Flavors Rome Never Forgot

Across kitchens, workshops, and banquet halls, traces of a forgotten craft linger in scattered texts and quiet archaeological clues. What survives hints at small pleasures once woven into daily life, shaped by custom, technique, and the rhythms of the ancient table.

Somewhere between the steam of the kitchen hearth and the glitter of banquet halls, the Romans created small pleasures that rarely make it into history books. They were not grand monuments or imperial decrees, but fleeting comforts—crafted, shared, and remembered in quieter moments. A handful of ingredients, a little fire, and a great deal of imagination were enough to leave echoes of sweetness that have survived in recipes, inscriptions, and the charred remains of ordinary homes. What follows is the story of how Rome satisfied its cravings.

Quince Pastes in the Ancient Mediterranean

Quince preserves were among the earliest sweets to close a meal in antiquity, and long before medieval confectioners refined them with sugar, both the Greeks and the Romans were already preparing concentrated quince pastes sweetened with honey. These pastes were often enriched with warming spices—cinnamon, ginger, or even wine—to create a dense, aromatic sweet that could be sliced, stored, and served alongside fruit or cheese at the end of a meal.

In Rome, quince paste functioned not as a frivolous treat but as a kind of semi-luxury food with medicinal undertones, prized for its digestive qualities. Through the centuries this tradition endured: later medieval Arab confectioners replaced honey with sugar, and Iberian cooks carried the recipe forward as membrillo (Spain) and marmelada (Portugal), but its origins lay squarely in the kitchens of Greece and Rome.

Early Roman “Cheesecake”: Honeyed Cheese Discs, Not Modern Dessert Cakes

The cheesecakes known to Greeks and Romans bear almost no resemblance to the creamy, tall desserts familiar today. Instead, ancient versions were compact discs made from fresh cheese blended with honey. Their dense, rustic texture reflected the ingredients available at the time—simple dairy, honey, and occasionally flour—rather than the rich, egg-laden recipes that emerged in later centuries.

Though plain by modern standards, these early cheesecakes held an important place in Roman food culture. They were served during religious observances, used as offerings, or featured as simple sweet dishes after meals. Their longevity illustrates how deeply dairy-based sweets were embedded in Mediterranean culinary traditions long before sugar, spices, or complex baking techniques reshaped dessert as we know it.

A Roman Name That Endured: Mostaccioli Romani

Mostaccioli appears as a sweet whose very name carries a Roman lineage, described among its traditional variants as mostacciole or mostaccioli romani. Its naming preserves an ancient association with Rome, showing how certain confections retained a link to the city through their identity and vocabulary.

To understand the deeper origin behind this name, ancient sources point to an earlier cake known as mustacei. These were prepared with grape must, combined with flour, anise, and soft cheese, then baked on bay leaves for fragrance. Mustacei appeared especially at weddings and festive rural gatherings, forming part of a longstanding tradition of sweet, aromatic cakes tied to celebration and season. (Cato, De Agri Cultura 121)

Fruit as the Roman Finale: The Earliest “Dessert” Course

In the ancient world, including Rome, meals ended not with elaborate pastries but with fruit. Fresh, dried, or cooked fruits were considered appropriate closers for a meal according to long-held dietary beliefs. Dried dates, raisins, figs, melons, cherries, grapes, and pears all appear in ancient sources as suitable concluding foods.

Humoral theory—which the Romans inherited from Greek medicine—classified raw fruits as “cold” and therefore potentially harmful unless balanced with something warming. Cooked fruit solved this problem, and wine served alongside fruit was believed to counteract undesirable effects. Warm spices such as cinnamon, ginger, and anise reinforced this digestive purpose.

As a result, a Roman “dessert” was not a sugar-heavy course, but a practical and health-oriented combination of fruits and occasionally cheese—an approach that shaped post-meal eating habits across Europe for centuries

Nuts, Wine, and Sweet Spices: A Shared Mediterranean Tradition

The Roman preference for dried fruits, nuts, and spiced wines at the end of meals fits a larger Mediterranean pattern. Foods believed to “close” the stomach—aged cheeses, dried figs, raisins, walnuts, and warmed wine—were brought together to help complete digestion.

Even though many medieval doctors later debated the dangers of raw fruits, their recommended remedies—cooking fruit in wine, adding warming spices, pairing nuts with pears—echo practices that were already familiar in Roman dining. While not all these medieval texts explicitly name Roman precedent, the parallels are clear: Rome’s final course was simple, fruit-forward, and medicinally aligned. ("Dessert, A Tale of Happy Endings" by Jery Quinzio)

Rome Before Sugar: A World Sweetened by Honey

Long before cane sugar entered Mediterranean kitchens, Rome relied on a very different palette of sweetness. Honey stood at the center of that world, shaping every level of Roman confectionery. It flavored the small cakes served at banquets, enriched thickened milk and soft cheeses, and bound together mixtures of nuts and grains. For Romans, honey was not an occasional embellishment but the foundation of all sweet dishes.

It entered the culinary tradition so early and became so deeply embedded that it held its place unquestioned for centuries, joining other staples of the Roman table as one of the pillars of indulgence.

Across the broader Mediterranean, honey was collected in the wild long before systematic beekeeping appeared, and techniques for managing hives had been refined well before Rome rose to prominence. Roman cooks drew upon these older practices, using honey with an ease that suggests long familiarity. In feasts and private gatherings alike, honeyed cakes made regular appearances, affirming both abundance and hospitality. Whatever its form, sweetness in Rome meant honey above all, and its use was as widespread as it was expected.

Because Romans had no access to cane sugar, their confections grew from what the region offered: honey, cheeses, thickened dairy, and grape must reduced to syrup. The transformation of grape must into syrup created another sweetening option, one that echoed through much of Mediterranean food history. With these elements, Rome formed a dessert tradition entirely distinct from the sugar-laden creations of later centuries.

Every treat originated from the land itself—vineyards, orchards, hives, and pastures—rather than overseas plantations that would influence later eras.

Sweet Makers in the Roman City

Sweet dishes were not confined to household kitchens. Urban centers supported specialists whose work focused on creating confections for the public. Their presence underscores a sophisticated demand for dessert-like foods, long before refined sugar made such professions common elsewhere.

These artisans crafted honeyed pastries, small cakes, and other delicacies tailored to city tastes. Their shops reflect a culinary world where sweets were not merely occasional offerings but part of the rhythms of urban life, available to those who wished to enjoy them beyond the domestic table.

Across the empire, simple combinations formed the basis of beloved treats. Soft cheeses mixed with honey produced dishes that soothed and satisfied, while baked preparations enriched with eggs and flour emerged from the same instinct for comforting sweetness.

These pairings stood at the heart of Roman dessert-making, echoing a Mediterranean habit of blending dairy with honey that long predated Rome and continued after it. Their appeal lay in harmony: richness tempered by sweetness, simplicity elevated by texture.

The place of Rome in dessert history forms one link in a chain stretching backward into the ancient Near East and forward to the confections of the medieval Islamic world. Techniques Romans inherited from earlier cultures would one day evolve under the influence of sugar, producing desserts unimagined in antiquity. Yet for centuries, the Roman form of sweetness remained rooted in the land and the hive, in the natural abundance that allowed an empire to finish its meals with flavors both elemental and luxurious. (“Sweet invention. A history of dessert” by Michael Krondl)

Alongside these simple combinations of honey, dairy, and nuts, there existed another, more fragile world of skill: the art of pastry, of which only fragments now remain.

Reconstructing Rome’s Lost Pastry Tradition

Any attempt to understand pastry in the ancient world immediately encounters the greatest gap in classical cookery: almost the entire literature of ancient patissiers has vanished. What remains are scattered remarks from writers who reveal only glimpses of a once-flourishing tradition.

References to desserts made of fresh and dried fruit appear in Columella and Pliny. Martial speaks of a final course offered to Toranius—overripe grapes, Syrian pears, roasted chestnuts from Naples, Picenian olives, hot chickpeas, and wine. Alexander’s circle is said to have dipped fruits and nuts into gold for their dessert, while Trimalchio’s ingenious cook presented pastries stuffed with raisins and nuts, alongside quinces adorned with thorns to resemble sea urchins, as the spectacular conclusion of a banquet.

Many dinners ended with wine alone, which technically transformed them into drinking parties—comissationes, convivia, or symposia. Because many ancient wines were naturally sweet or enhanced with honey, such a drink could suffice as a satisfying final taste. Yet this did not mean the ancients refrained from solid sweets.

Passages preserved by Athenaeus suggest that pastry making was a developed craft, practiced by skilled culinary technicians and enjoyed widely by diners. That modern readers are often left with the impression that Greco-Roman desserts consisted only of fruit, nuts, wine, and vague mentions of “cakes” reflects the near-total disappearance of a large corpus of pastry cookbooks that once circulated in domestic kitchens and libraries.

Several authors wrote dedicated manuals: Aegimus, Hegesippus, Metrobius, and Phaestus each composed works titled Artopoiētikon (“Pastry Cookbook”). Chrysippus of Tyana included pastry preparations within his treatise on bread.

Numerous general cookery authors—Glaucus of Locris, Mithaecus, Dionysius, Heracleides of Syracuse, Agis of Syracuse, Epainetus, Hegesippus, Erasistratus, Euthydemus, Crito, Stephanus, Archytas, Acestius, Acesias, Diocles, Philistion, among others—likely included pastry material that is now lost.

Only one Roman cookbook survives intact enough to offer support: the De Re Coquinaria attributed to Apicius. It mentions several types of pastry—tracta and laganum—as components in various dishes. Apicius also records two flour-based sweets in which cubes of wheat bread or African must-bread are soaked in milk, baked, and then drenched in honey.

Other Roman agricultural writers preserve additional examples. Cato and Varro give recipes for globi, round preparations of cheese, flour, honey, poppy seed, and oil. Cato also records several other pastries, including placenta, spira, scriblita, encitum, erneum, spirita, savillum, and libum.

Varro mentions circuli and thrion, while Athenaeus cites several unnamed sweets. To create a full picture of ancient pastry would require a massive study of Cato, Varro, Apicius, Petronius, Horace, Martial, Plautus, Aristophanes, Athenaeus, the lost cookbooks, and most of the comic poets of Greece and Rome.

Even then, the absence of the celebrated pastry manuals by authors like Aegimus or Metrobius would prevent any reconstruction from being complete. For now, only modest conclusions are possible, for the surviving material is too fragmentary.

From this limited evidence, one type of dough—tracta—can be studied with some clarity, thanks especially to a detailed recipe in Cato.

Cato’s Recipe for Tracta and the Structure of Roman Pastry

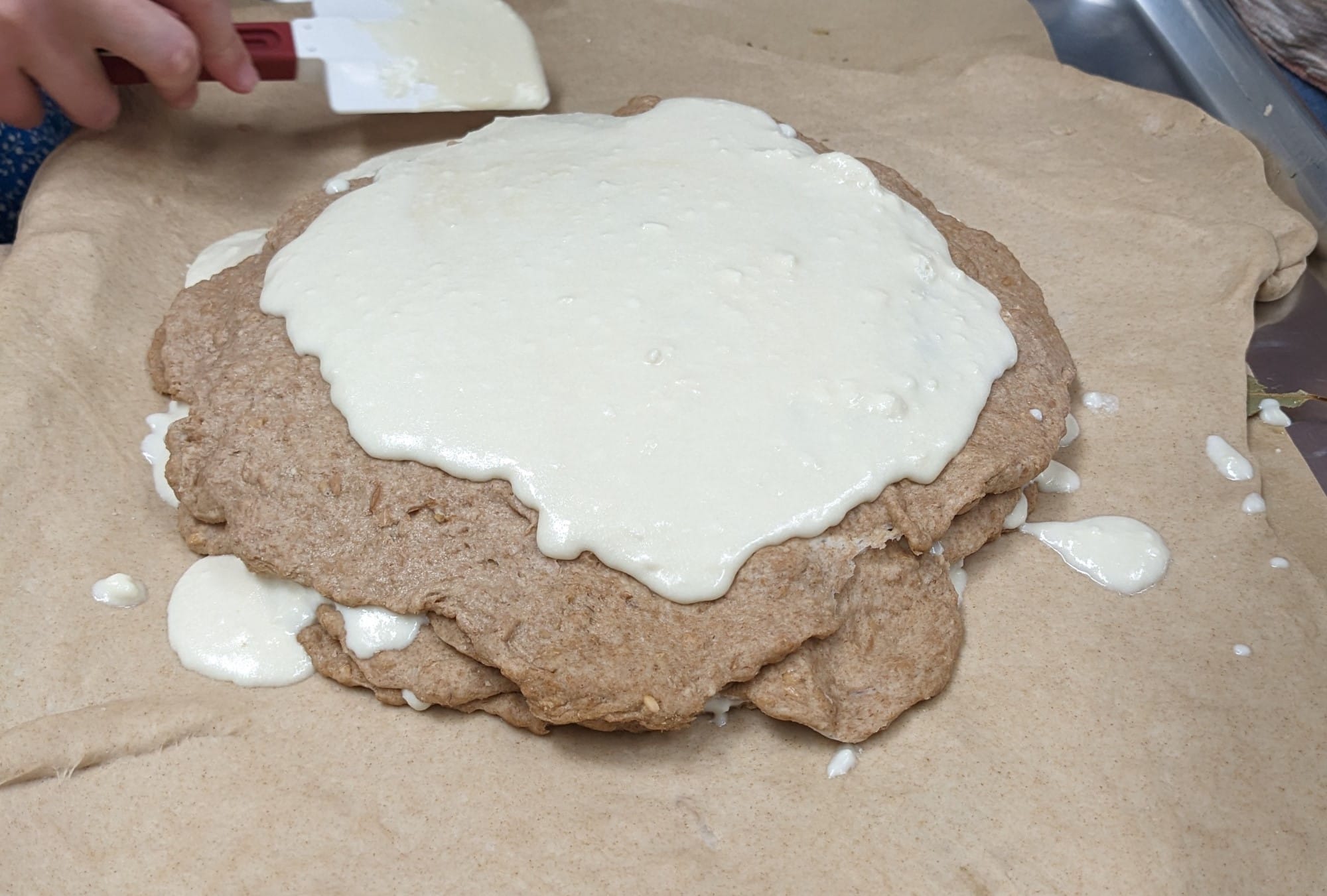

Cato’s most extensive instructions for tracta appear within his recipe for placenta.

“Make placenta as follows. Take 2 pounds of fine wheat flour to form the base layer. For the tracta, take 4 pounds of flour and 2 pounds of the finest alica. Pour water over the alica. When it has become very soft, place it in a clean mortar and dry it well. Then knead it thoroughly. When it is well worked, add the 4 pounds of flour gradually. From this mixture make the tracta. Place them in a basket so that they may “arescant.” When they have “arescant,” arrange them evenly.

When you shape each tracta, after kneading it, touch it with a cloth dipped in oil, wipe it, and lightly oil it. … Place each tracta in turn onto the base layer, spreading the cheese-and-honey mixture between them as you go, until all the cheese and honey is used. Place a final tracta on top. Then gather the edges of the base layer around it, arrange the fire, and set the placenta under a hot cover with coals above and around. When it is cooked, remove it and anoint it with honey.”

Interpreting Cato’s Instructions for Tracta

Cato calls for fine flour and very small-grained alica, which is to be soaked until soft, then placed in a mortar. The phrase “dry it well” (siccatoque bene) has caused difficulty: mortars had no holes, so the instruction cannot mean “drain through.” More likely, the softened alica was drained and then placed in the mortar to be worked until smooth.

Flour is added gradually, forming a kneadable dough. From this dough, the cook forms tracta and places them in a basket so they may arescant.

The traditional translation of arescant as “dry” creates technical problems. If the dough were brushed with oil before drying, it would remain moist and not dry properly. If it dried completely, it would later be impossible to stretch and would certainly crack.

A more practical understanding—consistent with how flour-and-water dough behaves—is to interpret arescant as “let them rest.” When dough rests, moisture distributes itself evenly, gluten relaxes, and the surface becomes smoother. This process can be described metaphorically as both “resting” and “drying,” since the tackiness of freshly kneaded dough diminishes.

If the tracta rest and are then oiled, they can be pulled or stretched into thin sheets. The layers must be flat and extremely thin; otherwise they would not bake properly when stacked inside a placenta. The very name placenta (from Greek πλακοῦς, “flat cake”) supports this thin, flat structure. So does the word tracta, which appears derived from trahere (“to pull”), implying dough that is pulled or stretched out—much as strudel or phyllo is stretched by hand today.

Other Forms and Uses of Tracta

Cato shows that tracta were not limited to one form. In his recipe for spira, which uses the same ingredients as placenta but is shaped differently, a tracta brushed with honey is stretched out “like a rope” (restim tractes facito) and placed on the upper crust, forming a coil that gives the pastry its name. This instruction reveals that tracta could not have been fully dried, for stretching a dried sheet would cause it to break. A rested, oiled sheet, however, stretches readily.

A related variation, spaerita, employs large balls the size of a fist (sphaeras pugnum altas) made from tracta, cheese, and honey. These are placed atop the pastry. This description provides some sense of scale: even if stretched thinly, a workable tracta sheet suitable for rolling into such a ball cannot have been excessively large, perhaps around 30 cm across.

Athenaeus also preserves information about tracta, called kapyria, made with flour, wine, pepper, milk, and a small amount of oil or lard. The addition of wine and milk would increase moisture, requiring the cook to adjust the flour or water accordingly—something ancient cooks handled intuitively, since recipes rarely gave precise quantities. This flexibility, seen throughout ancient cookery, reflects a professional understanding of doughs whose correct consistency was known by feel rather than by measurement.

Thus far, the evidence reveals only one side of tracta: a flat dough used in several distinct ways—first, as thin layers arranged within pastries such as placenta, spira, scriblita, erneum, and spaerita; second, as dough shaped with honey and cheese to form decorative elements placed on top of pastries, as seen in spira and spaerita; and third, as dough cut into small pieces and fried, as in the catillus ornatus, where the same preparation appears under the name laganum.

Yet the ancient cook employed tracta in another direction altogether. Although the dough seems to have been prepared with essentially the same ingredients and by the same method, its purpose was entirely different. In this second use, tracta did not serve as a pastry component—neither as a layered sheet nor as a formed garnish—nor even as a fried delicacy. Instead, it was incorporated into sauces, where it functioned not as a dessert element but as a thickening agent poured over savory dishes.

Taken together, the scattered traces of Roman sweetness reveal a culinary world shaped by honey, fruit, nuts, cheeses, and a repertoire of pastries now mostly lost. What survives—whether in agricultural treatises, literary anecdotes, or the technical instructions of Cato—shows that dessert in Rome was neither incidental nor unsophisticated. It belonged to the rhythm of daily life, to ritual, and to the craft of cooks whose work rarely endured beyond the hearth. Through these remnants, the contours of a dessert tradition become visible, offering a view into tastes and techniques that once brought a gentle conclusion to Roman meals. ("Tracta": A Versatile Roman Pastry” by Jon Solomon)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: