A History Written to Be Believed

Not every account of the past aims to preserve memory alone. Some are crafted to impose order, meaning, and authority on events that resist easy explanation.

Rome had conquered the Mediterranean, but it had not yet mastered its own story. Its past existed in fragments—family traditions, ritual memory, partisan accounts—repeated often, questioned rarely, and understood unevenly beyond Italy. At the very moment when Rome stood at the center of the world, its origins remained contested, vulnerable to misunderstanding, and open to dismissal. It would take an outsider, trained in another intellectual tradition, to reorganize that past and present it in a form that could command trust.

A Greek Scholar in Augustan Rome

Dionysius, son of Alexander, was born at Halicarnassus sometime before 55 BCE. He arrived in Rome in 30 or 29 BCE, at the moment when Augustus Caesar brought the civil wars to an end. Once established in the city, Dionysius devoted himself to mastering Latin and quickly became embedded in Rome’s intellectual life, forming relationships with fellow scholars, pupils, and patrons. Alongside this activity, he composed a series of Greek works devoted to rhetoric and literary criticism.

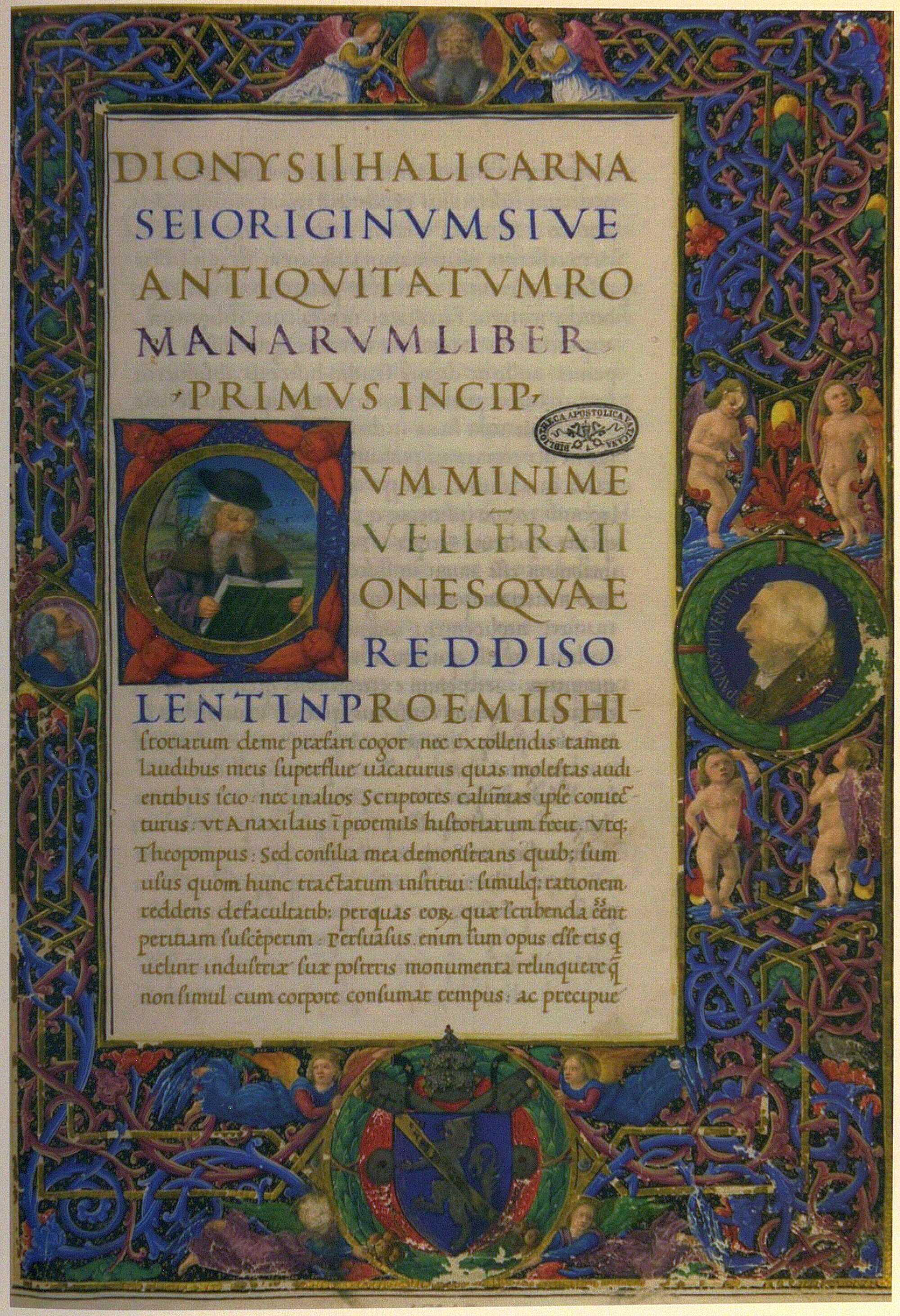

In 8 or 7 BCE, Dionysius published the opening portion of his major historical undertaking, Roman Antiquities. He appears to have remained in Rome for many years thereafter, continuing work on the remainder of the project. The history was ultimately conceived as a work of twenty books, tracing Rome’s past down to 264 BCE. Of this ambitious composition, the first eleven books survive, along with a number of later excerpts. The circumstances of Dionysius’ death, including its date and location, are unknown.

Beyond the Roman Antiquities, ten further works attributed to Dionysius have come down to us, and their relative chronology can be partially reconstructed. His earliest writings include On Imitation, preserved only in fragments and an epitome, and the initial section of On the Ancient Orators, which contains individual studies of Lysias, Isocrates, and Isaeus.

Works associated with a later phase include On Demosthenes, On Composition (also known as On the Arrangement of Words), the Letter to Pompeius, and the First Letter to Ammaeus. His final period is represented by On Thucydides and its appendix, the Second Letter to Ammaeus, and On Dinarchus. Two additional treatises, On Figures and On Political Philosophy, are known to have existed but have not survived.

Taken as a whole, Dionysius’ body of work reflects a sustained tension between cultural worlds and literary forms. His writings consistently move between Greek and Roman contexts, and between the practices of rhetorical criticism and historical narrative. This dual orientation shapes his intellectual project, in which his rhetorical and critical studies are closely bound to his account of Rome’s early history. Together, these strands reveal how his scholarship operated within—and responded to—the social, intellectual, literary, and political environment of Rome in the age of Augustus.

Rhetoric and History as a Single Intellectual Project

Modern scholarship has often treated Dionysius’ work as divided into two distinct domains. Despite frequent acknowledgment that his rhetorical criticism and historiography belong together, research has largely followed separate paths: some scholars focus on the Roman Antiquities, while others concentrate on the rhetorical and critical treatises.

More problematic than this division itself is the tendency for specialists in one area to overlook the findings and perspectives of the other. A central goal of recent interpretation has therefore been to reunite these strands, understanding Dionysius’ rhetorical criticism and his history of Rome as closely connected elements of a single, coherent intellectual and educational project.

From a modern standpoint, it may appear unusual that a single author devoted his life equally to rhetoric and historiography, disciplines now often seen as fundamentally different. In antiquity, however, the connection between the two was widely recognized. Any historical narrative necessarily involves invention—the selection of material—along with arrangement and style, which are the basic instruments of rhetoric.

The historian, no less than the orator, constructs a narrative by shaping and ordering events. In this sense, historical writing was understood as an act of composition closely related to forensic and deliberative speech.

In the Roman Antiquities, Dionyssius, does not merely recount Rome’s early history but presents exemplary figures whose conduct should serve as models. As he declares:

“Rome from the very beginning, immediately after its founding, produced infinite examples of virtue in men whose superiors, whether for piety or for justice or for life-long self-control or for warlike valor, no city, either Greek or barbarian, has ever produced.”

These figures are meant to shape the moral outlook of Dionysius’ readers, particularly Romans, by encouraging them to aspire to noble conduct:

“And again, both the present and future descendants of those godlike men will choose, not the pleasantest and easiest of lives, but rather the noblest and most ambitious, when they consider that all who are sprung from an illustrious origin ought to set a high value on themselves and indulge in no pursuit unworthy of their ancestors (μηδὲν ἀνάξιον ἐπιτηδεύειν τῶν προγόνων).”

For Dionysius, history must provide moral exempla. This conviction underpins his criticism of earlier historians. In the Letter to Pompeius, he contrasts Herodotus, whose Greeks perform “wonderful deeds,” with Thucydides, whose account centers on a war that was “neither glorious nor fortunate” and, in Dionysius’ view, scarcely worth remembering.

The principle of μίμησις is equally central to Dionysius’ rhetorical criticism. He examines the works of poets, orators, and historians in order to identify qualities worthy of emulation. The importance he assigned to imitation is underscored by his decision to devote a separate treatise to the subject, addressing its aims, techniques, and suitable models. Although On Imitation survives only in fragments, an epitome, and a substantial excerpt preserved elsewhere, the concept permeates all his writings.

In the preface to On the Ancient Orators, Dionysius presents classical Athenian rhetoric as the standard to be revived in Rome. He claims that after the decline brought about by “Asian” influence following the death of Alexander the Great, Attic eloquence had been restored under Roman leadership. As a result, he observes, many historical, political, and philosophical works were now being produced by “both Romans and Greeks” (καὶ Ῥωμαίοις καὶ Ἕλλησιν). Rome, in this vision, becomes a new Athens, fostering a renewed classical culture grounded in selective imitation of the past.

This emphasis on imitation extends beyond style to encompass moral and civic life. Dionysius frames his inquiry in explicitly ethical terms:

“Who are the most important of the ancient orators and historians? What manner of life and style of writing did they adopt? Which characteristic of each of them should we take over, or which should we avoid?”

By juxtaposing lifestyle and literary practice, Dionysius reveals a third level at which rhetoric and historiography converge: moral education. His work consistently promotes a form of παιδεία inspired by Isocrates, in which rhetorical training is inseparable from civic virtue. Readers of the Roman Antiquities are invited to become better citizens by reflecting on Rome’s early figures, just as readers of his rhetorical treatises are trained to participate responsibly in public life. As Dionysius asks in On Isocrates:

“Who could fail to become a patriotic supporter of democracy and a student of civic virtue after reading Isocrates’ Panegyricus? (…) What greater exhortation could there be, for individuals singly and collectively for whole communities, than the discourse On the Peace? (…) Who would not become a more responsible citizen after reading the Areopagiticus?”.

Across all his writings, Dionysius emerges as a committed teacher, concerned not only with technique, criticism, and historical narrative, but with virtue, civic responsibility, and the cultivation of human society. His vision of education—moral as well as intellectual—closely reflects the cultural and political concerns of Rome in the age of Augustus.

Between Greece and Rome: Identity, Culture, and Historical Vision

Dionysius’ writings stand as a key testimony to the complex negotiation of Greek and Roman identities at the end of the first century BCE. Greek authors living under Roman rule did not share a single, fixed sense of cultural identity. Literary works from across the Empire reveal a wide spectrum of responses to Roman power, shaped by genre, geography, audience, and intellectual tradition.

Some writers emphasized continuity with the classical Greek past, while others embraced the political and cultural transformations brought about by Roman rule and the new opportunities it created. Identity, in these texts, was neither static nor singular, but constructed and re-constructed through differing literary strategies.

A similar diversity of perspectives already existed among Greek authors of the Augustan period, who witnessed the emergence and consolidation of Roman imperial power. Because much Greek literature from this age survives only in fragments—or has been lost entirely—Dionysius of Halicarnassus occupies a particularly important position. Alongside figures such as Strabo of Amasia and Antipater of Thessalonica, he offers one of the fullest Greek perspectives on Rome during Augustus’ reign.

In many respects, Dionysius remains unmistakably Greek. He originated from Greek-speaking Asia Minor, wrote exclusively in Greek, and devoted much of his scholarly energy to the literature of archaic and classical Greece, from Homer to Demosthenes. His rhetorical criticism consistently privileges Attic oratory and historiography as models worthy of imitation.

More broadly, he displays a deep admiration for what he regarded as the finest achievements of Greek culture: the poetry of Pindar, the philosophy of Plato, the sculpture of Polyclitus, and the wider traditions of Greek music, art, and intellectual life. As a critic, he situates himself consciously within the Greek scholarly tradition, aligning his work with figures such as Isocrates, Aristotle, Theophrastus, Aristoxenus, and Chrysippus.

At the same time, Dionysius is thoroughly Roman in orientation. He arrived in Rome at a decisive historical moment and became fully bilingual, having, as he notes,

“learn[ed] the language of the Romans and acquir[ed] knowledge of their writings”.

His research drew on both Greek and Latin historical traditions. He consulted early Greek-language Roman historians such as Quintus Fabius Pictor and Lucius Cincius Alimentus, but he also read extensively in Latin historiography, naming authors including

“Porcius Cato, Quintus Fabius Maximus, Valerius Antias, Licinius Macer, the Aelii, Gellii and Calpurnii, and many others of note”.

Elsewhere he refers to Varro and additional Roman historians.

Dionysius’ engagement with Rome was not limited to texts. He emphasizes that part of his knowledge came from direct conversation:

“Some information I received orally from men of the greatest learning, with whom I associated” (οἷς εἰς ὁμιλίαν ἦλθον).

His social and intellectual network in Rome included both Greeks and Romans. Among his Greek associates were Demetrius, the addressee of On Imitation, and Caecilius of Caleacte, a prominent historian and rhetorician. Among his Roman connections was Metilius Rufus, to whom Dionysius dedicated On Composition as a birthday gift.

Dionysius describes Metilius’ father as his

“most esteemed friend”,

suggesting a relationship of patronage—an impression reinforced by the inclusion of the Metilii among the Alban principes. Metilius later became governor of Achaea, where he was able to put his teacher’s rhetorical principles into practice.

Another significant Roman connection was Quintus Aelius Tubero, the recipient of On Thucydides. Tubero himself wrote a history of Rome and belonged to an influential family known from Cicero’s Pro Ligario. Dionysius also corresponded with figures such as Ammaeus and Gnaeus Pompeius Geminus, whose precise cultural identities are unclear. What is evident, however, is that Dionysius was deeply embedded in Rome’s intellectual and elite social circles.

His work was shaped not only by scholarly exchange but also by relationships with families who appear to have supported and sustained his broader project.

Dionysius reflects explicitly on the relationship between Greece and Rome throughout his writings. In the preface to On the Ancient Orators, he praises Rome for fostering a cultural renewal, particularly for restoring the Attic Muse—symbol of morally serious and stylistically refined literature.

He credits Rome and its “leaders” with creating the political conditions under which great works could once again be produced in both Greek and Latin. Whether this praise is read as flattery or genuine appreciation, it situates Dionysius’ intellectual agenda firmly within the Roman context and invites reflection on how classical Greek models were meant to function within the political and cultural life of Augustan Rome.

The relationship between Greece and Rome forms the central theme of the Roman Antiquities. There Dionysius advances the striking claim that the earliest Romans were Greeks—living according to Greek customs, practicing Greek virtues, and governed by Greek institutions. He traces a sequence of five Greek migrations into Italy: Arcadian Aborigines; Thessalian Pelasgians; Arcadians led by Evander; Peloponnesians guided by Hercules; and Aeneas with the Trojans, whom Dionysius also classifies as Greeks.

Each group contributes to the gradual development of civilization in Italy. Pallantium, Lavinium, and Alba Longa mark stages in this process, culminating sixteen generations after Troy’s fall when the Latins enclosed Pallantium and

“called this settlement Rome, after Romulus”.

This narrative reaches its climax in Dionysius’ emphatic declaration of Rome’s Greek identity:

“Hence, from now on let the reader forever renounce the views of those who make Rome a retreat of barbarians, fugitives and vagabonds, and let him confidently affirm it to be a Greek city (Ἑλλάδα πόλιν), – which will be easy when he shows that it is at once the most hospitable and friendly of all cities, and when he bears in mind that the Aborigines were Oenotrians, and these in turn Arcadians (. . .).”

His portrayal of Roman institutions as fundamentally Greek—most fully articulated in the Constitution of Romulus —has long provoked skepticism and rejection. Yet more recent scholarship has responded with greater sympathy, particularly in light of archaeological and historical evidence for Greek influence on early Roman material culture. The question “Was Rome a polis?” has gained renewed relevance, and Dionysius’ thesis, though modified, has found partial support. As later scholars have observed:

“Greek culture leaves its mark on Rome at every moment we can document, and the more we learn about archaic Rome, the more we are inclined to accept, even if in a rather different sense, the argument of the Augustan historian, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, that Rome was from the first a Greek city.”

Dionysius and Augustus: Praise, Distance, and a Politics of Hints

Octavian—named as Augustus—appears only once across Dionysius’ surviving works, in a brief chronological marker: he says he came to Italy “at the very time that Augustus Caesar put an end to the civil war” (ἅμα τῷ καταλυθῆναι τὸν ἐμφύλιον πόλεμον ὑπὸ τοῦ Σεβαστοῦ Καίσαρος). That spare mention sits within a broader pattern: in the early Principate, many intellectuals from Greek-speaking regions moved to Rome, where elite interest in Greek teaching and scholarship created real opportunities for writers such as Strabo, Antipater, Caecilius, and Dionysius.

Their attitudes toward the new political order could differ widely—enthusiastic, critical, neutral, or simply complex—and in most cases the evidence does not allow certainty.

Where Dionysius’ Augustan setting has been discussed, scholarship long concentrated on whether he was “pro-” or “anti-” Augustan. The debate has often depended on selective reading, and it resembles older arguments once applied to Roman poetry.

Still, certain passages have repeatedly been used to map Dionysius’ political posture. On one side, his praise of Roman “leaders” (δυναστεύοντες) who are

“administer[ing] the state according to the highest principles” (ἀπὸ τοῦ κρατίστου τὰ κοινὰ διοικοῦντες,)

has been read as broadly affirmative toward the present order.

Even if these “leaders” are understood not as Augustus alone but as the aristocratic patrons who supported Greek culture, the opening of On the Ancient Orators clearly commends Roman administration for enabling literary production in Greek and Latin—an attitude that stands apart from the darker cultural pessimism of Longinus’ On the Sublime.

In Roman Antiquities Dionysius does not comment directly on Augustan policy, yet readers have identified indirect correspondences. One example is his praise of the Julian line:

“This house became the greatest and at the same time the most illustrious of any we know of, and produced the most distinguished commanders, whose virtues were so many proofs of their nobility.”

Other moments often placed in this orbit include his portrayals of Evander, Aeneas, Hercules, and Romulus—figures prominent in Octavian’s visual and ideological repertoire. More generally, Dionysius’ sustained attention to early Roman religion and morality, and his emphasis on virtues such as piety, justice, and moderation (εὐσέβεια, δικαιοσύνη, σωφροσύνη), have been seen as compatible with the moral register of Augustan reform. Even so, the older claim that Dionysius functioned as a mere conduit for Augustan propaganda—at the cost of “betraying” Greek culture—has been largely set aside.

Other passages have been used to argue for a sharper edge. A frequently cited example is Dionysius’ remark that ancient kings did not exercise power in the arbitrary manner found in his own time:

“the authority of the ancient kings (βασιλέων) was not self-willed (αὐθάδεις) and based on one single judgment (μονογνώμονες) as it is in our days” (οὐχ ὥσπερ ἐν τοῖς καθ᾿ ἡμᾶς χρόνοις).

It is not self-evident that this targets Augustus specifically; it could just as plausibly evoke the wider landscape of monarchic power that Rome had confronted. But it does underscore a central point: Roman Antiquities does not reduce cleanly to regime praise, and Dionysius’ work resists being read as a straightforward political pamphlet.

The rhetorical writings complicate matters further. Dionysius openly elevates classical Athens—the democracy that produced the Attic orators—and prefers Demosthenes not only as a master stylist but also as a remembered defender of democratic freedom. If Dionysius celebrates the Attic Muse’s return in Augustan Rome, he implicitly values not only literary and moral ideals but also political ones associated with Periclean and Demosthenic Athens.

That tension becomes easier to understand if the early Principate is treated as a period still forming rather than as a fixed, uniform “Augustan” system. Cultural life was dynamic, not monolithic; and Rome’s literary scene cannot be assumed to have been directly orchestrated by Augustus at every point.

In this light, Dionysius’ relation to Augustan Rome emerges as necessarily indirect and layered. What does seem firm is his strong investment in Rome—its structures, its past, and its intellectual environment—and a generally positive response to the way rhetorical and literary work could flourish under Roman rule. His classicizing programme, centered on Athenian exempla, aligned naturally with Roman elite interest in Greek culture and with broader eastern cultural currents often associated with the period.

At the same time, Dionysius repeatedly encourages readers to connect past and present through explicit signals of continuity and personal observation: he refers to rites

“which the Romans performed even in my time”,

notes

“the things that I myself know by having seen them”

and points to the hut of Romulus that

“remained even to my day on the Palatine hill” .

Yet his past-present relationship is not only continuity; it also includes contrast and development, as when he describes Pallantium’s destined transformation into imperial Rome:

“Yet this village was ordained by fate to excel in the course of time all other cities, whether Greek or barbarian, not only in size, but also in the majesty of its empire and in every other form of prosperity, and to be celebrated above them all as long as mortality shall endure.”

The familiar opposition between Greek and barbarian remains operative here. Dionysius’ world is still divided along those lines, and Rome is folded decisively into the Greek side of the equation. Rome is presented as Greek in origin and character—indeed, as possessing an exceptional “Greekness” among contemporary cities—even if that moral and cultural Greekness can be shown under strain in later narratives such as the Pyrrhic War.

Across genres, his broader project aims to affirm the durability of Greek civilization—rhetorical, literary, cultural, even political—so long as Rome continues to provide the conditions in which that project can thrive. ("Dionysius of Halicarnassus and Augustan Rome. Rhetoric, criticism and historiography" Edited by Richard Hunter and Casper C. de Jong)

By writing Rome’s beginnings as a coherent moral narrative rather than a loose collection of legends, Dionysius of Halicarnassus offered more than antiquarian reconstruction. He presented Rome with a usable past—one grounded in Greek cultural authority, ethical exempla, and rhetorical discipline. In doing so, he helped stabilize Roman identity at a moment of political transformation, not by inventing tradition, but by shaping it into a form that could be taught, imitated, and believed.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: