From Lemuria to Halloween: Rome’s Ancient Festival of Spirits

Long before Halloween, Romans held Lemuria—a midnight festival to appease ghosts with beans and bronze, guarding their homes from restless spirits.

Long before jack-o’-lanterns flickered in the dark, Romans spent May nights casting beans to banish ghosts. The Lemuria was their most haunted festival—a ritual born of fear and reverence, when the living sought to pacify the restless dead.

Each household turned into a small sanctuary of protection as heads of families rose at midnight, barefoot and silent, to offer black beans to wandering spirits. Through these gestures, the Romans kept their uneasy peace with the invisible world—an ancient ancestor of what we now call Halloween.

The Month of Shadows: May and the Lemuria

In Rome’s sacred year, May carried a reputation of unease. Its very name, Maius, was uncertain in origin — some said it came from the goddess Maia, others from the word maior, meaning “greater” or “growing.” The ambiguity reflected the month’s dual nature: a time of renewal, but also of purification and taboo.

It was a period when marriages were avoided, when the air itself was thought to thicken with unseen forces, and when the living took precautions against the dead. The rituals of May reveal a city walking carefully between fertility and fear.

The calendar began with the Kalends of May, sacred to Maia and the Bona Dea, the “Good Goddess,” whose mysterious cult was confined to women. Her Aventine temple barred men from entry and even banned words such as vinum (wine) within its walls — the drink could only be referred to euphemistically as “milk.”

Myrtle was also forbidden, and the rites, conducted by priestesses, blended fertility, healing, and secrecy. In ancient explanations, the goddess was said to embody the Earth itself, addressed under many names — Fauna, Ops, and Terra among them.

Her temple stored herbs with curative powers, and snakes, symbols of both renewal and medicine, coiled freely within its precincts. A porca (sow) was her customary sacrifice, linking her to other earth deities such as Ceres and Juno Lucina. The Bona Dea was not a household goddess but a vestige of Italy’s rural past — a maternal spirit whose fertility and protection extended to all living things, yet whose cult remained veiled in ritual silence.

The early half of May was punctuated by other rites of cleansing and transition. The Argei, performed around the Ides, involved the ritual drowning of straw effigies in the Tiber — an expulsion of impurity on a civic scale. Toward month’s end, the lustratio of the crops purified the fields before harvest, while the Vestal Virgins labored from the 7th to the 14th to prepare the mola salsa, the sacred salted meal used in Rome’s sacrifices.

Each act reaffirmed purity and fertility at a time of anxiety about growth and decay. But it was the Lemuria, held on the 9th, 11th, and 13th of May, that most fully revealed the month’s dark heart.

The Lemuria: Rome’s Night of the Restless Dead

The Lemuria was one of Rome’s strangest observances — neither wholly public nor private, ancient even in Ovid’s time. It was devoted to appeasing the lemures, wandering and hostile spirits distinct from the honored manes, the peaceful ancestral dead.

While the Feralia in February honored family ancestors within the civic order, the Lemuria dealt with what lay outside it: the unburied, the forgotten, the violently dead. These spirits were not welcomed but banished, lest they bring sickness or misfortune to the household.

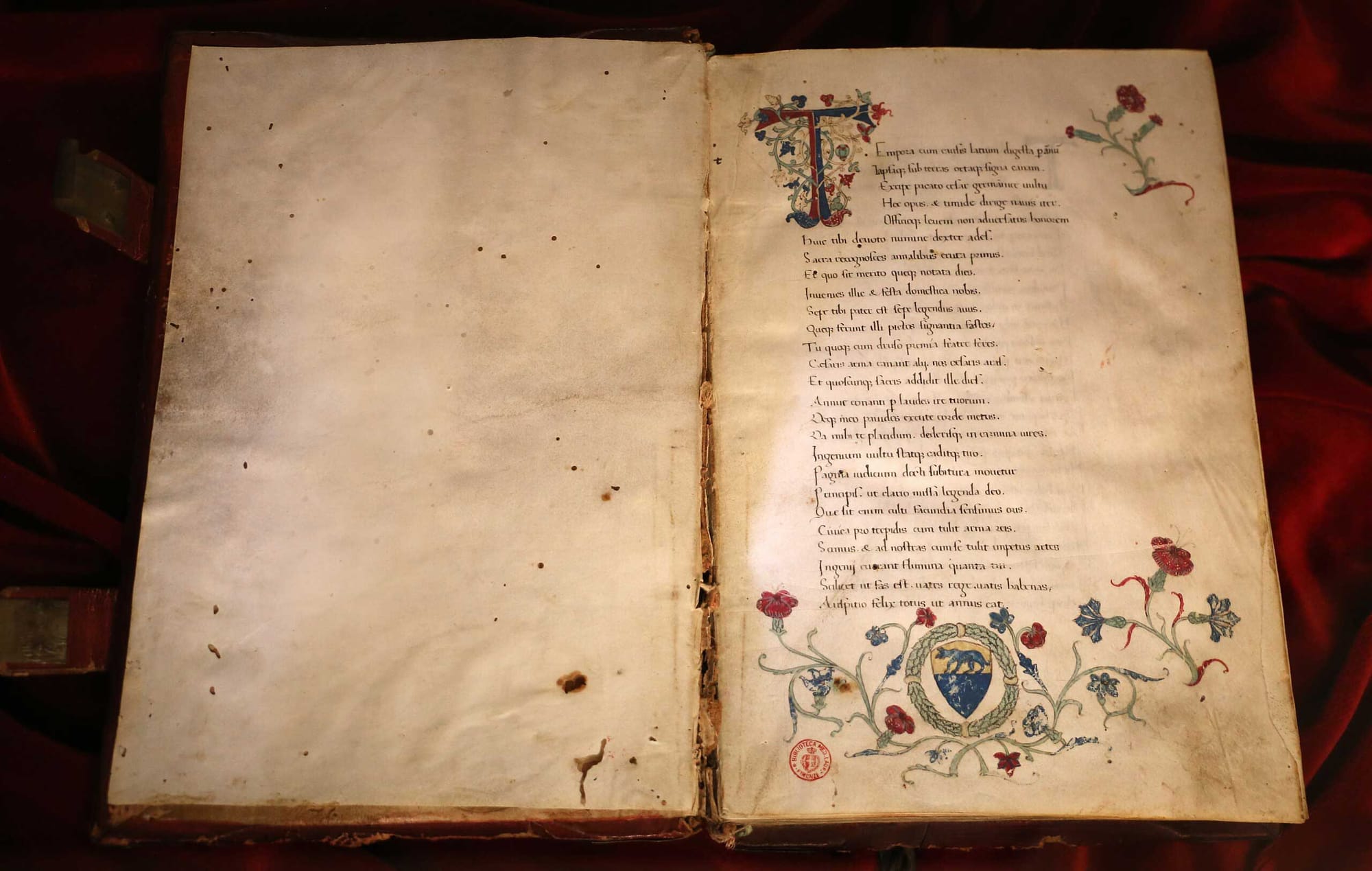

Ovid in his Fasti (Book 5, 419–492) is the only ancient witness to describe the rite in detail, and even he writes with fascination and unease.

The number nine, sacred and ominous, was common in rites of expiation; its repetition reinforced the act’s solemnity and completeness. The black beans, meanwhile, carried a mystery as old as Italy itself. Both fertility symbol and funerary offering, they served as ransom — gifts to feed or distract the dead, allowing them to pass without harm.

Ancient writers disagreed on their meaning: some believed the beans absorbed souls; others thought the spirits consumed them to gain a temporary renewal of life. Whatever their origin, the Romans treated beans with ambivalence: the high priest of Jupiter was forbidden even to touch them, a vestige of the same fear that filled the Lemuria nights.

These ceremonies, though performed at home, were marked in the public fasti — the official calendars — with large letters, suggesting that Lemuria had once been a state festival. In its earliest form, the Lemuria may have been part of a broader civic rite to purge the community of harmful spirits. Over time, as Rome’s religious life became more structured and urban, that collective exorcism retreated into the private sphere.

What had once been performed for the safety of the city was now enacted by each household for its own protection. The paterfamilias, guardian of the domestic order, reenacted on a smaller scale the purification once carried out for all of Rome—his home a miniature city, guarded by its Lares and shielded from the restless shades that lingered beyond its threshold.

The Nature of the Lemures

The Romans distinguished sharply between classes of the dead. The manes were the benevolent ancestors, integrated into family and state cult; the lemures and larvae, by contrast, were feared as restless, vengeful, or unburied. Later authors blurred these categories, but in the Roman imagination they represented different moral and emotional relationships with the departed.

The lemures lingered uneasily between worlds — not honored enough to be worshipped, yet not powerless enough to ignore. Their festival, therefore, was marked as nefastus, a day unsuitable for public business, contrasting with the feriae of the Feralia, which celebrated ancestral continuity rather than appeasing spiritual danger.

Ovid himself traced the festival’s origin to Remus, whose violent death and unburied body, he claimed, were first appeased through these rites. From his name, he said, came Remuria, later Lemuria. Whether true or not, the story captured the Roman belief that unquiet spirits arose from unburied wrongs — and that ritual, properly performed, could heal even that breach between the living and the dead.

Echoes of a Forgotten World

The Lemuria was not a night of mourning but of ritual control. Romans did not weep for the ghosts; they commanded them. The rites reveal a people for whom religion was an instrument of order — a negotiation not only with gods but with the darker forces beneath them. Through beans, bronze, and formula, they reenacted the eternal task of Roman piety: restoring balance between the visible and invisible worlds.

By the time of Ovid, the festival’s public meaning had faded, but its gestures endured in households across the empire. Each May, Roman families repeated words older than their language, walking through their homes as the patriarchs of old had walked through the early city—silencing the dead, protecting the living, and reaffirming that even the restless shades of the past could be pacified by ritual.

In this sense, Lemuria was Rome’s own night of spirits, the ancestor of later customs that turned fear into ceremony — a reminder that every civilization, in its own way, must learn to live with its ghosts. (The Roman festivals of the period of the Republic, by W. Warde Fowler)

By the turn of the first century CE, the Lemuria lived on not in public squares but in poetry. Ovid, ever the antiquarian storyteller, immortalized it in his calendar poem, the Fasti.

Ovid and the Night of the Restless Dead

Ovid’s Fasti preserves the only detailed account of how Romans once honored the spirits during Lemuria. In his telling, the ancient domestic rite becomes both ritual and poetry—a moment where household piety and ghostly fear intertwine. The poet describes the ceremony unfolding in the stillness of night:

“When midnight comes, and silent sleep holds every creature, the head of the household rises and, barefoot, makes the sign to ward off ghosts.”

Purified by water, the paterfamilias walks through his home, carrying the weight of tradition in each gesture. He takes black beans into his mouth and spits them behind him one by one, reciting the formula:

“With these I redeem me and mine.”

He repeats the words nine times without looking back, while unseen spirits gather the beans as tokens of appeasement. Once the offering is complete, the ritual turns to expulsion. The man washes again, strikes bronze to break the silence, and cries out nine times:

“Depart, ancestral shades!”

With the echoes fading, the living reclaim their space. The house is cleansed, the barrier between worlds restored. What began as superstition ends as order—a miniature drama of Rome itself, where fear of the unseen yields to the discipline of ritual.

In Ovid’s vision, this private ceremony mirrors the public rhythm of Roman religion: an act of duty performed not out of devotion but necessity. He roots the rite in myth, tracing it back to Remus—murdered by his brother and returning as a restless shade to demand remembrance:

“The shade of Remus came, asking that honor be given to the dead. Hence the month’s rites to the spirits—the Lemuria.”

Thus, May—the month once marked by rites for the dead—remained forever shadowed in memory. As Ovid notes,

“The month of May was once ill-famed for weddings—its days were shadowed by the rites of the restless dead.”

Through Ovid’s art, the Lemuria becomes more than folklore. It stands as a meditation on loss, remembrance, and the fragile peace between living and dead. Each whispered invocation and each bean cast into the darkness carries the weight of Rome’s oldest fear—the fear that the dead, if forgotten, might return. (Ovid among the Family Dead: the Roman Founder Legend and Augustan Iconography in Ovid's' 'Feralia' and 'Lemuria', by R. J. Littlewood)

Long after Ovid’s verses faded from living memory, the shadows of Lemuria lingered in Roman imagination. The festival’s spirit—its midnight silence, its fear of the unappeased dead, its careful rituals of purification—carried forward the Roman conviction that the boundary between worlds could never be fully closed. The beans, the bronze, the whispered invocations of “manes exite paterni” were not remnants of primitive superstition but expressions of a civilization profoundly aware of continuity between past and present, the living and the lost.

In time, as Christianity reshaped Rome’s spiritual landscape, the ghosts of Lemuria found new guises. The Church redefined the days of the dead into commemorations of saints and souls, yet beneath these transformations the old pattern remained: remembrance, cleansing, protection. Festivals such as All Saints’ and All Souls’ absorbed the older rhythm of appeasement and renewal once embodied by Lemuria.

Even modern Halloween, stripped of its theology and reborn as folklore, echoes that same Roman inheritance—the night when the living acknowledge the unseen, when fear becomes ritual and memory becomes devotion. Through centuries of change, the essence of Lemuria endures: a quiet rite of reconciliation between order and chaos, light and shadow, life and the ghostly persistence of those who came before.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: