Hadrian’s Wall: The Roman Empire’s Enigmatic Frontier

Hadrian’s Wall is one of the most significant and well-preserved remnants of Roman Britain.

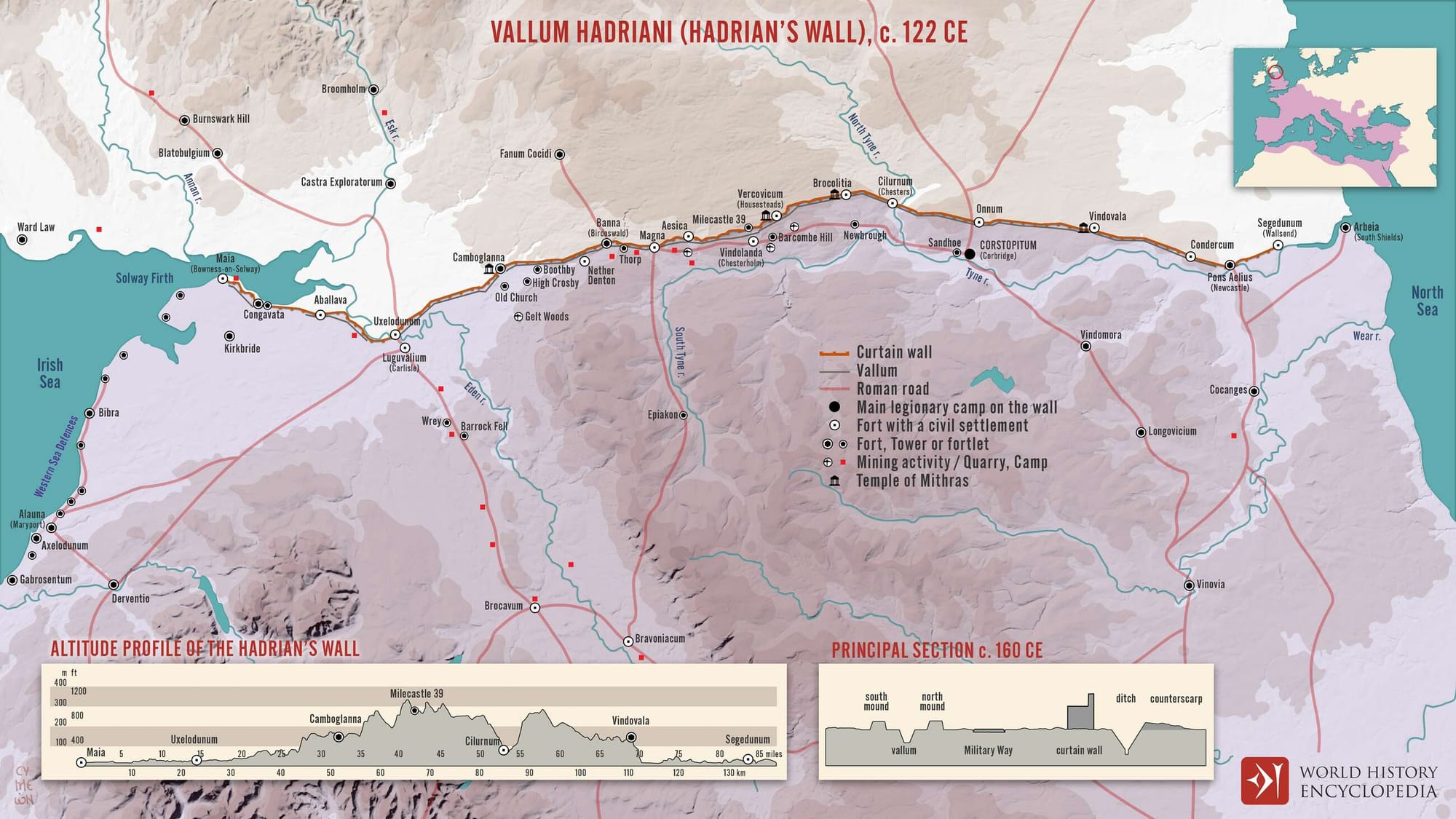

Hadrian’s wall was constructed under the orders of Emperor Hadrian, who ruled from 117 to 138 CE. The wall marked the northern boundary of the Roman Empire in Britain, stretching across the width of the island from the River Tyne near the modern city of Newcastle in the east to the Solway Firth on the west coast.

David J Breeze and Brian Dobson, in their book, “Hadrian’s Wall” start their narrative saying that the only surviving Roman explanation for Hadrian’s decision to build the Wall comes from the Scriptores Historiae Augustae, which states that Hadrian was the first to construct a wall, eighty miles long, to separate the Romans from the barbarians.

This raises the question of why, nearly eighty years after the Roman invasion of Britain under Emperor Claudius in A.D. 43, Hadrian, as the tenth emperor, decided in A.D. 122 to establish artificial boundaries where natural ones did not exist. Moreover, why did he choose to create a wall in Britain to effectively separate the Empire’s inhabitants, from the barbarians outside?

To grasp the reasoning behind this decision, one must examine the history of the province within the broader context of the Roman Empire.

Romans and Barbarians

By A.D. 43, Rome had a rich history spanning over eight centuries, with its origins traditionally traced back to the mid-eighth century B.C., though evidence suggests settlements as early as the tenth century B.C.

Since the city’s sacking by the Gauls in 390 B.C., Rome had rarely experienced defeat, notably triumphing in the Second Punic War against Hannibal at Zama in 202 B.C. This victory marked the beginning of Rome’s dominance, with no power able to challenge its unmatched military, particularly in open-field battles.

Rome was thus compelled to take on the role of a supreme power, even when it was reluctant to do so.

A representation of a Roman sword, pinned on the British countryside ground. Illustration: Midjourney

The concept of establishing a permanent boundary between Romans and barbarians was unthinkable, as it would limit Rome’s potential for further conquests. Rome’s strength was seen in its ability to govern and wage war, a sentiment echoed by Vergil, who highlighted the Roman duty to impose peace through force, offering mercy to those who submitted and crushing the defiant.

During Augustus’ reign, the idea of world conquest seemed within reach. The known world was believed to span about 10,000 miles east-west and 4,000 miles north-south, and Augustus claimed to have nearly completed its conquest in his Res Gestae divi Augusti.

Roman military strategy focused on mobilizing legions for quick, decisive battles, aiming to defeat enemies so thoroughly that they would seek peace. Forts were primarily used as winter quarters or to manage newly conquered tribes, with few being garrisoned during campaigns. Rivers like the Rhine and Danube were more like convenient stopping points rather than permanent borders, serving as routes for movement and trade rather than strict cultural divides.

From Augustus’ reign starting in 31 B.C. to the late 80s A.D., Rome’s expansion strategy was cautious. Under the Republic, generals expanded Rome’s territory for personal glory, but under the Empire, emperors had to carefully manage expansion, limiting their governors’ power to maintain control. Only the most secure emperors would risk advancing on multiple fronts.

Augustus’s shock at the loss of three legions in Germany in A.D. 9 led him to advise his successor, Tiberius, to maintain the Empire’s current boundaries. Tiberius, already tired and disillusioned, followed this advice, resulting in nearly thirty years of halted expansion.

Hadrian’s Wall: The Beginning

Hadrian’s Wall is a concept that reflects Hadrian’s vision and embodies his character and policies. Like Trajan, Hadrian followed the typical career path of a Roman senator, serving with distinction as a legionary tribune, commander, and provincial governor. Despite faithfully serving Trajan and likely being groomed as his successor, Hadrian’s approach was fundamentally different from Trajan’s.

Upon becoming emperor, Hadrian aimed to establish permanent borders for the Empire, starting by relinquishing Trajan’s unsustainable conquests in the East. He then embarked on two extensive journeys to inspect all the Empire’s armies, ensuring they were well-trained and disciplined, while also gaining their loyalty by addressing their welfare and eliminating abuses.

Hadrian’s policy was clear: maintain peace, secure stable and controlled frontiers, and keep a well-disciplined army, all under the watchful eye of a travelling emperor.

When Hadrian assumed power in 117, he encountered unrest in Britain. His biographer notes simply that ‘the Britons could not be kept under Roman control.’ A coin from 119 bearing the inscription BRITANNIA is generally interpreted as signalling a victory in Britain, which could imply either internal unrest or external attacks.

Cornelius Fronto, writing to Emperor Marcus Aurelius in 162, mentions a significant loss of soldiers during Hadrian’s reign due to conflicts with both Jews and Britons. The Jewish war occurred in the 130s, but the British conflict could have happened at any time during his rule. These losses were likely serious and may have been linked to the disturbances early in Hadrian’s reign.

However, it is clear that the Ninth Legion, which spawned legendary tales, was not destroyed in Britain at this time, as was once believed. The legion was still active in the 130s, and recent theories suggest it may have been transferred from Britain to Lower Germany by Trajan or Hadrian, and then moved to the Eastern provinces, possibly meeting its end in Armenia at the hands of the Parthians in 161.

In response to the early unrest in his reign, Hadrian decided to address the situation on Britain’s northern frontier.

A part of Hadrian's stone wall, in Britain. Credits: Martyn Wright, CC BY 2.0

Rather than expanding further, Hadrian, who favored consolidation over expansion, chose to enhance the existing frontier along the Tyne-Solway line instead of attempting to conquer the entire island or advancing to the shorter Forth-Clyde isthmus.

Hadrian personally visited Britain in 122 and took a direct interest in resolving the frontier issue. Unlike other frontiers of the Empire, which were typically defined by natural barriers like seas, rivers such as the Rhine or Danube, or deserts as in North Africa, Northern Britain lacked a clear natural boundary. Therefore, Hadrian decided to establish a definitive frontier by constructing a wall from coast to coast, effectively creating a division between the Romans and the barbarians, as noted by his biographer.

Frontiers have often been viewed as transitional zones of contact between the Roman state and various ‘barbarian’ groups, making it valuable to examine a relatively universal social group present in every frontier: the limitanei. Several factors make the limitanei an ideal group for study.

First, they were stationed across all frontiers of the later Roman Empire, allowing for comparative analysis between different frontiers. As professional soldiers, they were deeply integrated into the Empire’s politico-military framework, both economically, socially, and ideologically.

Additionally, the long-term stability of Roman frontiers, the tendency to recruit locally, and the preference for tax in kind during the later period further embedded the limitanei within the frontier communities where they were stationed. Through the study of the limitanei, one can connect the frontier regions to the broader imperial system while also understanding them in their localized context.

Research on the Roman army has shifted focus towards social aspects, challenging unwarranted comparisons with modern armies and highlighting the relationships between soldiers and their local communities beyond their role as paid fighters.

While relationships between garrisons and non-military populations likely varied across the Empire, there may be a sociological and anthropological understanding of ‘community,’ most evident in the concept of an occupational community. (Late Roman frontier communities in northern Britain: A theoretical context for the ‘end’ of Hadrian’s Wall, by Rob Collins)

The Roman Wall

The Roman ‘Wall’ is an impressive and extensive ancient monument. Scholars currently believe it was constructed in the AD 120s as part of a broad zone centered around a substantial stone curtain wall, measuring 80 miles in length and approximately 3.5 meters in height. This stone wall was accompanied by a large ditch to its north and was intersected by small fortified gates, or ‘milecastles,’ every mile, with two smaller turrets placed between each milecastle.

Just south of the wall lies a mysterious earthwork known as the Vallum. Additionally, sixteen Roman forts, each associated with sizable civilian settlements called vici, were closely connected to the Wall. Numerous Latin inscriptions, temples, and religious dedications have been found among the Wall’s ruins, with new discoveries continuing to emerge.

Archaeologists believe that the Wall likely ceased to function as a Roman frontier in the early fifth century. Although some communities continued to inhabit the settlements along the Wall into the late fifth century and beyond, the Wall itself seems to have fallen into disuse and abandonment after the fifth century.

While it is often referred to as ‘Hadrian’s Wall,’ this Roman identity may not be the only aspect that should interest archaeologists and the public. Even after its Roman abandonment, the Wall’s physical remains persisted in the landscape, continuing to hold significant cultural and political importance.

The construction of Hadrian’s Wall seems to indicate that the previous frontier arrangements were inadequate. A continuous barrier, such as a wall, was deemed the only truly effective way to control small-scale movements, prevent minor raids, deter large-scale invasions, and promote peaceful development up to the frontier.

The Wall was designed with the critical east-west communication route, the Stanegate, in mind, running through the Tyne-Solway gap. Its placement on the north side of this isthmus, staying north of the rivers in the gap until Carlisle, emphasized its strategic intent. The Wall was intended to stretch 76 Roman miles (about 70 modern miles or 113 km) from Newcastle upon Tyne, where a new bridge named Pons Aelius was built in honor of the emperor, to Bowness-on-Solway.

This extended the Wall further east and west than the defined Stanegate road. The eastern 45 Roman miles from Newcastle to the river Irthing were planned as a stone wall, 10 Roman feet wide, while the western 31 Roman miles from the Irthing to the Solway were to be a turf wall, 20 Roman feet wide at the base.

In its central portion, the Wall utilized the Whin Sill, a volcanic outcrop that forms a line of north-facing cliffs, which is the most well-known and photographed section, located between the rivers North Tyne and Irthing. To the east and west of the cliffs, the Wall traverses varying terrain. In the east, it extends from the cliffs to Limestone Corner, the Wall’s northernmost point, before heading towards the bridge at Newcastle, with only minor deviations as it follows the natural elevations.

The Wall crosses the North Tyne at Chollerford, near Chesters, where the North and South Tyne rivers converge just above Hexham. West of the cliffs, the Wall moves towards the river Irthing, crossing it at Willowford and then running along the north side of the Irthing gorge, facing the Spadeadam wasteland. The landscape softens after the transition from limestone to sandstone at the Red Rock Fault, but a more dramatic change occurs after crossing the Eden at Stanwix, where the Wall reaches the marshes of the Solway at Burgh-by-Sands, continuing just above the high-water mark until it reaches the sea near Bowness.

For much of its length, the Wall offers a decent view to the north, with some areas providing an impressively wide vista. However, in certain places, such as from Great Chesters westward, the view is restricted. Despite this, the Wall follows the most direct and convenient route, even if this left some areas of dead ground to the north. This was acceptable because the Wall was not intended to be defended in the same manner as a city, or fort wall.

Constructing the Roman Wall

Hadrian’s Wall was constructed with a ditch in front of it, except in areas where the terrain made it unnecessary, such as on the Whin Sill, or where digging through solid rock, like at Limestone Corner, was impractical.

This ditch was separated from the wall by a flat space, or berm, which was 20 feet wide on the stone wall and 6 feet wide on the turf wall. The ditch typically measured between 26 to 40 feet in width, with a depth of 9 to 10 feet, and had a V-shaped profile with a square-cut drainage channel at the bottom. The excavated material from the ditch was piled on the north side to increase the height of the outer edge.

In some locations, such as Limestone Corner, the ditch was not fully completed, with large stones left in place. The wall itself was built using locally quarried sandstone, with roughly dressed stones on the outer faces and a core of rubble, usually bonded with mortar. Drains were incorporated into the foundation where water was likely to collect, and streams were culverted through the wall. Major river crossings, such as the North Tyne at Chesters and the Irthing by Willowford, featured stone piers supporting bridges.

The exact height of the wall is uncertain, but estimates suggest it may have been around 14 feet (±4.2 meters) high.

The North Gate Arch on Milecastle 37 of Hadrian's Wall. Credits: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA-4.0

Evidence from milecastles indicates heights ranging from 12 to 14 feet, with some suggesting the wall could have been as high as 15 to 16 feet to allow soldiers to see into the ditch. However, if the wall was not patrolled, this height might not have been necessary. The wall may have been lowered when it was narrowed later in its history, but there is no conclusive evidence of this.

Why turf?

The turf wall was constructed using standardized turves, each cut to a military regulation size of 18 by 12 by 6 Roman inches. When a section of the turf wall is exposed, the dark lines from the grass in the turves are still visible. What remains of the wall suggests that the front had a steep slope, while the back started vertical before continuing at a gentler angle.

The reason why part of Hadrian’s Wall was built in turf rather than entirely in stone remains unclear. The later reconstruction of the turf sections in stone indicates that it was possible to build the entire wall in stone from the start. This raises the question of why the stone sections of the wall were built to such a substantial width of 10 feet (3 meters), when later parts were only 6 feet (1.8 meters) wide. Some have speculated that the massive construction might have been influenced by accounts of the Great Wall of China, though this seems unlikely as the Great Wall’s current form is due to much later work.

It’s possible that the grand scale of the stone wall was intended as a lasting monument to Emperor Hadrian, who did not pursue military conquests. However, if that were the case, the decision to construct part of the Wall in turf is puzzling.

One theory suggests that west of the Red Rock Fault, where limestone for mortar was scarce, building in stone might have taken longer, making the turf wall a temporary solution, but more evidence is needed to confirm this. It is also unlikely that the turf wall was built in haste to counter a northern threat, as any such threat would have been managed by the Roman army independently of the Wall.

The presence of three outpost forts just north of the Wall’s western end has been interpreted as indicating a threat from southwest Scotland, but it might be more accurate to view these forts as protection for a region of the province, possibly Brigantian tribal territory, that was isolated by the construction of the Wall.

A wall of memories

A very interesting aspect of Hadrian’s wall is presented by Richard Hingley in his article: Living Landscape: Reading Hadrian's Wall.

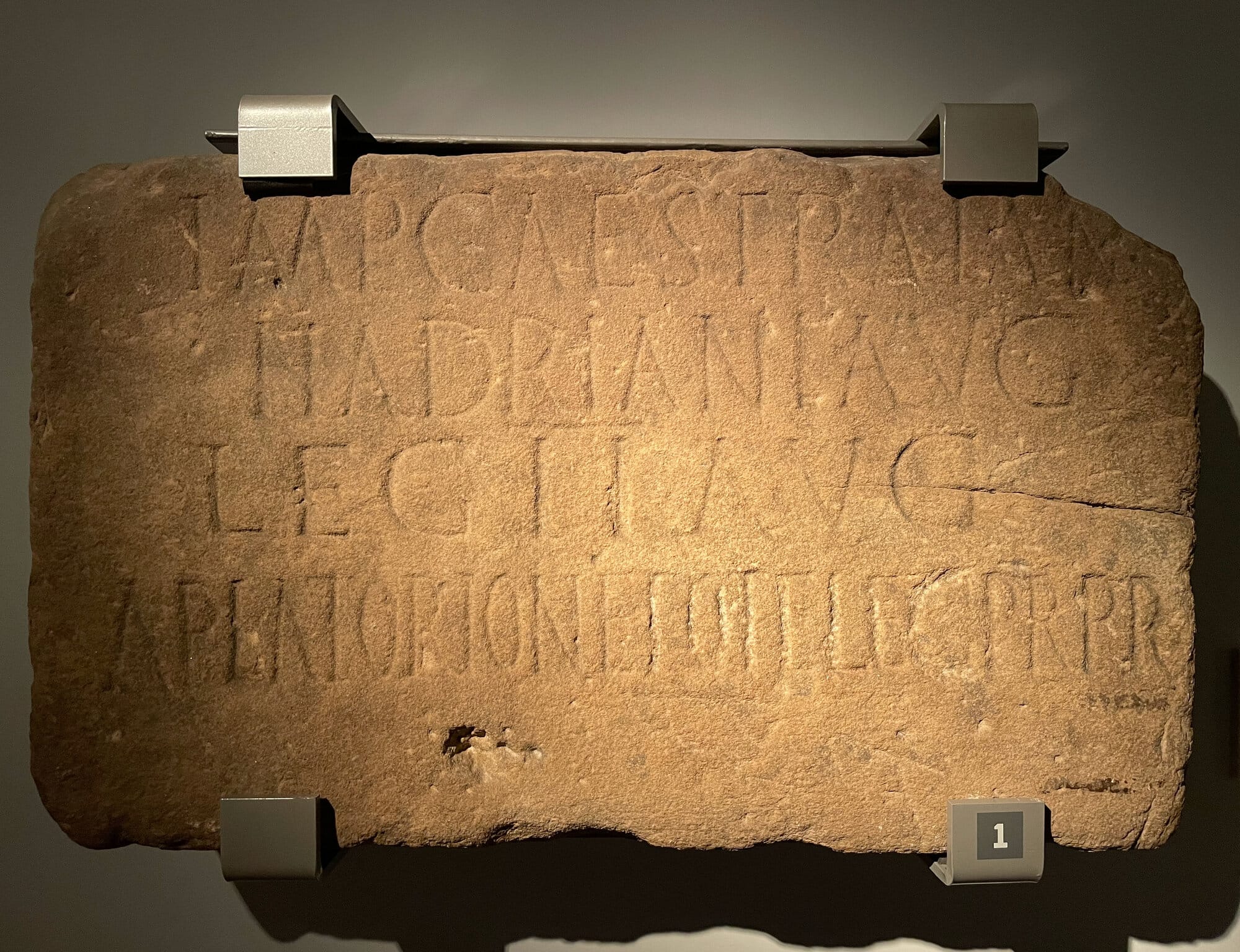

Hingley suggests that one aspect of Hadrian’s Wall that has not been adequately explored is the religious beliefs of its inhabitants. Since the late sixteenth century, numerous Roman inscribed stones have been discovered along the Wall by antiquaries, landowners, and archaeologists. Some of these discoveries contributed to local folklore, such as tales of giants.

Many of the stones are inscribed with the names and images of gods and goddesses worshiped during Roman times. To protect these stones from environmental damage and vandalism, they have often been removed from their original locations and placed in nearby museums, such as those at Chesters, Corbridge, Vindolanda, Housesteads, Carlisle, and Maryport.

However, this practice has effectively stripped the Wall of its religious significance and removed a humanizing element, as the stones also named and sometimes depicted people who lived along the Wall, including women, children, and non-military men, as well as soldiers.

In the twentieth century, academic focus shifted to viewing the Wall as a ‘rational’ military structure, leading to the removal of ritual remains from the forts and settlements along the Wall. However, the Wall is not just a Roman military structure; it is the product of generations of people who have physically and conceptually shaped it.

Credits: Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin, Carole Raddato, CC BY-NC-SA-4.0

Each generation has contributed to remaking the Wall in both physical and metaphorical terms, meaning there is no singular, authentic version of the Wall. If this ongoing process of reinterpretation and reimagining were to stop, the Wall would cease to exist in a meaningful way.

Despite this, the core of the landscape remains the Roman structures built between the second and fifth centuries. Although some are deeply buried, these remains are still important, and efforts continue to protect, preserve, and study them. The archaeological imagination should aim to bridge the gap between the past, seen as distant and unapproachable, and the present, where we interpret and understand this evidence.

The “silent immediacy” of the past should inspire new interpretations and approaches. However, there is a concern that the popular portrayal of the Wall as an inclusive landscape might downplay its original role as a divisive frontier imposed on a potentially resistant, indigenous population.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: