Tertullian: Rome’s Most Uncomfortable Christian

A lawyer, polemicist, and theologian, Tertullian confronted Rome with a Christianity that refused compromise. His writings reveal how early Christian demands for tolerance coexisted with sharp limits, rigid boundaries, and an uncompromising claim to truth.

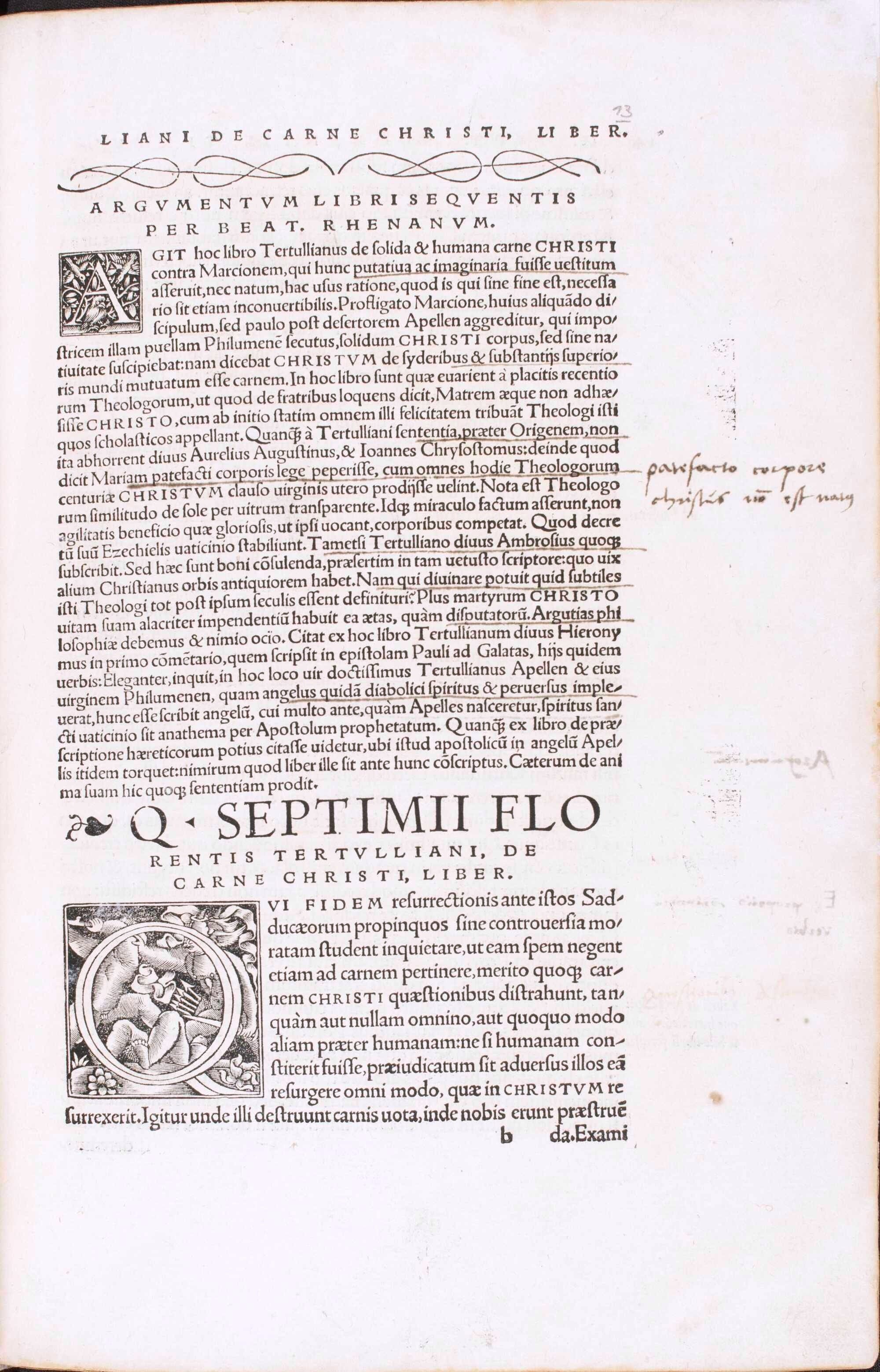

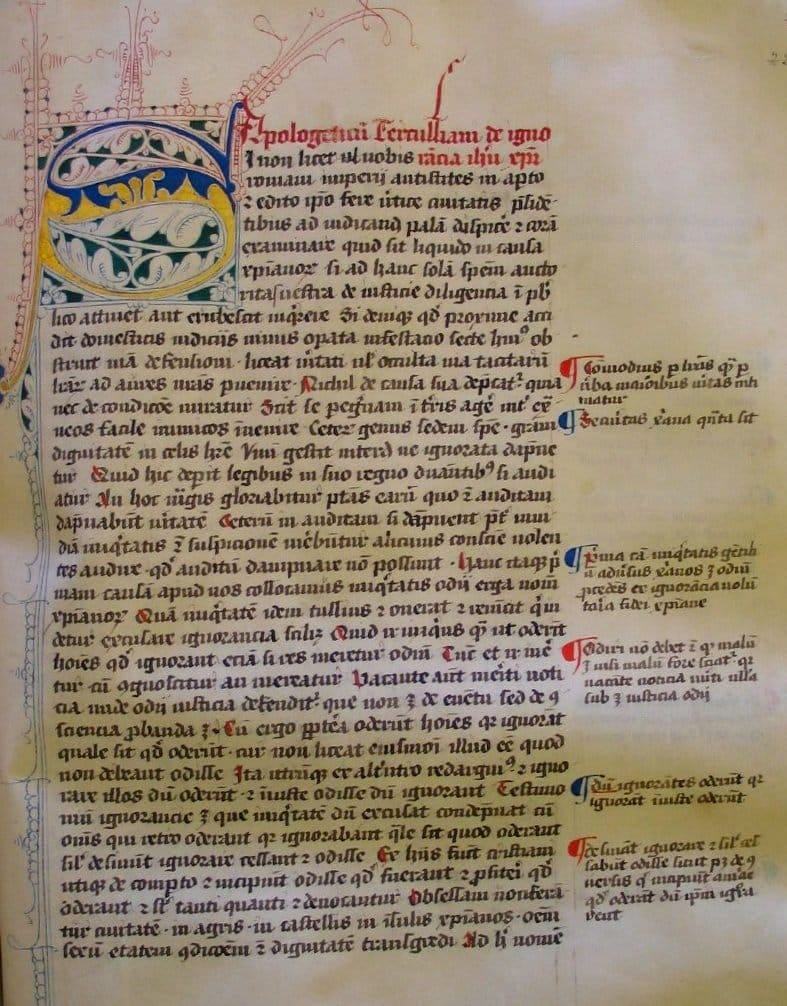

Christianity did not enter the Roman world quietly. It arrived argued, contested, and judged – in courts, in pamphlets, and in the language of Roman law itself. Few figures embody that confrontation more sharply than Tertullian. Writing from Roman Carthage at the turn of the third century, he spoke as an insider trained in rhetoric and law, yet as a believer increasingly unwilling to accommodate the assumptions of Roman society. His works do not seek compromise. They press, accuse, and unsettle – exposing the tension between a faith that demanded absolute loyalty and an empire that expected obedience above all else.

More than any other early Christian writer, Tertullian forced Rome to confront Christianity on its own legal and moral terms.

Tertullian and the Discipline of Belief

Tertullian of Carthage stands out as the first Christian thinker to develop theology in a systematic and intellectually self-aware way. Gifted with sharp wit and rhetorical force, he emerged as a formidable apologist, defending Christians against the hostility of Roman authority. Within the Christian community, his attention turned to the rule of faith as the standard by which truth could be recognised, a standard he believed was grounded firmly in the Gospel itself.

For Tertullian, theology could never be separated from conduct; failure of discipline was evidence of deeper spiritual error.

For him, the coherence of the divine plan of salvation reached its fulfilment in Jesus Christ, the Son of God and crucified saviour. Yet when this theological vision was measured against the lived conduct of believers, he was struck by what he saw as moral weakness and compromise. From this disappointment followed a renewed emphasis on original sin, the necessity of fearing God, and an expectation of imminent judgement.

As a result, Tertullian has proved difficult for modern readers to accommodate. Both liberal Christianity and its secular critics have tended to set him aside, shaped as they were by Enlightenment assumptions that reason should culminate in orderly, almost mathematical systems of thought. The erosion of that confidence in reason by later thinkers has reopened the possibility of reading Tertullian on his own terms: as a writer drawn to tension rather than harmony, to contingency rather than system, and to argument sharpened by paradox rather than resolved by abstraction.

Simplicity as the Mark of Truth

For Tertullian, simplicity is not intellectual weakness but the primary sign of divine truth. Against accusations that Christians were secretive or sinister, he insisted that what appeared hidden was, in fact, plain. Christian faith possessed a simplicity that stood in contrast to the elaborate rituals and speculative excesses of pagan religion.

By “simplicity,” Tertullian meant not ease, but undiluted truth – belief stripped of philosophical ornament.

Drawing on the Pauline language of the mystery of salvation, Tertullian argued that God’s wisdom is not concealed through complexity but revealed through clarity. Truth, when left undistorted, is simple; it becomes confused only when human opinion intervenes.

This simplicity is most clearly expressed in baptism. For Tertullian, baptism marks the beginning of life itself – a decisive break with original blindness and the entrance into salvation. Its outward plainness is precisely what provokes scepticism: water, words, and immersion appear inadequate to achieve eternal life. Yet this very simplicity reveals divine power.

God achieves the greatest transformation through the least ostentation, confounding worldly expectations. Still, Tertullian warned that simplicity without understanding could become vulnerability; faith required instruction and discipline to guard it from distortion.

Divine Power Revealed Through Weakness

Tertullian repeatedly returned to the paradox that God’s strength operates through what appears weak or foolish. Drawing on Pauline and Stoic traditions, he argued that divine wisdom takes form in opposition to human standards of power. Christians, whom he famously described as “little fishes,” survive only within the waters of baptism.

Faith contracts itself into the simplest confession – Jesus Christ, Son of God, Saviour – yet this reduction contains the fullness of salvation. Repetition, brevity, and restraint reinforce truth rather than diminish it.

Christian simplicity did not require withdrawal from society. Believers lived, worked, married, traded, and served alongside others while refusing participation in public cults. Their daily conduct mirrored their faith: modest dress, restrained behaviour, and rejection of luxury. This simplicity reflected acceptance of the created world as God’s work, not contempt for it. Christians followed a new aesthetic rooted in moral clarity rather than social display.

Tertullian recognised that a passion for simplicity could lead to excess. His polemical style sometimes sacrificed nuance for force, and his insistence on conscience over institutional authority led to conflict within the Church. His account of divine justice leaned heavily on retribution, and his arguments could appear severe.

Theology, like philosophy, risks distortion when complexity is cut too aggressively. Debate requires argument, not merely silencing opposition, and simplicity must not become rigidity.

One God and the Unity of Salvation

Against Marcion, Tertullian defended the unity of God and the continuity of creation and redemption. God’s simplicity meant oneness, not division. Any attempt to separate the creator from the saviour fractured that unity and multiplied contradictions. Salvation that redeemed only the soul but not the body was, in his view, incomplete.

True goodness must save wholly. The same God who created the world also restored it, and divine justice served divine goodness rather than opposing it.

All simplicity finds its fulfilment in Christ. The confession Jesus Christ, Son of God, Saviour condensed the entire economy of salvation into a single formula. In Christ, creation is corrected, history fulfilled, and death overcome. His victory was not military but spiritual, achieved through humility and the cross. What appeared dishonourable became the means of perfection. Salvation unfolded as a continuation of creation, not its negation, culminating in the recapitulation of all things in Christ.

Brevity, Paradox, and Continuity

Tertullian valued brevity because truth did not require ornament. Scripture, Stoic philosophy, and Christian proclamation converged in their preference for concision. Paradox was not a flaw but a necessary form of expression for divine realities. Though his arguments could appear fragmented, they were held together by a single concern: the perfection of God’s saving economy. Montanism, for Tertullian, was not the cause of this concern but its consequence.

In the end, Tertullian rejected borrowed authority and philosophical systems in favour of a faith built on its own foundation. Christ entrusted the gospel to fishermen, not sophists, and Tertullian embraced that inheritance. Faced with verbal excess and speculative confusion, he applied a single criterion: truth is simple. God, once known, cannot be uncertain; salvation, once revealed, cannot be divided. What appears plain is, in fact, complete. ("Tertullian, First Theologian of the West" by Eric Osborn)

Tertullian and the Case for Toleration

With the stark formulation

“Let one man worship God, another Jove” (Colat alius Deum, alius Iovem),

Tertullian articulated one of the earliest Christian pleas for religious toleration. Writing in the late second century, when Christians still faced legal insecurity and periodic persecution, he joined other Christian apologists in arguing that tolerance posed no threat to Roman order. On the contrary, it could be justified through principles of reason that Romans themselves claimed to value.

Early Christian appeals for toleration sit uneasily beside the later reality of Christian intolerance once the Church gained power in the fourth century. Christianity moved from a religio illicita seeking legal recognition to an established religion unwilling to extend the same tolerance to pagans or internal dissenters. This shift has often been explained as a moral failure brought about by power – a loss of early virtue rather than a theological problem.

Such explanations oversimplify a more complex development. An uneasy relationship with toleration was already present in Christianity’s formative centuries. While Christian intellectuals of the second and third centuries argued forcefully for tolerance, they struggled to accept its core premise: religious relativism. Toleration was defended as a practical necessity, not as a recognition of equal truth claims.

Tertullian offers a revealing case study of this tension. In works such as De idololatria, he explored how Christians might live within a pagan society while remaining uncompromisingly distinct. His arguments show how calls for toleration could coexist with rigid boundaries around Christian identity. Toleration, for Tertullian, did not require a rethinking of fundamental assumptions about truth, error, and false worship.

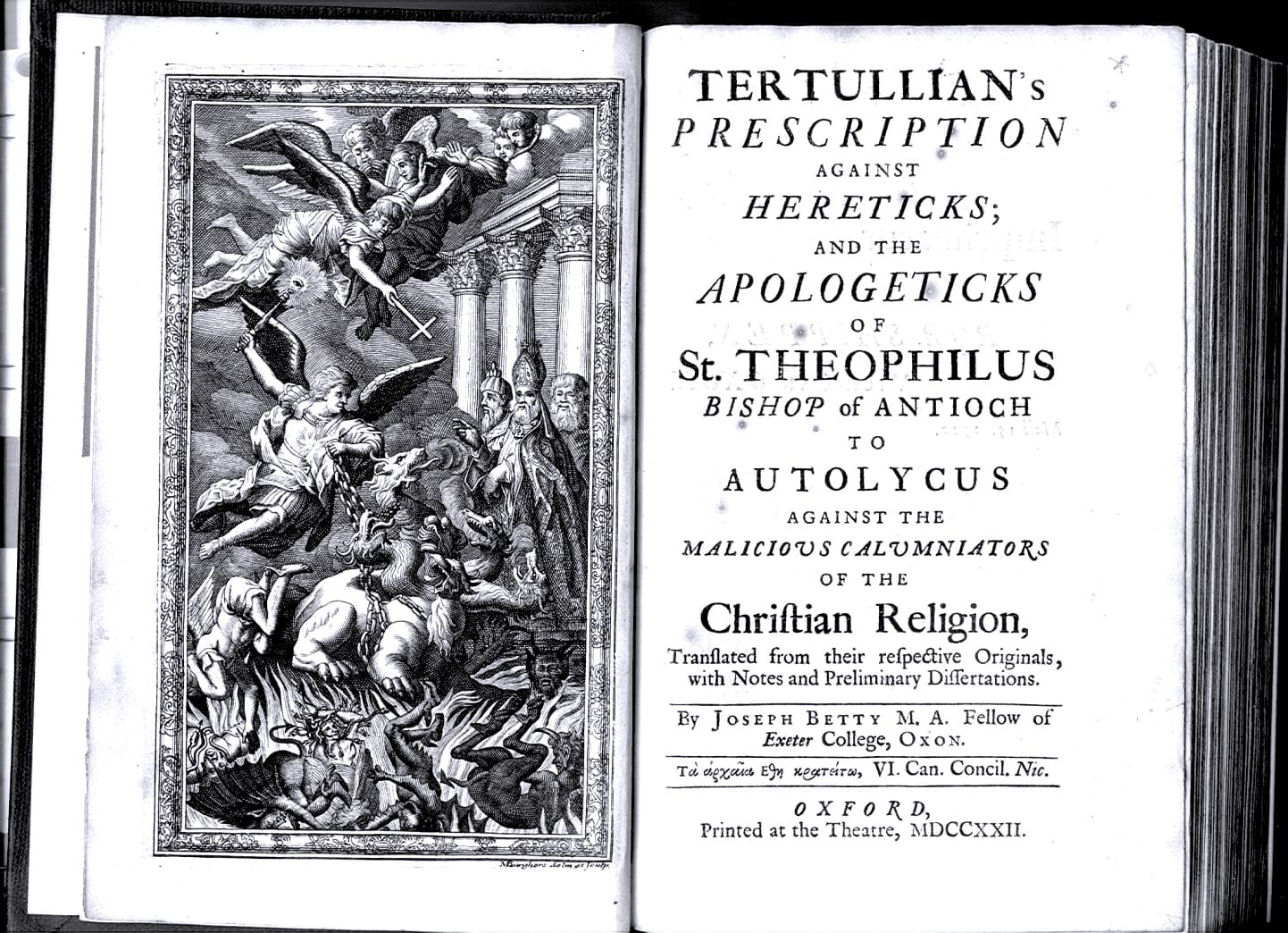

Polemic and the Limits of Tolerance

A fierce and gifted polemicist, Tertullian never treated tolerance as a central virtue. His writings are filled with sharp attacks not only against pagans and Jews, but also against fellow Christians whose theology diverged from his own, including figures such as Praxeas, Hermogenes, Marcion, and Valentinus. His work exposes how contradictory impulses – the demand for toleration and the rejection of doctrinal pluralism – could coexist within a single intellectual framework, shaping both Christian self-definition and its long-term historical consequences.

The Early Empire as a Religious Marketplace

Modern scholarship has described the religious world of the early Roman Empire as fundamentally pluralistic. John North has famously captured this transformation with the image of a “market-place of religions”, a setting in which a wide range of cults, practices, and beliefs competed across the Mediterranean. This open religious environment forms the social and intellectual backdrop to Tertullian’s thought. For perhaps the first time in antiquity, religious identity was no longer simply inherited as part of one’s civic or ethnic belonging, but could be actively chosen by individuals.

Choice, Conversion, and Christian Advantage

North emphasises that under the early Empire religion had become a matter of personal commitment rather than unquestioned tradition. In this competitive landscape, Christianity held a distinct advantage. More than any other religious group, Christians developed a language of conversion and articulated their faith as possessing a superior truth value.

This mode of religious argument, rooted in Jewish tradition, was initially foreign to pagan religion and only began to be adopted by non-Christian groups later, largely under Christian influence during the third and fourth centuries.

Tertullian’s plea for religious toleration must be read against this broader context. Writing in late second-century Roman Africa, he sought to persuade pagan elites that Christianity deserved a place within this crowded religious arena. Yet toleration, in such a setting, also meant rivalry.

Coexistence implied competition for allegiance, moral authority, and intellectual credibility. As a result, Tertullian’s appeals to tolerance are inseparable from sustained efforts to undermine the legitimacy of pagan religion on ethical, intellectual, and theological grounds.

This tension lies at the heart of Tertullian’s discourse. He appealed to the ruling authorities for acceptance while simultaneously challenging the religious foundations of their power. His ambivalence reflects a broader strategy developed by early Christian intellectuals: learning how to live as Christians within a pagan society without conceding the truth claims that defined Christian identity. In this way, Tertullian’s writings reveal not only an argument for toleration, but also the limits beyond which toleration could not go.

Idolatry as Absolute Incompatibility

For Tertullian, idolatry is not merely a mistaken or inferior form of religion. It is the gravest possible offence against God and represents a realm fundamentally opposed to true worship. Pagan religion is therefore not simply erroneous but illegitimate, both theologically and ethically. In De idololatria, written before his Montanist phase, Tertullian sets out to define idolatry precisely because this definition determines how Christians can live within a pagan world.

From the outset, he insists on an absolute incompatibility between the sphere of Christ and that of idols. One cannot serve both Christ and Caesar; the camps of light and darkness are mutually exclusive.

This opposition is expressed through stark imagery: Athens and Jerusalem share nothing in common, and allegiance to Christ excludes participation in the political and military structures of the Roman state. Military service, civic oaths, and ritual loyalty to the emperor all belong to the domain of idolatry.

Idolatry Beyond Images: Demons, Mediation, and Ubiquity

Tertullian’s understanding of idolatry goes far beyond temples and statues. Idols are not merely physical objects but anything that functions as an intermediary between humans and demons. Idolatry is therefore the worship of demons, even when it is not visibly recognisable as such. Pagan gods are exposed as daimones, and idolatry becomes a pervasive condition rather than a limited set of cultic acts.

Because idolatry is ubiquitous, it permeates daily life and cannot be avoided through spatial or ritual separation alone. All sin, whether overt or concealed, reflects idolatry in some form. This breadth makes vigilance essential: Christians must assume that idolatry can appear in ordinary social practices, professions, and moral compromises.

Daily Life Under Scrutiny: Professions, Practices, and Limits

The core of De idololatria is devoted to drawing practical boundaries for Christian life. Tertullian catalogues professions that must be avoided because they are directly linked to idolatry, including idol-making, astrology, teaching, and certain forms of trade. He then turns to indirect participation in pagan society, analysing social interactions, public events, and economic necessity.

Here, Tertullian develops a detailed moral casuistry, weighing principle against feasibility. The struggle against demons is not abstract or symbolic; it is concrete and ongoing, fought in workshops, marketplaces, festivals, and households. Roman greatness itself is reinterpreted as the product of irreligiosity, rooted in violence and war, which Tertullian treats as incompatible with true worship.

Cult, Truth, and the Expansion of Latreia

Underlying Tertullian’s rigor is a distinctive Christian understanding of latreia (worship). For him, worship is not confined to ritual acts but includes words, beliefs, and conduct. Christianity is defined by the proclamation of truth as much as by cultic practice. As a result, idolatry can occur wherever false affirmations about divinity are made, whether through speech, action, or accommodation.

This expansive conception sharply contrasts with rabbinic Judaism, where worship is more narrowly defined around temple sacrifice and prayer. Jewish idolatry remains largely tied to explicit pagan cult, allowing greater practical interaction with non-Jews. For Tertullian, by contrast, the breadth of Christian latreia leaves little room for tolerating alternative religious expressions.

Christianity, Judaism, and the Limits of Toleration

The comparison with Mishnah Avodah Zarah (highlights both parallels and divergences. While both traditions seek to regulate interaction with idolaters, Christianity’s broader definition of worship produces a stricter stance. Structural differences reinforce this contrast: Judaism remained a legally recognised religion, had largely ceased active proselytism, and possessed strong ethnic markers of identity. Christianity lacked these protections and markers, defining itself almost exclusively in religious terms.

More precisely:

- It is part of the Mishnah, the foundational compilation of Jewish oral law redacted around 200 CE.

- Avodah Zarah (literally “foreign worship”) addresses how Jews should live among idolaters without violating the prohibition against idolatry.

Because Christians shared language, dress, territory, and social space with pagans, identity could not be preserved through separation alone. Stricter moral boundaries became necessary to prevent assimilation. Tertullian’s severity reflects this vulnerability rather than simple polemical excess.

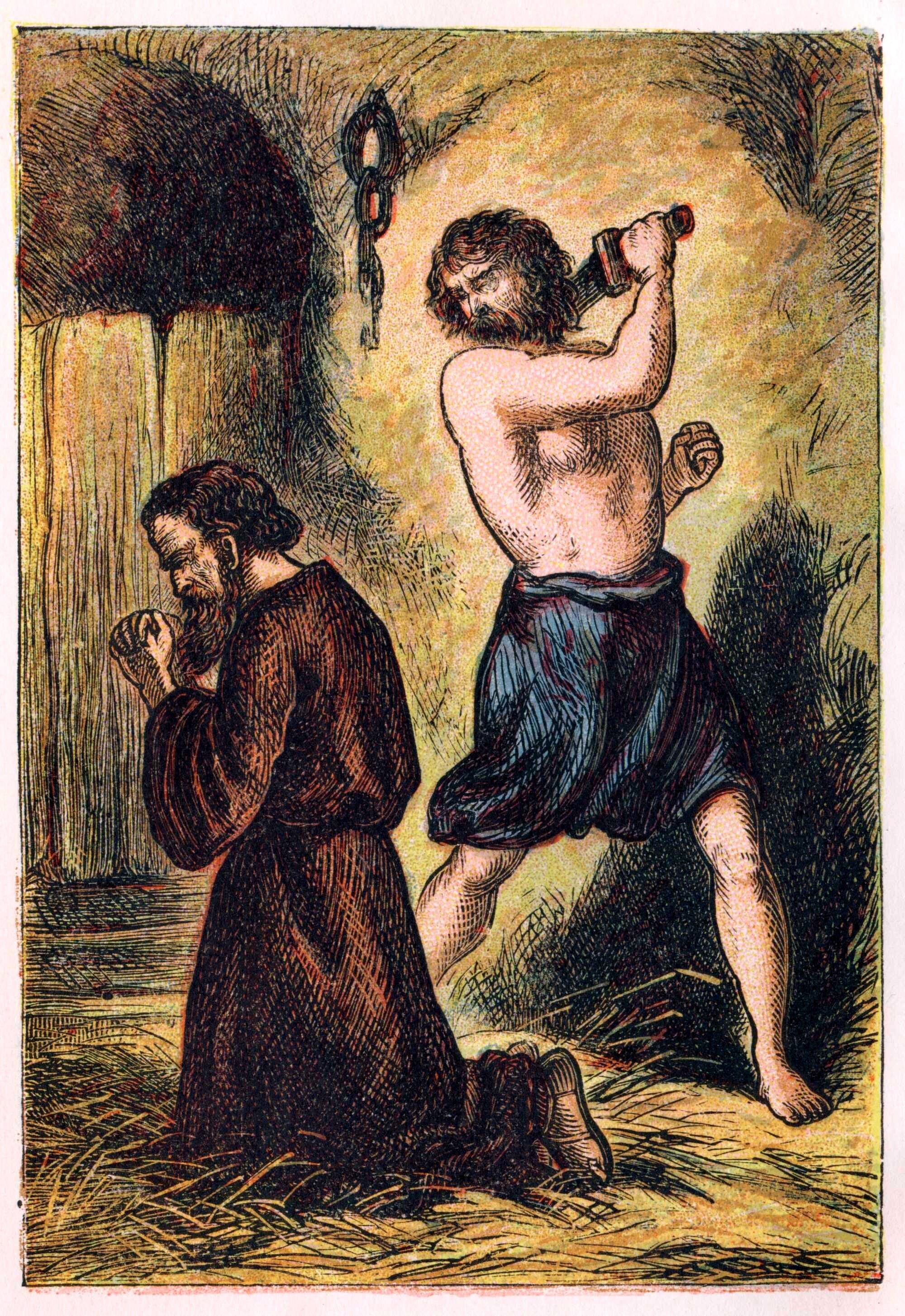

Intolerance as Virtue and the Ambivalence of Early Christianity

Tertullian’s rejection of religious toleration is not an aberration but part of a deeper ambivalence within early Christianity. While Christians demanded toleration for themselves, they often regarded intolerance as a sign of fidelity, even as a preparation for martyrdom. Readiness to suffer rather than compromise could be praised as a virtue.

This tension — between appeals for toleration and theological intolerance — helps explain why a robust concept of religious freedom failed to emerge in late antiquity. In Tertullian’s thought, the demand for truth ultimately outweighs the coexistence of competing religious claims. His work illuminates the intellectual conditions that later made the restriction of religious freedom not only possible, but justifiable, within Christian discourse. ("Tertullian on idolatry and the limits of tolerance" by Guy G. Stroumsa)

A Marketplace of Religions in the Early Empire

By the second and third centuries CE, religion in the Roman world was no longer a fixed inheritance tied automatically to birthplace or civic identity. Instead, the Mediterranean had become what John North famously described as a “marketplace of religions,” a space in which multiple cults, philosophies, and religious practices competed openly for adherents. (In such a marketplace, toleration was never neutral; it shaped who could compete and how.)

For the first time in antiquity, individuals could choose their religious affiliations rather than simply inherit them as part of their ethnic or civic identity. Religious identity thus became a matter of preference and commitment rather than tradition alone.

This pluralism formed the essential background to Tertullian’s apologetic project. Christianity did not emerge into a stable religious order but into a competitive environment in which novelty, persuasion, and legitimacy were constantly negotiated.

Conversion and the Redefinition of Religious Identity

Building on earlier insights, North argued that conversion represented a new and decisive category in religious history during the Hellenistic and early imperial periods. Religion was no longer merely something one practiced; it became something one consciously adopted. This shift altered the relationship between religion and identity in fundamental ways.

Christians benefited more than any other group from this transformation. Unlike most pagan traditions, Christianity articulated conversion as a necessary and meaningful act, framing religious change as a movement from error to truth. This discourse, inherited from Judaism, allowed Christians to present their faith as uniquely authoritative rather than simply one option among many.

Christian Advantage in a Plural Religious Landscape

Within this competitive environment, Christianity possessed several structural advantages. Most importantly, Christians claimed exclusive access to truth and framed their religion in universal terms. While pagan cults typically coexisted without asserting doctrinal superiority, Christian writers openly challenged the legitimacy of rival traditions.

Pagan religions lacked an established language of conversion and truth claims. Only under Christian influence, and relatively late—during the third and fourth centuries—did pagan intellectuals begin to develop comparable discourses. By then, however, Christianity had already gained a decisive foothold.

Tertullian and the Politics of Tolerance

Tertullian’s plea for religious tolerance must be understood within this competitive context. Writing in late second-century Roman Africa, he addressed a pagan audience that controlled political and legal power. His argument sought to secure Christianity a place within the religious “marketplace,” insisting that it should be permitted to exist alongside other cults.

At the same time, Tertullian fully understood that coexistence implied competition. His defense of tolerance therefore operated alongside a systematic effort to delegitimize pagan religion. Drawing on intellectual, ethical, and historical arguments, he attacked the coherence and credibility of Roman religious traditions while simultaneously appealing to Roman ideals of justice and legal fairness.

The Ambivalence of Early Christian Apologetics

This dual strategy produced a fundamental ambivalence in Tertullian’s discourse. On one hand, he argued for peaceful coexistence and legal recognition. On the other, he portrayed Christianity as the sole bearer of truth and depicted pagan religion as historically, morally, and intellectually flawed.

This tension reflects a broader challenge faced by early Christian intellectuals: how to live as Christians within a pagan society while asserting the superiority of their faith. Tertullian’s apologetic writings reveal not only a defense of Christianity but also an evolving strategy for negotiating identity, authority, and survival within a plural religious world. ("Christianity in the Roman Forum: Tertullian and the Apologetic Use of History" by Mark S. Burrows)

Tertullian never offered Rome reassurance. He exposed the cost of conviction in a world built on accommodation, and he refused to soften Christianity’s claim to truth for the sake of coexistence. His writings reveal why early Christianity could demand toleration while remaining deeply intolerant of rival beliefs. In doing so, he helps explain how a persecuted faith could later become a persecuting one — not through betrayal of its origins, but through tensions already present at the beginning.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: