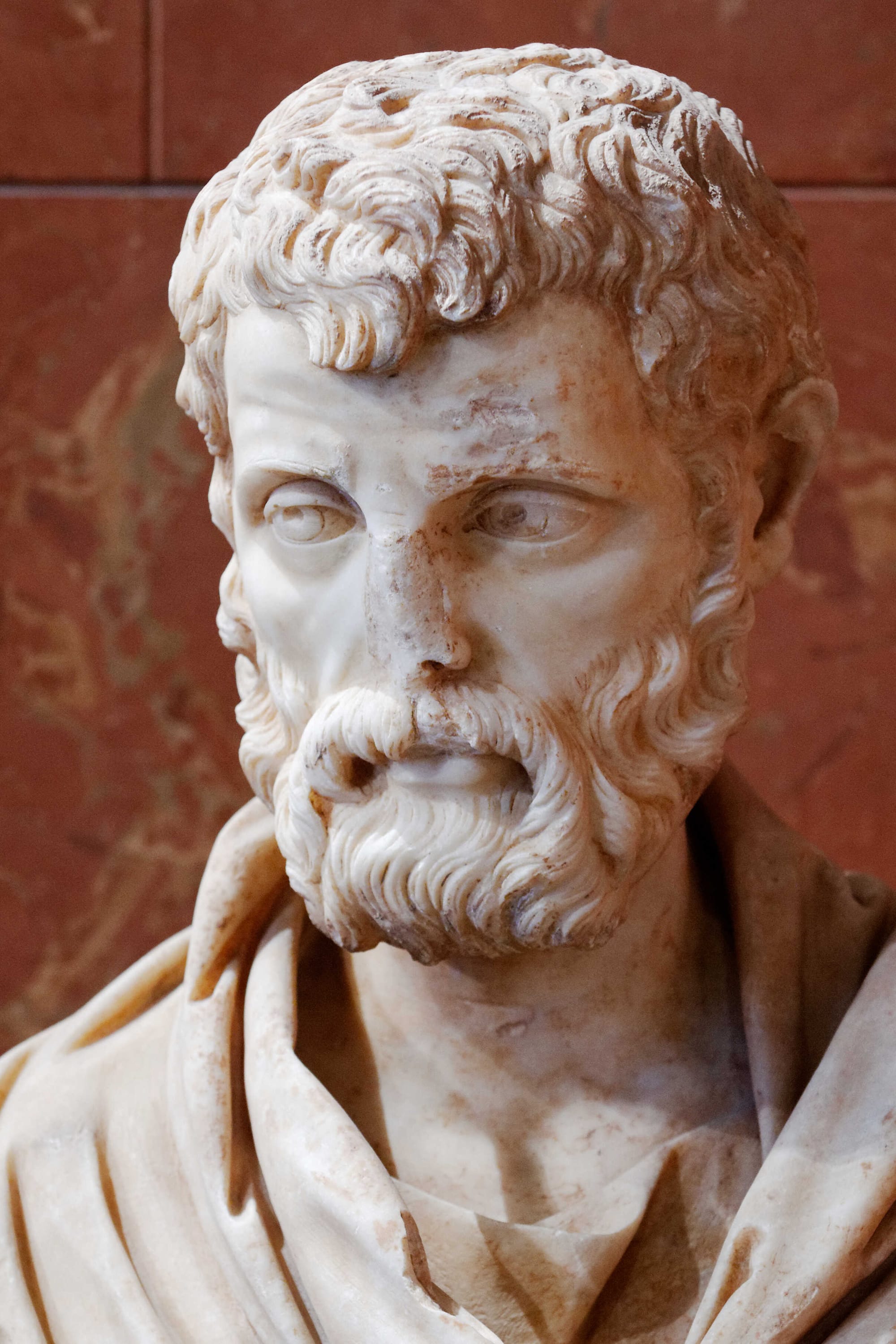

Bust of Herodes Atticus at the Louvre. Credits: Marie-Lan Nguyen, CC BY 3.0

Herodes embodied the duality of Greek and Roman identities. Deeply rooted in Greek intellectual traditions, he was also a respected figure in Roman circles, blending Greek cultural pride with the Roman political prowess he had cultivated. His friendships with influential figures like Favorinus, who left him a house and library in Rome, further solidified his role as a bridge between Greek heritage and Roman authority.

His rhetorical talent, wealth, and connections enabled him to influence both Greek and Roman elite circles. His life, marked by public triumphs, intellectual pursuits, and cultural contributions, established a legacy that reflected his ability to navigate—and thrive within—the worlds of Greece and Rome.

Herodes Atticus, was often called orator nobilissimus of the Second Sophistic—a second-century rhetorical movement— and is recognized for his prominence, though he isn’t considered a major historical figure. Despite no surviving works by Herodes, his life story gained enduring attention thanks to Philostratus, who depicted him in Vitae Sophistarum, captivated by his diverse life and vast architectural philanthropy, like the Odeum in Athens.

Herodes was a wealthy benefactor who cultivated the Attic rhetorical style, but past studies have mainly shown him as a distant figure, noting his talent and wealth without exploring his personal connections or influence in the Antonine era. (Herodes Atticus: An Essay on Education in the Antonine Age, by A. J. Papalas)

Climbing the Steps of Athenian Power

From a young age, Herodes, spent time in Rome, staying with Publius Calvisius Tullus Ruso, the consul of 109 AD and grandfather of the future emperor Marcus Aurelius. This time in Rome, where he likely learned Latin and Roman customs, prepared him for a future in public service. His father also introduced him to Athenian society early on. In 125, Herodes took his first public role as agoranomus in Athens, a position often reserved for young men from influential families to help launch their political careers.

His appointment as agoranomus coincided with Emperor Hadrian’s visit to Athens, which required the city to boost supplies—a task well-suited for Herodes, the son of one of Athens' wealthiest citizens. His performance likely met expectations, as he quickly advanced to the role of eponymous archon in 126/7, a more prestigious position.

Following his success in Athens, he shifted his career to Rome, where he served successively as quaestor, tribune of the plebs, and praetor. By the 130s, he took on the role of corrector of the free towns in the province of Asia, marking his prominence in Roman governance. (Herodes Atticus and the Athenians, by Marcin N. Pawlak)

Herodes Atticus’s Role in Shaping the Greek-Roman Legacy

Herodes Atticus was a unique figure, standing out due to his wealth, eloquence, and confidence, which allowed him to push the boundaries of conventional behavior. As a Greek who achieved the rare status of Roman consul and married a Roman patrician, he embodied both Greek and Roman identities in a period where these cultural distinctions mattered.

Although Greece had long been under Roman rule, the Greek language and traditions persisted, and labels like “Greek” and “Roman” were used to classify and distinguish people. Despite his wealth and high status, Herodes might still be looked down upon in a Roman courtroom as a “Greekling,” reflecting how these identities could still carry stigmas at the upper reaches of society.

Herodes’ Greek identity was strong, his family claimed descent mythological figures such as Herakles, Kekrops, Theseus and Hermes, plus kinship with prominent Greek figures as the Athenian general Miltiades and Kimon. He also displayed Hellenic pride through his lectures, reinforcing the cultural pride of his audience.

Yet, his background included deep Roman ties. His mother’s family was from the Roman colony of Corinth, and his ancestors had forged connections with Rome for generations, including mentorships and priesthoods that gained them Roman citizenship. Marriage was another point where Greek and Roman elements intersected in Herodes’s life. His father’s marriage into the Vibullii family of Corinth marked an early tie with Roman citizens.

However, Herodes’s marriage to the Roman patrician Regilla was especially rare, as intermarriage between Greek and Roman aristocrats was unusual.

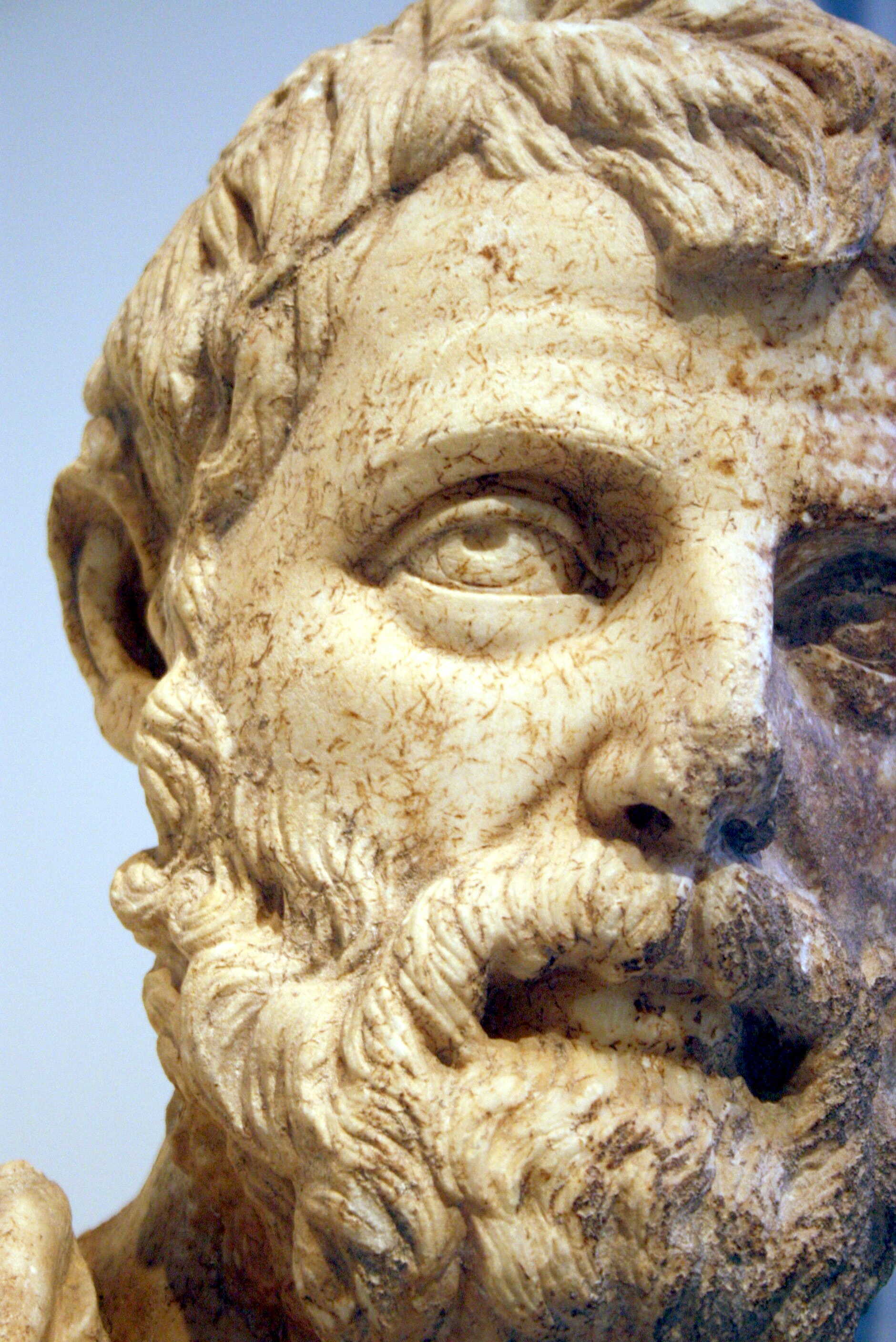

Bust of Herodes Atticus in Athens Archaeological Museum. Credits: G.dallorto

Herodes’s marriage to Regilla represented a unique blend of Greek and Roman elements, and some of the structures they built together symbolized their cultural union, especially after Regilla’s death when Herodes added inscriptions to honor her memory. Herodes’s career also spanned both cultures. He rose through the Roman ranks, becoming consul ordinarius at a young age, as aforementioned, and held various prestigious roles.

In Greece, he served as agoranomos (mentioned above) and eponymous archon in Athens, and contributed financially to the Panhellenion games. His education, likewise, was bicultural. He trained in the Greek rhetorical tradition in Athens and Sparta, but also spent part of his childhood in a Roman household, where he became well-acquainted with Roman customs. Through his career, marriage, and contributions to both Greek and Roman life, Herodes Atticus embodied a complex identity shaped by the fusion of Greek heritage and Roman influence, reflecting the intertwined yet distinct cultural worlds of his time.

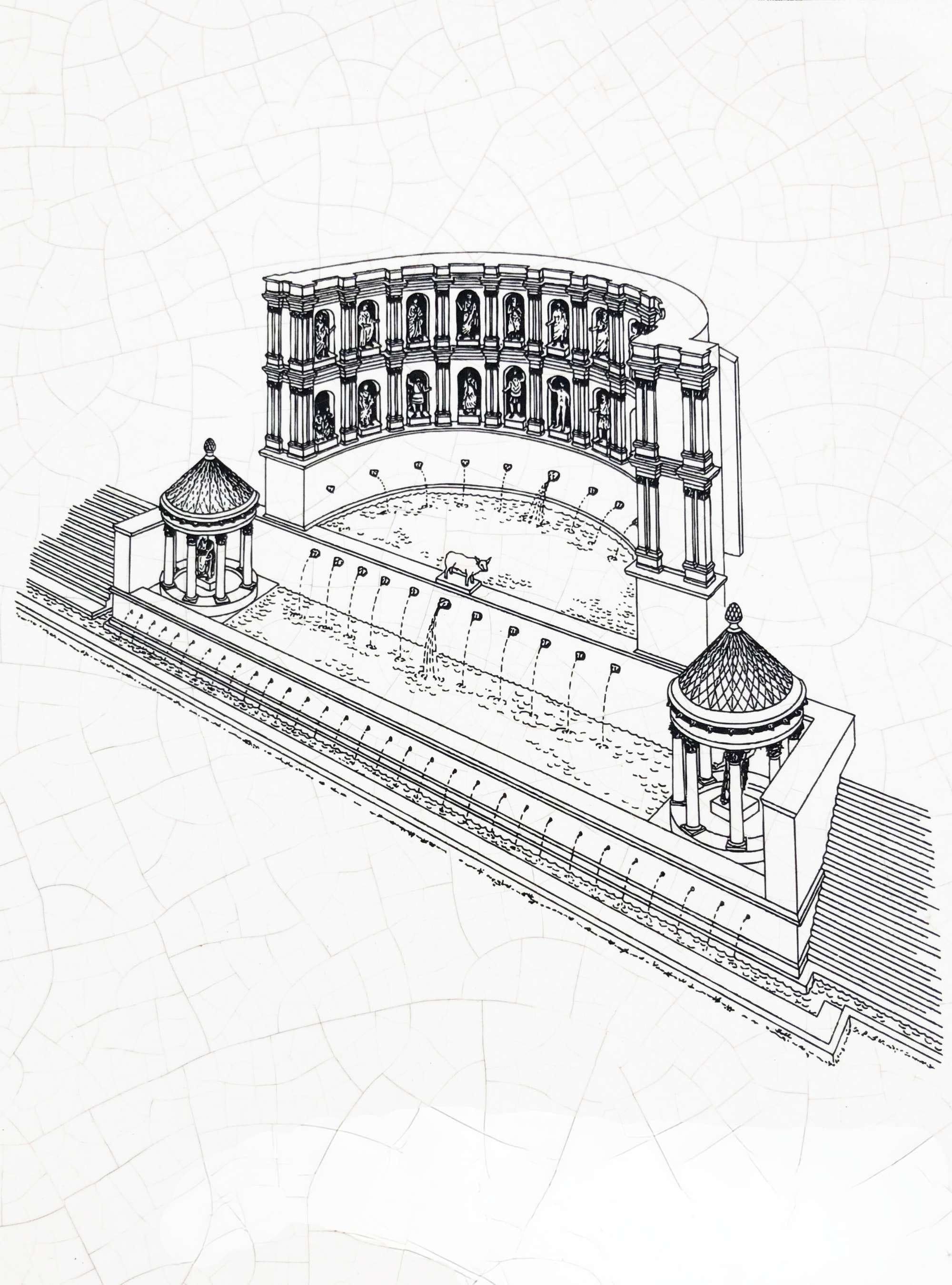

The Nyphaeum

Herodes Atticus and his wife, Regilla, constructed the Nymphaeum at Olympia, a monumental fountain decorated with statues that celebrated their combined Greek and Roman heritage. The statues of their family, positioned above the imperial family, showcased a layered form of self-presentation and status. Wealthy patrons like Herodes often engaged in public projects as a means of self-representation, and the Nymphaeum’s design made this dynamic explicit.

It was built during a high point in their lives: Herodes was a well-established figure, having served as a tutor to the emperor, married Regilla, and achieved the position of consul ordinarius. Regilla held a prestigious role as the priestess of Demeter, integrating her into Hellenic traditions while distinguishing her as a Roman woman with unique privileges.

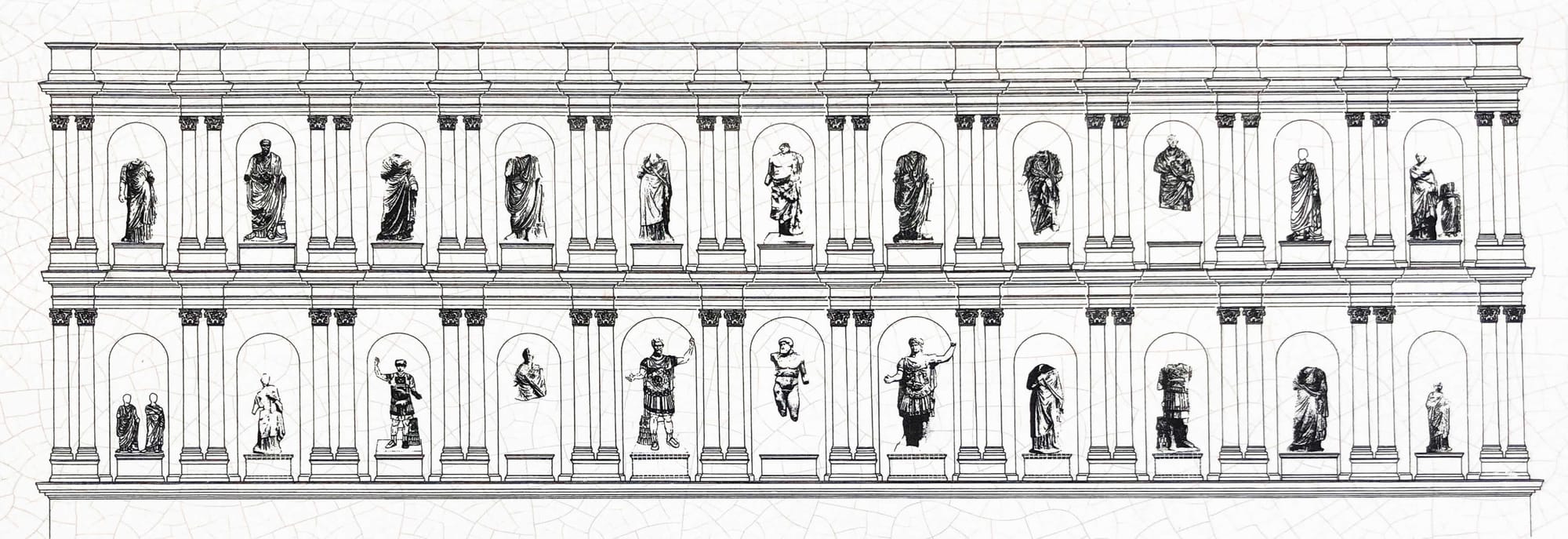

The Nymphaeum’s design used symmetrical arrangements to signify harmony between Greek and Roman elements. Statues of the imperial family occupied the lower tier, while the upper tier included members of Herodes and Regilla’s family. This arrangement implied a parallel status between their family and the emperor’s, suggesting a unity between aristocratic and imperial roles. At the center stood Zeus, flanked by statues of Regilla and Herodes, with other family members in balanced positions on either side.

The Nymphaeum, though harmonious, subtly maintained distinctions between Greek and Roman identities. For example, Herodes wore Greek attire in his statue, suggesting parity with his Roman family members without losing his Greek heritage. The Nymphaeum’s dedication, inscribed in Regilla’s name, highlighted her role as priestess of Demeter, while the statues of the imperial family below were dedicated by Herodes, showing a shared influence in the project.

While public reactions are not fully known, the philosopher Peregrinus voiced criticism, arguing that Herodes’ integration of Roman engineering into a Greek sanctuary weakened Greek identity by symbolically “feminizing” the Greeks, suggesting they were becoming too dependent on Roman luxury.

After Regilla’s untimely death, Herodes commissioned memorial structures for her that reinforced their cultural union and commemorated her impact on his life. These installations were modified with inscriptions that reflected their marriage’s posthumous significance, blending Greek and Roman cultural symbols and suggesting a sense of enduring unity even after her passing. These memorials, like the Nymphaeum, used balance and symmetry to navigate the complexity of Herodes’ bicultural identity, showcasing how his life intertwined both Greek and Roman elements in a sophisticated, symbolic manner.

1. Emperor Marcus Aurelius

2. Elpinike, daughter of Herodes Atticus

3. Emperor Hadrian

4. Man in a himation of the Dresden Zeus

5. Regilla (probably), wife of Herodes Atticus

6. Regillus, younger son of Herodes Atticus

7. Athenaides (probably), daughter of Herodes Atticus

8. Empress Faustina the Younger

9. T. Claudius Atticus, father of Herodes Atticus

Credits: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0

The Arch at Marathon

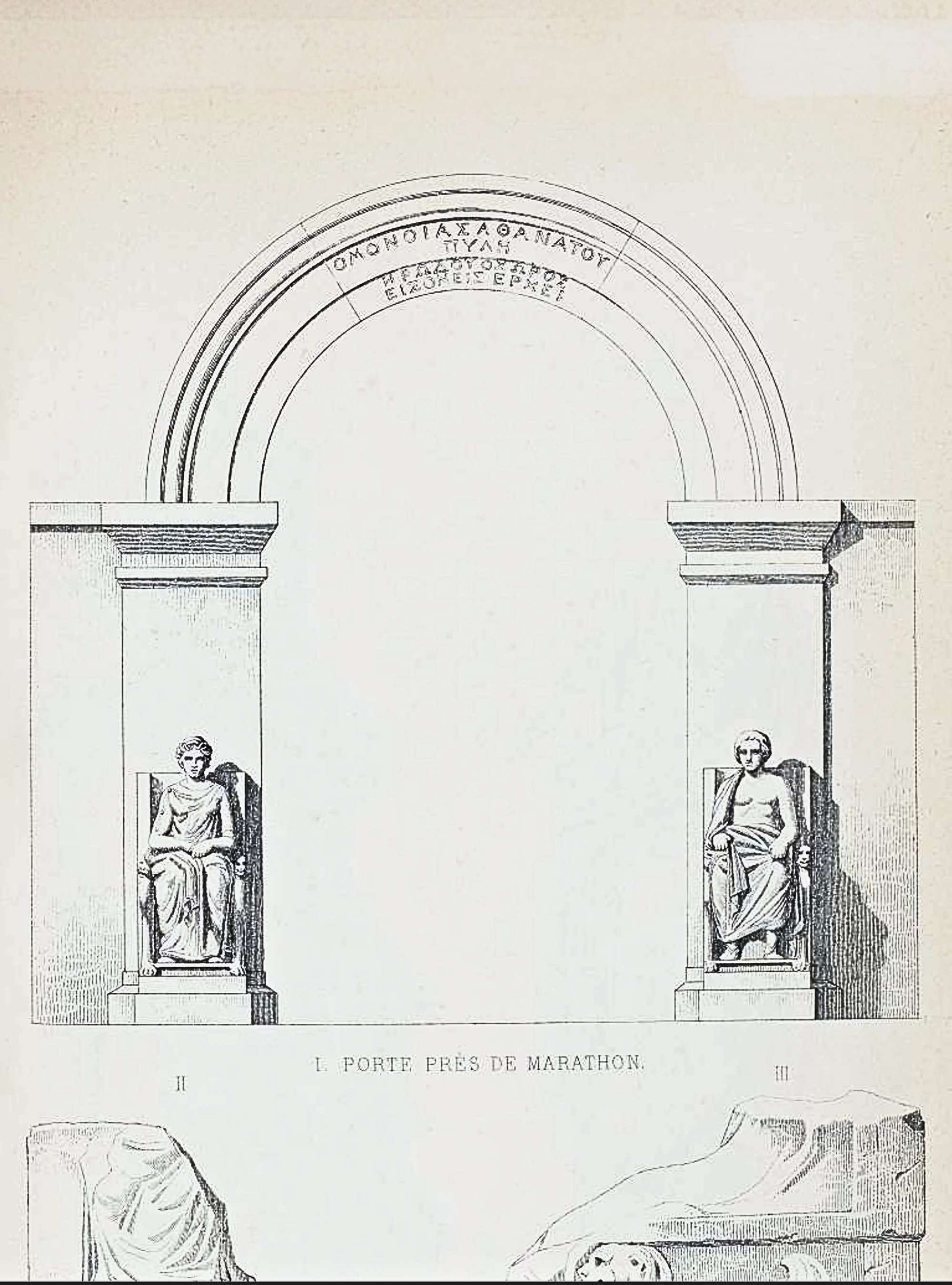

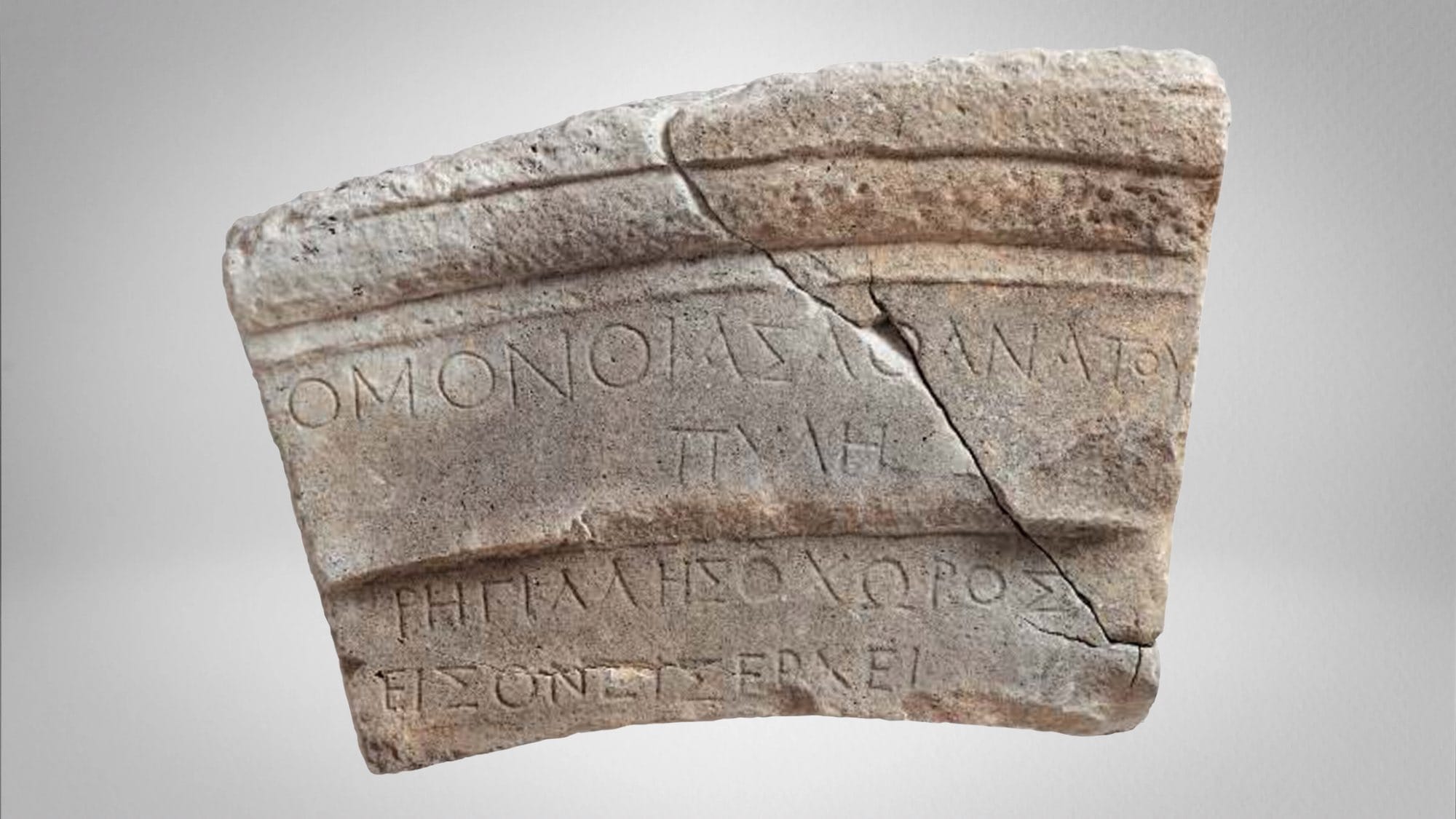

Herodes Atticus built an arch on his estate at Marathon, initially serving as an entry to a walled enclave. The arch featured symmetrical inscriptions on each side: one side read, "The Gate of Immortal Concord. You are entering Regilla’s area," while the other read, "Gate of Immortal Concord. You are entering Herodes’ area." This honorific structure was unusual for a private residence, as Roman emperors themselves rarely erected such arches for personal honor.

The arch’s design mirrored Hadrian’s arch in Athens, which also had dual inscriptions referencing Theseus and Hadrian to distinguish Greek from Roman. Herodes’s arch subtly emphasized the Greek and Roman duality of his and Regilla’s identities, suggesting a symbolic passage between their respective cultures.

The phrase "Immortal Concord" on the arch aligned with imperial messages of marital harmony, such as those seen in the matrimonial imagery of Antoninus Pius and Faustina. This initial phase of the arch thus connected the couple’s unity to broader imperial values.

However, Regilla’s sudden death, (In 160, during the year her brother served as consul, Regilla, eight months pregnant, was violently kicked in the abdomen by Alcimedon, a freedman of Herodes Atticus. This assault caused her to go into premature labor, resulting in her death) disrupted this portrayal of harmony.

Herodes’s grief was profound and public, marked by gestures like redecorating his home in black and commissioning a grand auditorium in her memory. Some viewed these acts as extravagant, suspecting him of trying to dispel guilt, though others defended his innocence.

Following Regilla’s death, Herodes subtly altered the Marathon arch. He added a new verse inscription on the eastern pillar, modifying its original meaning to reflect his loss. This addition, inscribed at eye level, was a private act of commemoration that quietly transformed the arch into a lasting symbol of his mourning and the complexity of his bi-cultural identity.

“Ah, blessed is he who has built a new city, 64 calling it by Regilla’s name; he lives in exultation.

But I live in grief because my dwelling has been built without my beloved wife, and my home is half-complete.

For the gods, in truth, when they have mixed the cup of human life, pour out joys and griefs as neighbors side by side.”

With the addition of Herodes’ inscription, the arch at Marathon was transformed into a commemorative monument, marking not only the boundary between male and female or Greek and Roman identities but now symbolizing the threshold between life and death. The poem inscribed on the arch uses architectural imagery—phrases like ἔδειµε νέην πόλιν (“he built a new city”), οἰκία τέτυκται (“a house has been made”), δόµος ἡµιτελής (“half-complete house”), and γείτονας (“neighbors”)—to express Herodes’s inner fracture after Regilla’s death.

The poem’s structure also reflects different layers of Herodes’s experience: temporally, it spans past, present, and eternity; logically, it follows a thesis-antithesis-synthesis pattern; and emotionally, it moves from joy to sorrow to a Homeric acceptance of fate. Herodes speaks in the third person in the opening line, “Happy is he,” before shifting to the personal lament, “I live in grief.” This change in perspective emphasizes the chasm between Herodes’s joyful past and his sorrowful present, as if he were now a different person entirely.

The Homeric allusions in the poem, particularly to The Iliad’s reference to Protesilaus, who died leaving his “house half-complete.” This parallel compresses life’s before and after, much like Herodes’s poem, using similar phrasing to reflect on loss and the unfinished nature of life after Regilla’s passing.

The Homeric phrase δόµος ἡµιτελής (meaning “half-complete house”) was a phrase often debated by sophists and likely resonated deeply with Herodes Atticus, reflecting the inner sense of division and incompleteness he felt in his grief. This feeling of “splitting” may have existed even before his bereavement, as he embodied both an intensely Greek identity and a bi-cultural one. His marriage to Regilla, meant to unite these dual identities, had now been severed.

Herodes’s use of this Homeric allusion also introduces a poetic reversal of gender roles. By associating himself with Protesilaus’s wife, he subtly aligns his grief with hers, possibly showing familiarity with interpretations of this story in Latin literature, such as in Catullus 68, where Catullus likens his own devotion to that of Protesilaus’s wife. Given Herodes’s Roman connections, it’s possible he knew Catullus’s work.

Initially, the arch at Marathon marked spatial and gender divisions—a gateway into Regilla’s private enclave within Herodes’s estate. After her death, however, it took on additional meanings. The inscription symbolized a break in time (before and after Regilla’s death), a reversal of traditional gender roles through his grieving process, and the loss of unity that the arch had once represented, echoing a rupture within himself that could no longer be reconciled.

The Triopion

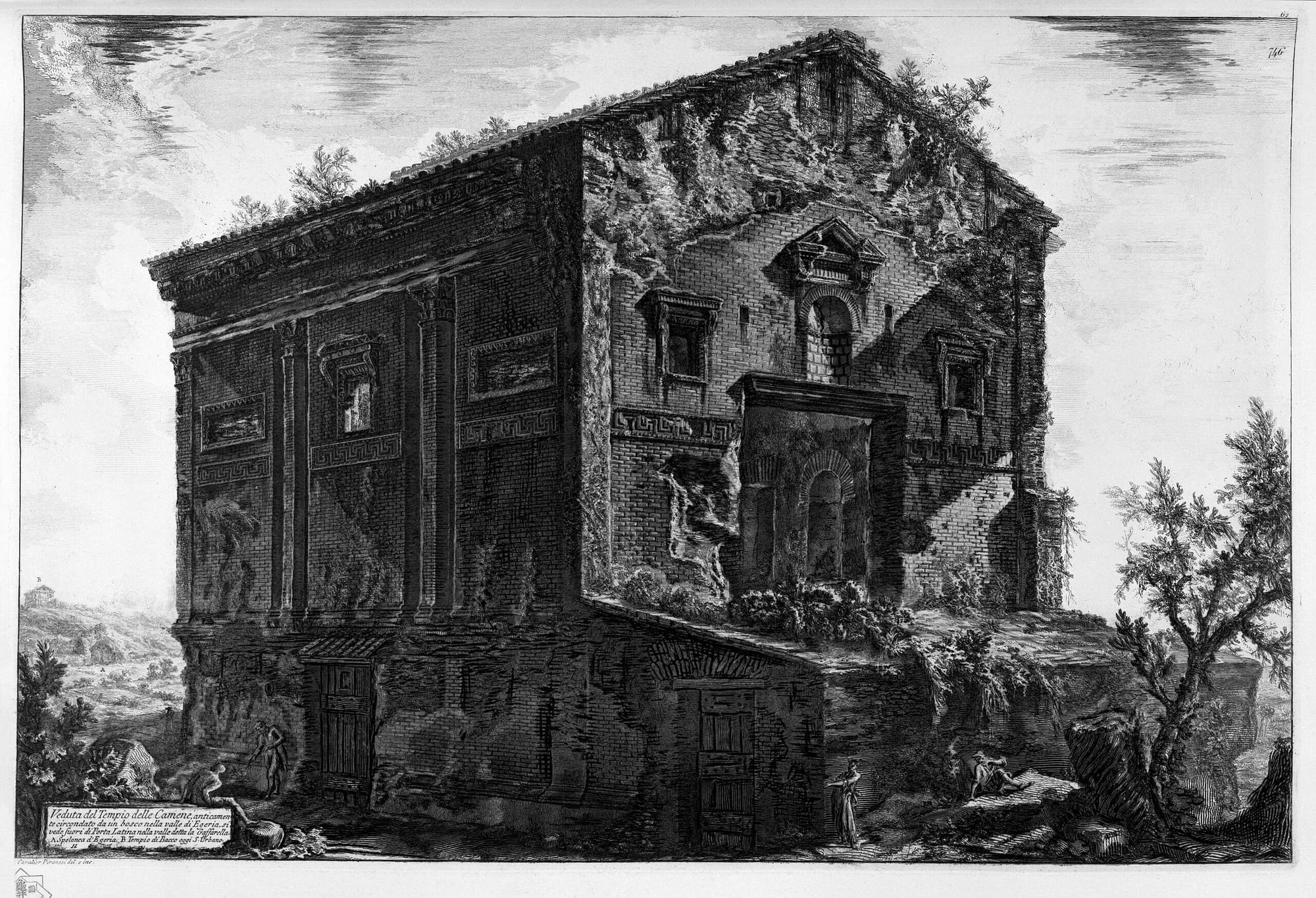

The Triopion was a complex of buildings and gardens along the Appian Way, three miles from Rome, likely inherited from Regilla’s family. The name “Triopion,” however, reflects Greek origins, (named after Triopas, King of Thessaly) resembling the sanctuary of Demeter at Knidos.

It was initially designed as a shrine to Demeter and the deified Faustina, with twin columns at the entrance dedicated to “Demeter, Kore, and the Chthonic deities.” An inscription on these columns warned against vandalism, suggesting this structure marked the entrance to the sanctuary.

The Triopion’s development occurred in two phases. Initially, it served as a bicultural shrine, housing statues of both Demeter and Faustina, who represented “Old and New Demeter.” After Regilla’s death, Herodes expanded the shrine to commemorate her by adding her image.

Conceptually, the precinct symbolized the union of Greek and Roman identities, akin to Regilla’s estate in Marathon but in reverse: a space dedicated to a Greek goddess on Roman land. Statues of caryatids, some dressed in Greek attire and others in Roman, adorned the sanctuary, further emphasizing this blend of cultures.

The choice to honor Faustina alongside Demeter may have been rooted in genealogy, as both Regilla and Faustina belonged to the Annii family. The shrine also drew on the established connections between Demeter and her Roman counterpart, Ceres—a link used in the past to symbolize Greek and Roman unity. Regilla’s role as a priestess of Demeter and Herodes’s involvement in the Eleusinian sanctuary reflected their shared devotion to the goddess. Establishing a new Demeter sanctuary in Italy was unusual, as this practice was typically reserved for emperors.

After Regilla’s death, Herodes honored her by incorporating her into the Demeter ensemble at the Triopion, aligning her with both “Old” and “New” Demeter. Demeter’s association with transitions, like marriage and the boundary between life and death, made the goddess an apt figure to symbolize Regilla’s identity.

Although Regilla was buried in Athens, Herodes commemorated her in Italy as well, likely in line with aristocratic Roman customs of having memorials on estates. The Triopion’s location along the Appian Way, near aristocratic memorials like that of Caecilia Metella, added significance, with Herodes possibly drawing inspiration from Claudia Semne’s nearby shrine, which also featured statues of the deceased in divine forms.

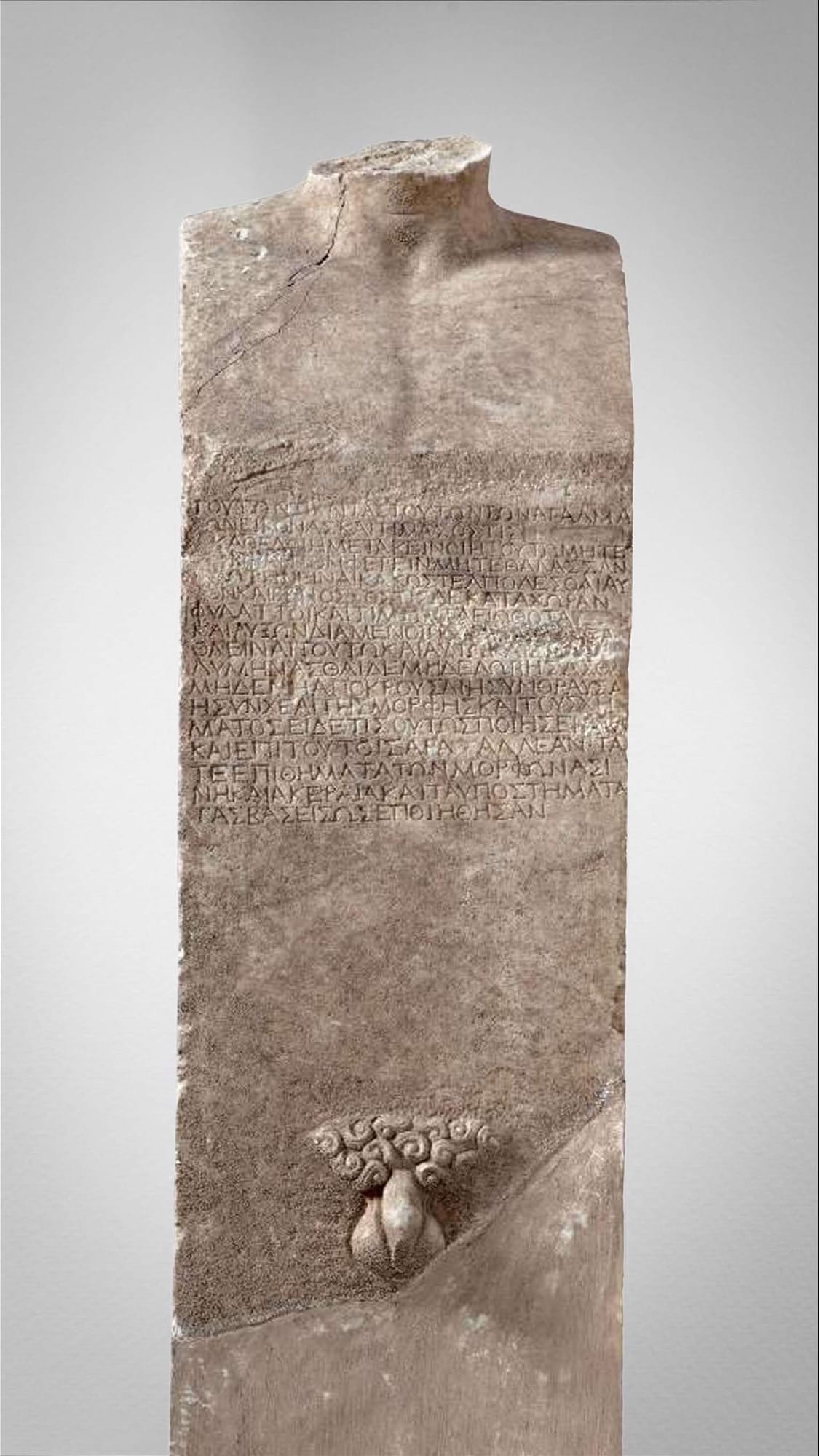

Herodes also commissioned a poem, inscribed on two marble stelai (a stone or wooden slab from the Greek word στήλη) along the Appian Way, further transforming the Triopion. This poem blended elements of hymn, epitaph, and funerary imprecation, reimagining the estate as a commemorative space that honored Regilla and memorialized their bicultural relationship.

“Come, daughters of Tibur, to this shrine, ladies who bring incense offerings to the abode of Regilla; she was born of the wealthy race of Aeneas, the famed stock of Anchises and Idean Aphrodite; she married into Marathon.

The heavenly goddesses Old and New Demeter honor her, goddesses in whose shrine the image of the lovely-girded woman Is dedicated.”

Credits: Kleuske, CC BY-SA 3.0, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Public domain

The opening lines of the poem invite the "daughters of Tibur" to approach Regilla’s temple-shrine with offerings of incense, using the phrase ∆εῦρ’ ἴτε Ѳυβριάδες νηόν ποτί τόνδε γυναῖκες ("Come here, daughters of Tibur, to this temple, women").

This group, presumably Roman women, may have been represented by a nearby bas-relief showing three women in laurel wreaths and mural crowns, gracefully carrying offerings. The poem’s hymnic style recalls Callimachus' Hymn to Demeter, which begins similarly, calling women to a ritual and ends with the cautionary tale of Triopas, who was punished for desecrating a Demeter sanctuary.

In this poem, Regilla’s ancestry is presented with an unusual mix of myth and local connection. She is initially linked to the mythic lineage of Aeneas, Anchises, and Aphrodite, grounding her origins in legendary Troy. However, the poem then quickly shifts her identity to Greece, specifically to the Attic deme of Marathon, entirely bypassing the Roman ancestry and consular heritage that connected her to the Empress Faustina.

This subtle merging of Greek and Roman elements continues, as Faustina is referred to as "New Demeter" and only appears much later in the poem, her role seemingly secondary to honoring Regilla’s Hellenic identity in the shrine. (Making Space for Bicultural Identity: Herodes Atticus Commemorates Regilla Maud W. Gleason, Stanford University)

Regilla as an Inspiration for Herodes

Regilla is described with the Homeric epithet εὐζώνοιο γυναικός ("lovely-girded woman"), a phrase that appears only in The Iliad when Achilles mourns the loss of Briseis. By bestowing Briseis’s epithet on Regilla, the poem implicitly casts Herodes as Achilles, grieving deeply for her, a likeness that becomes explicit when Herodes is described in a posture of sorrow just a few lines later.

Herodes Atticus and his wife, Regilla, have been celebrated as significant benefactors in Greece, especially in Athens, from the 2nd century onward.

Odeon of Herodes Atticus, built in 161 AD on the south slope of the Acropolis of Athens in memory of his wife Annia Regilla, Athens, Greece. Credits: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0

Their legacy is honored through Herodou Attikou Street, Rigillis Street and Rigillis Square in central Athens. In Rome, their influence is similarly recognized, with streets named after them in the Quarto Miglio suburb, near the site of the Triopion estate. Herodes Atticus was renowned for his literary contributions—most of which are now lost—and for his extensive philanthropy and public works. He financed more construction projects in Roman Greece than anyone besides the emperors. His contributions included:

- The Panathenaic Stadium in Athens, which he rebuilt using only marble

- The Odeon in Athens, a marvel of ancient acoustics, dedicated to the memory of his wife

- A theater in Corinth

- A stadium in Delphi

- The baths at Thermopylae

- An aqueduct at Canusium in Italy

- An aqueduct at Alexandria Troas

- A nymphaeum (fountain) at Olympia with his wife Regilla

- Various charitable projects for the people of Thessaly, Epirus, Euboea, Boeotia, and the Peloponnese

- He also considered digging a canal through the Isthmus of Corinth but was dissuaded by previous unsuccessful attempts, including that of Emperor Nero.

Herodes had a turbulent relationship with the citizens of Athens, though they reconciled before his death. Upon his passing, the Athenians honored him with a distinguished burial, holding his funeral at the Panathenaic Stadium, (which was later reconstructed for the 1896 Olympic Games and remains a significant monument in the city), a monument he himself had commissioned to become the world’s only stadium built entirely by marble, which remained in history as The Kallimarmaron, meaning the beautiful marble.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: