A Courtier’s View of Rome Without Illusions

A figure known through fragments, proximity, and performance offers a rare view into how Roman society operated when authority was informal and observation mattered more than power.

Not every Roman who understood power held office, commanded armies, or wrote laws. Some exercised influence more quietly, through judgement rather than authority, proximity rather than rank. They moved within elite circles, observed without intervening, and shaped values that others followed without noticing.

One such figure offers an unusually intimate view of Roman society – not as it wished to be remembered, but as it behaved when it assumed it was being watched only by itself. Yet that figure reaches us imperfectly, through fragments, scattered testimony, and later interpretation, demanding careful attention not only to what survives, but to how it has been preserved.

A Figure Preserved in Fragments

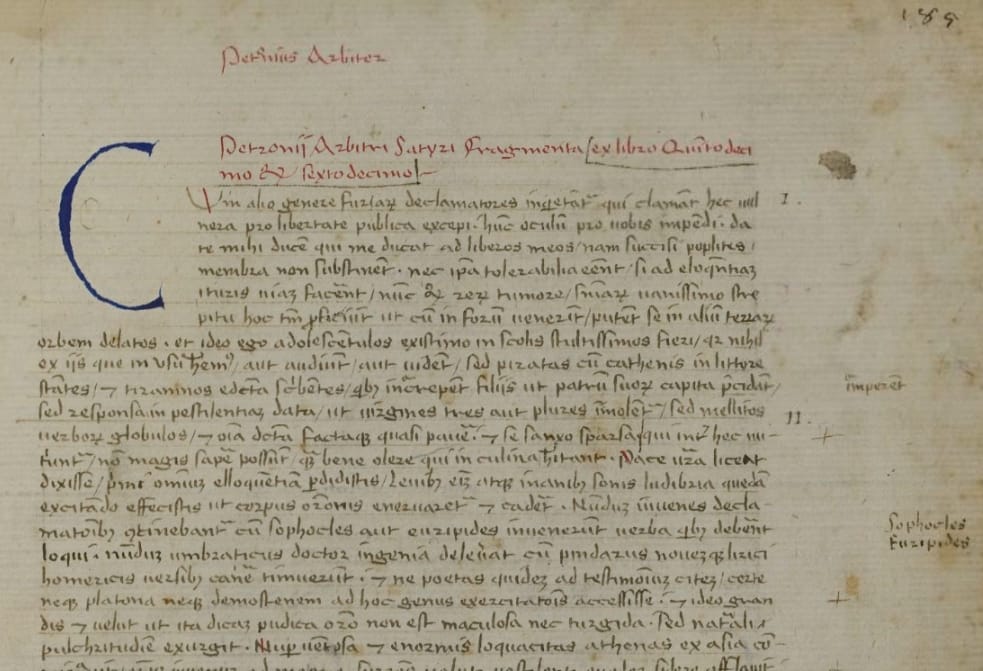

Petronius enters Roman history not as a stable authorial figure, but as a problem shaped by fragmentary texts, selective transmission, and a narrow set of ancient testimonies. What survives is enough to secure his importance, yet insufficient to resolve many of the questions that surround him. Modern understanding of Petronius has therefore developed not from a continuous narrative, but from sustained scholarly effort to reconstruct context, assess language, and trace reception across time.

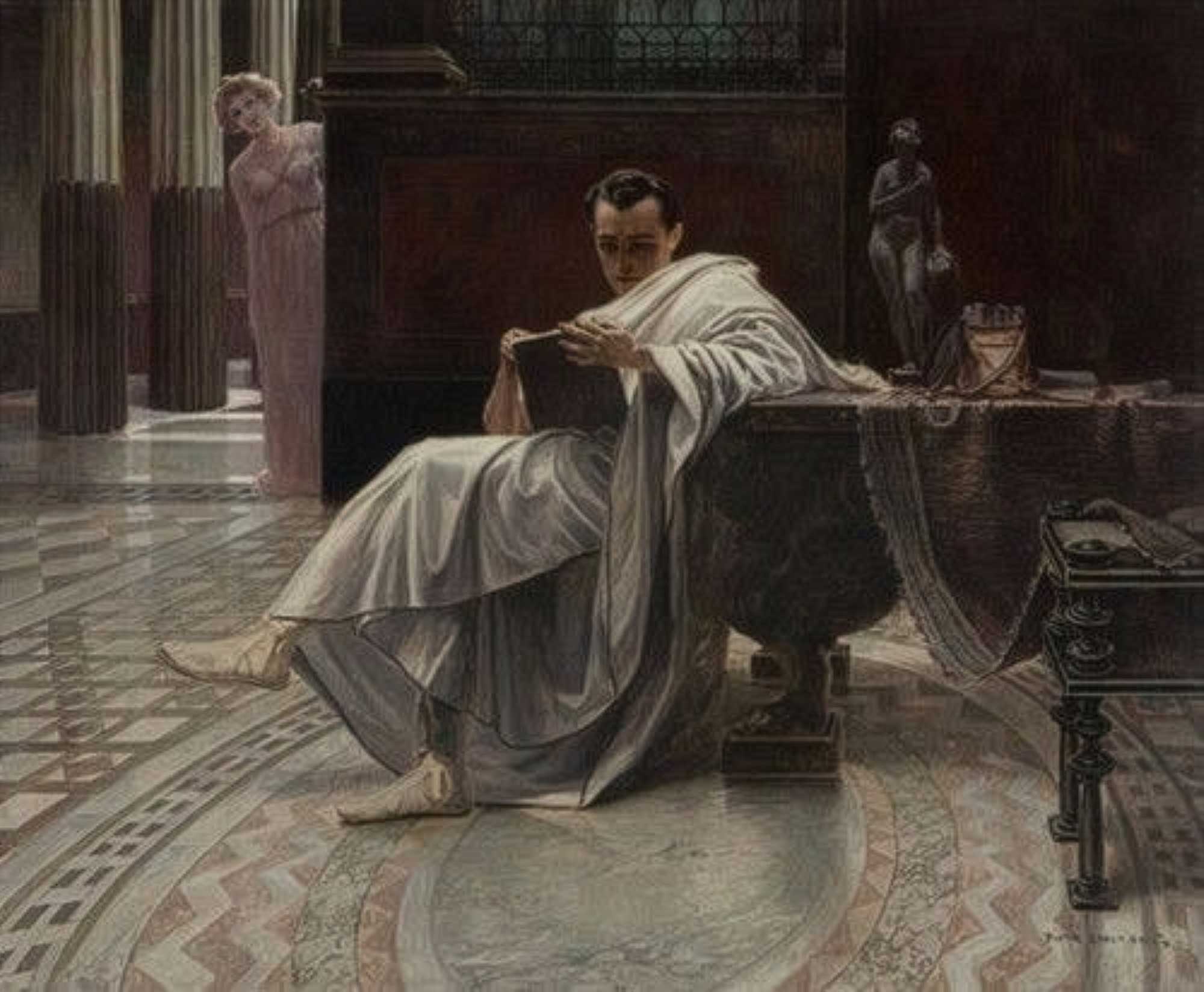

The ancient evidence itself already signals this uncertainty. Petronius is most vividly known through Tacitus, who places him within the court of Nero as a man valued not for moral rigor or political ambition, but for cultivated judgment and aesthetic authority. In Tacitus’ account, Petronius moves comfortably between leisure and responsibility, admired for discernment rather than severity. His reputation rests on taste, performance, and social intelligence rather than on public virtue in the traditional Roman sense.

“He passed his days in sleep, his nights in business and pleasure… yet he was not regarded as a wastrel or spendthrift, but as a man of polished ease.” (Tacitus, Annals)

This portrait has shaped scholarly engagement with Petronius from antiquity onward. It offers a historical anchor but also raises immediate questions. Tacitus does not identify Petronius as an author, nor does he comment directly on the Satyricon. The connection between the court figure and the surviving literary work is therefore inferred rather than explicitly attested. Much modern scholarship has been devoted to examining whether this identification is secure, how it should be understood, and what it implies for interpreting the text.

The literary work itself presents further challenges. The Satyricon survives only in fragments, preserved unevenly through manuscript tradition and later quotation. This incomplete state is not a marginal issue but a defining condition of interpretation. Questions of structure, narrative coherence, and genre cannot be addressed without acknowledging that large portions of the original composition are lost. As a result, scholarly analysis has focused as much on transmission and preservation as on content.

Ancient readers already recognized the distinctive nature of Petronius’ writing. The surviving episodes combine prose and verse, elevated literary allusion and colloquial speech, elite settings and marginal figures. No ancient source assigns the work a clear generic label, and modern attempts to classify it have remained provisional. It has been variously described as satire, novel, or a hybrid form that resists stable categorization. Rather than resolving this issue, scholarship has documented how the text itself invites such uncertainty.

Language has played a central role in this discussion. Particular attention has been given to Petronius’ rendering of social speech, especially in scenes that depict freedmen and non-elite environments. The realism of these passages has prompted extensive analysis of register, idiom, and literary artifice. Scholars have examined how linguistic variation functions within the narrative, not as accidental color, but as a deliberate literary technique.

The social world reflected in the text has also drawn sustained interest. The Satyricon offers glimpses of Roman life that differ markedly from senatorial histories or moral treatises. Wealth, consumption, status anxiety, performance, and ridicule appear as recurring features. These elements have encouraged scholars to situate Petronius within the cultural environment of the early Empire, particularly the court of Nero, where display and refinement carried political weight.

Tacitus’ account of Petronius’ death reinforced this association. His description emphasizes composure, aesthetic sensibility, and controlled performance even in suicide:

“He broke off his life neither by stoic firmness nor with a philosopher’s discourse, but while conversing lightly… listening to songs and verses.”(Tacitus, Annals)

This episode has often been read alongside the literary work, not as a key to interpretation, but as part of the broader image through which Petronius was remembered. The convergence of literary style and historical portrayal has encouraged scholars to treat Petronius as a figure whose identity is inseparable from questions of performance, taste, and cultural authority.

Beyond antiquity, the transmission of Petronius further shaped his reception. The text survived through selective preservation, moral excerpting, and later scholarly reconstruction. Medieval and early modern readers encountered Petronius not as a complete work, but as a collection of episodes, quotations, and curiosities. This process influenced how the Satyricon was read, classified, and valued, and it continues to affect modern editions and interpretations.

What emerges from this long scholarly engagement is not a settled portrait, but a carefully documented field of inquiry. Petronius remains a figure defined by fragments, mediated testimony, and competing lines of interpretation. Modern scholarship has approached him by mapping evidence, tracing transmission, and analyzing form rather than by imposing definitive conclusions. The result is a body of research that reflects the nature of its subject: partial, complex, and resistant to closure.

It is within this framework that any discussion of Petronius must begin—not with certainty, but with an awareness of how his text, his historical setting, and his afterlife have been understood, debated, and preserved. (“Mnemosyne. A bibliography of Petronius” by Gareth L. Schmeling & Johanna H. Stuckey)

What Remains When a Roman Text Stops Circulating

The fragmented state of the Satyricon is not the result of a single act of loss or suppression, but of a long and uneven process of transmission. In its original form, the work circulated on papyrus scrolls, a medium that was both fragile and impractical for texts of great length. Copying such works required time, expense, and sustained interest, conditions that were not consistently met as literary priorities shifted.

Evidence from Late Antiquity indicates that the Satyricon once survived in a more complete state than the one known today. Later authors refer to episodes and passages that are no longer extant, suggesting that the damage occurred not in the Roman period but much later. By the early Middle Ages, the work was no longer copied in full. Instead, excerpts were selected, rearranged, or omitted altogether, often according to the tastes, interests, or scruples of those handling the manuscripts.

The surviving text ultimately derives from a single damaged exemplar, itself no longer preserved. Different manuscript traditions show signs of selective transmission, with some passages shortened or excluded, particularly where subject matter was judged unsuitable. The result is a work that reaches the modern reader as a sequence of episodes rather than a continuous narrative, shaped as much by medieval copying practices as by its original design.

The fragmentary condition of the Satyricon therefore reflects patterns of preservation rather than authorial intention. What survives is not a deliberate selection, but the residue of a text that passed through centuries of partial copying, excerpting, and loss.

Speaking Like Epic, Living Without It

The Satyricon is marked by a distinctive narrative technique that repeatedly brings elevated literary forms into contact with scenes of physical immediacy and social instability. Characters frame their experiences in the language of epic, tragedy, and rhetorical display, only for those ambitions to be undercut by circumstance. Moments of high literary aspiration collapse into hunger, fear, bodily failure, or ridicule.

This pattern appears throughout the surviving text. The narrator repeatedly casts himself in heroic terms, borrowing the posture and vocabulary of epic protagonists, yet the situations he encounters offer no space for heroic resolution. Action gives way to confusion; resolve dissolves into improvisation. The effect is not achieved through parody alone, but through sustained tension between literary register and lived experience.

The technique relies on contrast rather than commentary. The text does not explain its own irony or guide the reader toward a moral position. Instead, it allows the mismatch between language and reality to remain visible. Epic diction is not mocked directly; it is simply shown to be inadequate to the world in which the characters move.

This method shapes the Satyricon as a narrative in which literary tradition is constantly present but never secure. The forms of the past are available, but they no longer guarantee meaning, authority, or coherence. What remains is a world governed by contingency, performance, and appetite, narrated in a language that continually reaches beyond its own reach.

A Name That Signals Authority Rather Than Identity

The author traditionally identified as Petronius is known to later sources as Arbiter, a designation associated with judgment, taste, and refinement rather than with family lineage. In the manuscripts, the term functions as a title rather than a cognomen, likely reflecting the role of an arbiter elegantiae, a figure consulted on matters of style and conduct.

Ancient testimony connects this Petronius with the court of Nero, where a man of that name appears as a figure of cultivated detachment and social authority. The identification of the author of the Satyricon with this courtier is widely accepted, but it cannot be proven with certainty. Ancient sources disagree on details of his name and career, and no surviving text explicitly confirms the connection.

What can be said is that the literary persona implied by the Satyricon aligns closely with the qualities attributed to such a figure: sensitivity to style, awareness of social performance, and a practiced distance from moral earnestness. The work does not speak from the margins of Roman society, nor from a position of formal authority, but from within elite circles that understood both the language of culture and its limits.

The name “Petronius Arbiter” thus functions less as a biographical anchor than as a point of convergence between literary voice and social role. It identifies a mode of observation rather than a secure historical identity.

Observing Power Without Claiming It

The world of the Satyricon corresponds closely to the social and cultural conditions of mid-first-century Italy. Its settings, references, and assumptions reflect a society shaped by mobility, display, and competitive self-presentation. Education, rhetoric, dining, and entertainment appear not as abstract institutions but as lived practices, embedded in daily interaction.

The text presupposes familiarity with elite schooling, declamatory habits, and literary models current in the early imperial period. At the same time, it registers tensions created by wealth without pedigree, learning without authority, and ambition without stable outcome. Social boundaries are present but porous, and status is continually asserted, tested, and revised.

Although later readers have often sought direct political commentary in the Satyricon, the surviving text does not adopt the language of opposition or reform. It does not argue against imperial power, nor does it seek to expose it. Instead, it reflects the conditions under which power was experienced indirectly, through proximity, imitation, and spectacle.

The Rome that emerges from the Satyricon is neither idealised nor systematically condemned. It is observed. The narrative records how people speak, compete, flatter, and fail within a world that rewards performance more reliably than virtue. In this sense, the work belongs fully to its time, shaped by the social realities of Nero’s reign without reducing them to commentary. (“The Satyrica of Petronius. An intermediate reader with commentary and guided review” by Beth Severy-Hoven)

What survives of the Satyricon offers no complete story and no stable viewpoint. Its value lies instead in what it preserves unintentionally: the texture of elite life, the fragility of literary authority, and the distance between cultural ideals and lived experience. Read in fragments, the work still reveals a Rome attentive to appearances, governed by proximity, and aware – often uncomfortably – of the limits of its own language.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: