The Roman Soldier's Shield that Never Returned Home

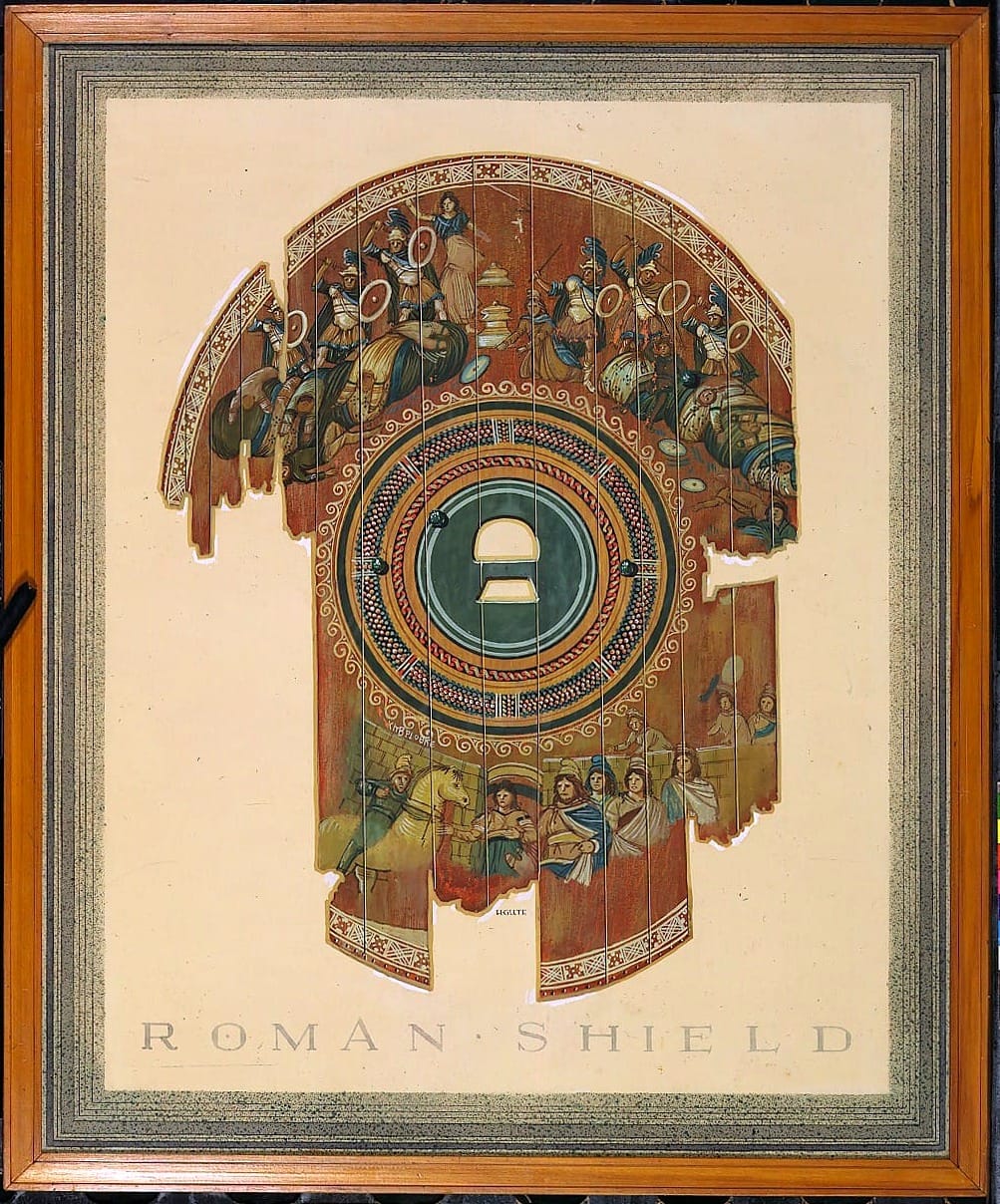

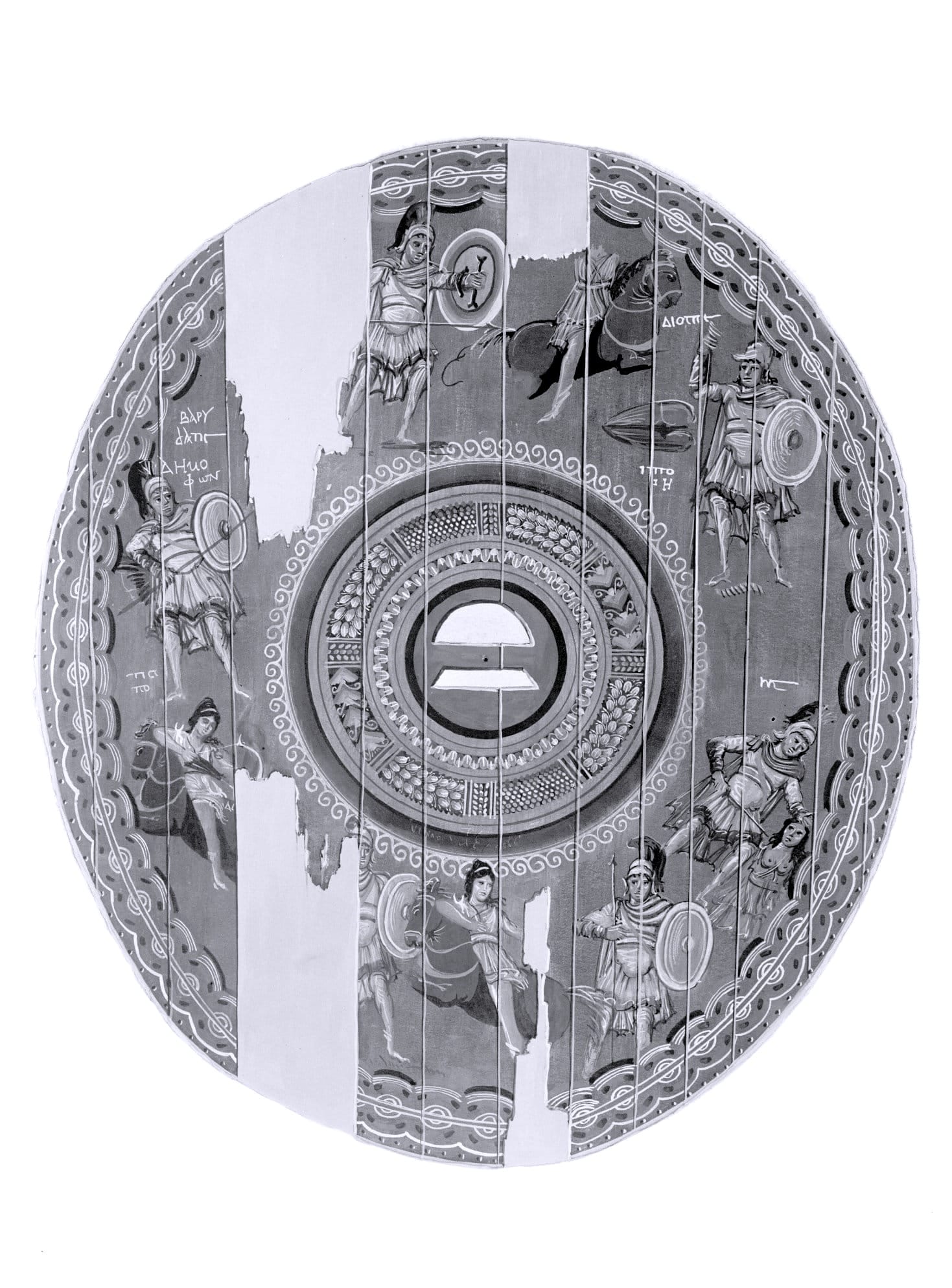

Discovered beneath the ruins of Dura-Europos, a group of painted Roman shields preserves rare evidence of military equipment, artistic practice, and frontier life on Rome’s eastern edge shortly before the city’s destruction in 256 CE.

In January 1935, during excavations at the eastern frontier city of Dura-Europos, archaeologists uncovered a small but unusual assemblage of military objects buried beneath the city’s final defensive works. Recorded carefully in the field diary of the excavation’s director, the find consisted of several wooden shields preserved in a state rarely encountered in Roman archaeology. At the time of their discovery, their significance was not yet fully apparent, but their context and condition would later prove to be exceptional.

When Painted Shields Emerged from the Sand at Dura-Europos

On Friday, January 18, 1935, Clark Hopkins, then field director of the excavations at Dura-Europos, recorded an extraordinary discovery in his field diary. As he noted:

“Just after breakfast, three painted shields were found one right a top of the other…. Herb and I spent all morning removing them. Most of the wood was strong enough to move easily and much of the painting is visible.”

The shields, uncovered stacked together beneath the ruins of the city, were later transferred to the collection of the Yale University Art Gallery. Dated to shortly before 256 CE—the year Dura-Europos fell to the Sasanian forces and was subsequently abandoned—they were immediately recognised as exceptional survivals. Painted wooden objects from antiquity are extremely rare, and these shields preserve substantial traces of their original decoration.

The finds from Dura-Europos preserve both traditional Roman body-shields and broader oval forms, and the painted examples belong to more than one of these shield traditions.

Their imagery draws directly on epic tradition. The painted surfaces depict scenes from the Trojan War as told in the Iliad, including combat between Greek warriors and Amazons, alongside the figure of a warrior god. Together, the shields offer rare material evidence for the visual culture of the Roman military on the empire’s eastern frontier, combining martial equipment with mythological imagery rendered in paint on wood. ("Painted Roman Wood Shields from Dura-Europos" by Anne Gunnison, Irma Passeri, Erin Mysak and Lisa R. Brody, in Mummy Portraits of Roman Egypt)

The Roman Body-Shield in Practice

The best-preserved shield from Dura-Europos belongs to a long-established Roman tradition of large, curved body-shields used by heavy infantry. By the mid-third century CE, this form was still in active service, particularly in the eastern provinces, where its size and curvature offered effective protection against missiles as well as in close-order combat.

Ancient authors emphasised both its construction and its tactical value. Polybius describes a shield made from layered wooden boards, reinforced at the edges and fitted with a central iron boss to deflect blows and missiles, its convex form allowing it to absorb impact more effectively than a flat surface. Archaeological evidence from Dura confirms many of these features in practice, though it also reveals variation in materials, assembly techniques, and surface treatment that literary sources alone cannot capture.

The Dura example was constructed from thin wooden strips arranged in multiple layers, producing a lightweight but resilient structure. Its curved profile would have shielded the bearer from shoulder to knee, while the missing central boss once protected the hand gripping the shield from behind. Traces of fabric, skin, and painted decoration show that the shield was not only functional but also visually striking, its surface serving as a field for symbolic imagery as well as identification.

Rather than representing an outdated or ceremonial object, the survival of such a shield at Dura demonstrates the continued relevance of the Roman body-shield at a moment when equipment traditions were becoming increasingly fluid. Alongside lighter oval forms and regionally influenced designs, it reflects a military environment in which established Roman practices coexisted with adaptation to local conditions and tactical needs.

Ancient descriptions provide a technical account of the shield’s construction and intended use.

The Roman panoply consists firstly of a shield (scutum), the convex surface of which measures two and a half feet in width and four feet in length, the thickness at the rim being a palm's breadth. It is made of two planks glued together, the outer surface being then covered first with canvas and then with calf-skin. Its upper and lower rims are strengthened by an iron edging which protects it from descending blows and from injury when rested on the ground. It also has an iron boss (umbo) fixed to it which turns aside the most formidable blows of stones, pikes, and heavy missiles in general. Polybius, The Histories.

A Frontier City Shaped by Empire and Army

Perched above the Euphrates in eastern Syria, the ancient city of Dura-Europos (modern Salhiyeh) has, for over a century, offered one of the clearest archaeological views into life in the Parthian and Roman Middle East. Founded as a Hellenistic military settlement, the city developed under Arsacid control into a small but complex urban centre. Its ruling elite was Greek-speaking, while much of the wider population spoke Aramaic.

Around the middle of the second century CE, Dura entered the Roman sphere and remained there until its destruction and abandonment around 256 CE following a Sasanian siege.

Crucially, the site was never reoccupied. This meant that once Dura was identified in 1920, its remains were unusually well preserved and readily accessible for archaeological investigation. Large-scale excavations conducted between the two World Wars brought the city international attention. Papyri, inscriptions, and extensive wall paintings—including those from temples, an early Christian church, and a synagogue—revealed a densely layered religious and cultural landscape rarely preserved elsewhere in the Roman world.

During its final phase, Dura also housed a substantial Roman imperial garrison. This force established a large military base in the northern sector of the city, an area that may have occupied as much as a quarter of the walled urban space. Although portions of this base were uncovered during excavations in the 1930s, it was never systematically analysed or fully published.

Yet it represents a rare and valuable example of a Roman urban cantonment—distinct from the more familiar rectangular forts of the European provinces—and therefore holds particular significance for the study of Roman military organisation under the Principate.

Subsequent reassessment has shown that the military presence at Dura was both larger and earlier than previously assumed. Rather than being a development confined to the years around 210 CE, the base appears to have expanded substantially several decades earlier. Independent analysis of documentary evidence concerning the size and composition of the garrison supports this conclusion, indicating that Roman forces grew significantly in the later second century rather than the early third.

This revised chronology has broader implications for the city’s political history, especially for theories proposing a Palmyrene protectorate over Dura during this period, which now appear less convincing.

Equally important is the recognition of a large population of military dependents—family members, servants, and others connected to the garrison—who formed part of an extended military community. The Roman presence was therefore not limited to soldiers alone. Instead, it functioned as a “city within a city,” reshaping the social and economic fabric of Dura to a greater extent than previously acknowledged.

Earlier interpretations have alternated between viewing the garrison as an oppressive occupying force or as a driver of economic growth and civilian–military integration. The exceptional combination of archaeological and textual evidence from Dura allows for a more nuanced assessment. Rather than a single, uniform impact, the Roman military presence produced complex and shifting patterns of interaction, creating both opportunities and tensions across different levels of society. These dynamics unfolded against the backdrop of wider imperial conflicts that would ultimately bring the city’s history to an abrupt end. ("The Roman military base at Dura-Europos Syria. An archaeological visualization" by Simon James)

The Scutum at Dura-Europos

The scutum reflects a design optimized for close-order combat and bodily protection. Its semicylindrical form provided extended coverage from shoulder to knee, particularly suited to dense infantry formations. Unlike the flat shields of their adversaries, the scutum offered enhanced protection, allowing Roman soldiers to form the Testudo formation, a defensive tactic likened to a tortoise shell that was nearly impervious to arrows and projectiles.

The scutum, characterized by its rectangular, curved design, measures 105.5 by 41 cm and is predominantly constructed from wood. Discovered fragmented into thirteen pieces, it is composed of wooden strips ranging from 30 to 80 mm in width and 1.5 to 2 mm in thickness. These strips are assembled in three layers, culminating in a total wood thickness of 4.5 to 6 mm. At the shield's center is a hole, likely made post-construction, with the umbo (central boss) now missing, along with the original shield hump.

The shield's rear was initially reinforced with wooden strips, which have since been lost, and it is believed to have been covered with a red skin, as noted in the initial excavation report, though this covering has since disappeared. The front surface was layered with fabric and then either skin or parchment, adorned with a painting. Surrounding the central hole are various decorative bands, featuring motifs such as an eagle within a laurel wreath, winged Victories, and a lion.

The Shields at Dura-Europos

The excavations at Dura-Europos produced the most substantial body of archaeological evidence for Roman shields yet recovered from a single site. The Yale collections and excavation archives preserve shield bosses, wooden boards, reinforcing bars, and a large number of fragments, amounting to the remains of as many as fifty individual shields. No other Roman site has yielded such a concentration of shield-boards, let alone examples retaining traces of painted decoration.

At the same time, the assemblage is incomplete and unevenly preserved. No shield was found fully intact, and many fragments mentioned in the excavation reports can no longer be located. Any interpretation must therefore balance the richness of the surviving material against the gaps created by loss, decay, and early excavation practices.

Shield Types in Use at Dura

Archaeological evidence from Dura indicates the presence of at least four distinct shield traditions. The most common form is the large, broad oval shield constructed from thin vertical planks of wood and fitted with a central grip protected by a metal boss. These shields dominate the surviving assemblage and appear to represent the standard Roman fighting shield in use at the site during its final decades.

A second form is the semicylindrical plywood shield. Constructed from layered wooden strips glued with alternating grain directions, this shield belongs to the long-established Roman tradition of the legionary body-shield. Its survival at Dura into the mid-third century demonstrates that this form had not yet disappeared from active use, at least in the eastern provinces.

A third, rarer type consists of oval shields oriented horizontally and lacking a central boss. Known only from drawings and brief descriptions, these examples are difficult to classify. Their construction and decoration suggest a connection with Roman shield-making, yet their form departs from standard imperial types and may reflect adaptation to local traditions.

Finally, a group of shields constructed from rawhide threaded with wooden sticks represents a completely different technological tradition. These shields, lightweight and rigid once dried, have close parallels in Near Eastern military practice stretching back centuries. Their presence at Dura complicates attribution, as they could have belonged to Roman troops, local levies, or Sasanian forces involved in the siege.

Many shield fragments described in early excavation reports are no longer traceable in the Yale collections, making verification impossible. Particularly important are the painted shield fragments which were described in detail but have since vanished. Their dimensions and decoration closely match the oval plank shields recovered in later seasons, suggesting that painted shields were once even more numerous than the surviving material indicates. The repeated appearance of shield fragments in different contexts across the city reinforces the impression that shields were widely used, repaired, discarded, and repurposed in Dura’s final years.

Depictions of shields in Dura’s wall paintings and reliefs introduce further complexity. Large oval shields, smaller hexagonal forms, and circular targes appear in religious and civic art, particularly in the synagogue and in Palmyrene contexts. Gods are often shown carrying oval shields or small round bucklers, while mounted figures in local dress frequently bear bossless shields.

None of the small targes seen in art have been recovered archaeologically, but the bossless ovals may represent Romanised versions of this regional type. The coexistence of these images with the archaeological material points to a diverse visual and functional shield culture rather than a single uniform standard.

Building the Broad Oval Plank Shields

The construction of the oval plank shields reveals a high degree of technical sophistication. Thin planks of poplar were glued edge to edge and shaped into a broad oval, with the thickness carefully graduated from centre to rim. The finished board was slightly domed, a form that greatly increased rigidity without adding weight. Tool marks show the use of sharp axes, adzes, and planes, and the final outline was trimmed only after the board had been fully shaped.

Openings for the central grip were cut after assembly, leaving a wooden core that was reinforced by a transverse iron bar on the reverse. This iron bar served both as a grip and as a structural brace, spreading stress across the board. Leather edging, stitched through holes near the rim, protected the vulnerable edges from wear and impact.

Two main surface treatments were used on the oval shields. Some were faced with very thin animal skin glued to both sides of the board, with a layer of fibrous material embedded in the adhesive to prevent splitting along the grain. Others were prepared with gesso, sometimes applied over fabric or fibre, creating a smooth surface suitable for painting. These methods reveal a clear concern with durability as well as appearance.

Painted decoration survives in varying degrees, and analysis shows that several painting media were employed, including water-based paints, tempera, and casein. The rectangular shield from was painted using an encaustic technique, similar to that used in Egyptian mummy portraits, producing a waxy, weather-resistant surface. Pigments included vermilion, carbon black, earth colours, and indigo.

The shield designs from Dura fall into several broad categories. Some consist of concentric bands arranged around the boss, often with wreath-like motifs and strong radial symmetry. Others feature large central figures, including mythological scenes drawn from Greek epic. A third group employs bold geometric patterns, including spoked designs with repeated heart-shaped motifs. These designs echo second-century auxiliary shield imagery while anticipating the bold, simplified patterns seen in late Roman art and the Notitia Dignitatum.

The diversity of decoration raises questions about function. Shields bearing complex mythological scenes are unlikely to have been standard battlefield equipment for entire units. They may represent parade shields, training equipment used in cavalry exercises, or personal display pieces. Simpler designs, particularly those with strong geometric structure, are more plausibly connected with unit or cohort identity. Literary sources from Late Antiquity confirm that shield patterns could serve as identifiers, though the extent of standardisation remains unclear. ("Excavations at Dura-Europos 1928-1937. Final Report VII. The Arms and Armour and other Military Equipment" by Simon James)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: