Saint Helen: The Life of Helena Augusta, the Empress Who Changed History

Helena Augusta, also known as Saint Helena, was a significant figure in early Christian history and the mother of Emperor Constantine the Great, the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity.

Flavia Julia Helena, also known as Helena of Constantinople and revered in Christianity as Saint Helena, was an Augusta of the Roman Empire and the mother of Emperor Constantine the Great.

She was born into the lower classes, traditionally believed to be in the Greek city of Drepanon in Bithynia, Asia Minor, which was later renamed Helenopolis in her honor. However, there are several other proposed locations for her birthplace and origins.

Helena is famous for many reasons:

- Because she was the mother of Constantine,

- because she discovered the true cross,

- and because she founded many churches.

The origins of a legend

Based on information from Procopius, Helena's birthplace is commonly believed to be Drepanum—modern Hersek—in Bithynia, which Constantine later renamed Helenopolis in her honor. However, this is not the only city with that name. Sozomen mentions another Helenopolis in Palestina Secunda, though its exact location is unknown, and there is also a province called Helenopontus, allegedly named after Helena.

Another argument supporting Drepanum as Helena's birthplace comes from various Byzantine accounts of Constantine's life, which describe Constantius stopping at an inn in Drepanum during an embassy trip to Persia, where he had a liaison with the innkeeper's daughter, Helena—suggesting she might have been a prostitute working in a tavern. The next morning, Constantius gave her an embroidered purple robe.

Years later, when Constantius became Augustus, another embassy to Persia stayed at the same inn, where they found Helena and her son, Constantine, now about twelve years old. The envoys recognized the boy as Constantius' son due to the purple robe and his resemblance to his father. While intriguing, this story is legendary and cannot be used as a reliable historical source for identifying Drepanum as Helena's birthplace.

Even Procopius, our most credible source, is cautious about Drepanum, using the phrase "they say that Helena was born in this village," indicating uncertainty. Because of this ambiguity, Cyril Mango dismisses Drepanum as her birthplace, suggesting that the association with Drepanum may have arisen in Late Antiquity from the renaming of the city to Helenopolis, rather than from actual historical fact.

Just because Constantine named the place after Helena does not mean she was born there.

Emperor Constantine the Great, admiring a model city of Helenopolis. Illustration: Midjourney

Thus, there is no solid historical evidence confirming Drepanum as Helena's birthplace, placing it on the same speculative level as other locations like Trier, Colchester, and Edessa, mentioned in medieval legends. Consequently, her birthplace remains uncertain, though the fact that Helena had a Greek name (same as the legendary Helen of Troy) suggests she likely came from the eastern part of the empire.

The sources on Helena Augusta's life fall into three main categories, each highlighting different stages of her life.

- The first category includes texts that briefly mention Helena's early years, primarily in the context of documenting imperial history and Constantine's ascent to power, with some of these texts coming from a pagan perspective that was critical of Constantine.

- The second category involves artifacts such as inscriptions, sculptures, coins, and imperial monuments that depict Helena as a member of the imperial family. These contemporary sources require close examination of subtle changes in her depiction to understand Constantine's shifting views on his mother's role in his dynasty.

- The third category consists of Christian authors who offer more detailed, though often more legendary, accounts of Helena's religious activities in Palestine later in her life.

Interpreting these sources is complex. Objects and inscriptions from Helena's time are often disconnected from their original contexts, making analysis difficult. Textual sources also pose challenges, as the sequence of events described often doesn't align with the time of their composition, which usually occurred much later.

To navigate these issues, scholars can use a fourth type of evidence: natural and human geography, which includes information from ancient sources, material remains, current landscapes, and reconstructions of ancient travel. This spatial approach is essential because Helena's world and nature as a woman in the Roman Empire was marked by regional diversity, with imperial family members having various provincial backgrounds and experiences.

By comparing textual sources with regional and environmental contexts, scholars can reduce the impact of hindsight and improve the reliability of these sources.

Helena’s rise to power

Helena was not born into the elite. The earliest account of her origins, the Origo Constantini, written as early as the 340s, describes her as "very common" (vilissima), a term used in Roman legal texts to refer to lower-class individuals, known as humiliores. In the third century, this category included a large portion of the empire's population, both free and unfree.

With the granting of citizenship to all free residents of the Roman Empire in 212, class distinctions became more important than distinctions based on free, freed, or enslaved status. As a result, lower-class free individuals began to be legally viewed similarly to slaves. The term vilis, while ambiguous, could even suggest that Helena was born into slavery. There is some, albeit limited, evidence to support this possibility.

Helena's full name, at least later in her life, was Flavia Iulia Helena. She shared the family names Flavius and Iulius with Constantine's father, Constantius, which could imply that she was once his slave and took his names upon being freed, as was customary in the formal legal process of manumission, which also conferred citizenship.

However, names alone are not a definitive guide to social origin, especially during the third and early fourth centuries when Roman naming practices were changing. Names like Flavia and Iulia were very common by that time and had largely lost their original function as strict family names. Additionally, Helena's full name is primarily recorded after she was given the title Augusta by her son, and mostly appears on posthumous coinage.

Her full name might have been influenced by efforts from her son or grandsons to associate her more closely with the Constantinian imperial line after she became a public figure. Regardless, of her three names, Helena was likely the only one she carried throughout her life, indicating that it was given to her by her parents.

Helena was a popular name throughout the Roman world, though it was rarely used among the aristocracy before Constantine's reign, further suggesting that her origins were as common as the Origo Constantini suggests.

Helena's widespread name does not provide clues about her regional background. However, it is reasonable to assume she was born in one of the provincial settlements along the military highways on the northeastern edges of the Roman Empire. Several possible locations for her birthplace lie within this broad area between the Balkans and Mesopotamia, as previously mentioned.

In 324, Constantine gave his mother, Helena, the title of Augusta, a distinction that had been awarded to forty-two other imperial women before her. However, Helena stood out from the other famous women of the Roman Empire. Unlike previous recipients, who were either married to emperors or came from aristocratic families, Helena had neither been an emperor’s wife nor did she come from the aristocracy; her background was provincial and somewhat unclear.

Constantine’s decision to elevate her to a prominent role in his court was unprecedented and was motivated by both dynastic concerns and his religious agenda. After his victory over the pagan co-emperor Licinius, Constantine sent Helena to the Eastern provinces to symbolize the Christian nature of his rule.

Helena's growing prominence in Constantine's court, her elevation to Augusta, and her later travels in the Eastern provinces were all tied to dynastic crises and Constantine's efforts to strengthen his hold on power. As Constantine integrated other imperial households into his own, Helena, who was initially overshadowed by her daughter-in-law Fausta, eventually became the leading woman in the Christian empire, with significant influence.

Helena's life reflects an extraordinary journey from humble origins to a position of power within the empire.

St. Helen’s dream vision of finding the Holy Cross. Illustration: Midjourney

Her experiences, from living in remote settlements to imperial palaces, traveling extensively, and managing family conflicts, illustrate both the opportunities and limitations faced by women in the early fourth century. Helena’s unique role and experiences offer valuable insights into Constantine’s rule and the changing status of women during this time. (Helena Augusta: Mother of the Empire, by Julia Hillner)

Helena and the True Cross

As Jan Willem Drijvers writes in his book “Helena Augusta”, Helena is remembered for two main reasons.

- First, as we know, because she was the mother of Constantine the Great, the first Christian Roman emperor (306-337), who initiated the Christianization of the Roman Empire, eventually leading to a Christian Europe, and the foundation of the Byzantine Empire. Her involvement in Constantine's Christianization efforts secured her lasting fame.

- Second, Helena became renowned through the popular legend of her discovery of the True Cross. According to this legend, Helena traveled to Jerusalem, found three crosses, and identified one as the Cross of Christ. This story, which emerged about fifty years after her death, is considered historical fiction. However, during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, the legend was widely accepted as historical fact, making Helena a highly popular figure.

When a historical figure becomes central to a legend, fact and fiction often become intertwined, as happened with Helena. Many people, even into modern times, believed that Helena truly discovered the Cross of Christ, particularly because the story was given credibility by its inclusion in the fifth-century Historiae Ecclesiasticae. Edward Gibbon (an English essayist, historian, and politician. who's most important work, is The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire), was among the first historians to view the story of Helena finding the Cross as fictional, due to the lack of mention in contemporary sources like Eusebius and the Bordeaux pilgrim.

Despite Gibbon's accurate assessment, many have found it difficult to dismiss the legend as unreliable. Clergymen, in particular, often failed to distinguish between historical facts and legendary material, a lapse that might be understandable given Helena's sainthood.

However, professional historians are expected to clearly separate fact from fiction, though this expectation is not always met. For instance, a well-known ancient historian's book on Constantine, first published in 1969 and reprinted in 1987, includes a passage on Helena where fact and fiction are presented as equally credible.

This passage includes legendary elements, such as Helena being guided by a dream to find the Holy Sepulcher and discovering the True Cross, which have no historical basis, while the rest of the information, derived from Eusebius, is more likely to be historically accurate.

The modern historical portrayal of Helena is still muddled by the legend. More is known about her later years, including her position at Constantine's court and her relationship with Christianity. The most significant event in her life, as far as we know, was her pilgrimage, described by Eusebius, which later led to her being credited with the discovery of the True Cross.

The available sources for reconstructing Helena's life are limited. Aside from inscriptions, there are no contemporary written accounts, which means we must rely on sources written after her death, sometimes long after.

The most significant source is Eusebius's Vita Constantini (VC), a biography of Constantine written shortly after his death in 337, about ten years after Helena had passed. Eusebius dedicates a few paragraphs in Book III to Helena's journey to the eastern provinces, particularly her stay in Palestine.

Unfortunately, Eusebius provides no details about Helena's life before this journey, possibly because it either did not interest him or he lacked information about her earlier activities in the western part of the empire, where Helena likely spent most of her life. Notably, Eusebius does not mention her in the final edition of his Historia Ecclesiastica, probably completed around 324, despite including important updates about Constantine's reign.

Eusebius had specific reasons to discuss Helena's journey and stay in Palestine. As the metropolitan bishop of Palestine, he likely accompanied her during her travels in his region. Helena was a significant figure in the Roman Empire, deserving attention.

Most importantly, Eusebius focused on Helena's contributions to the Church and Christianity during her time in Palestine. His primary interest was not in personal lives but in individuals' relationships with Christianity, which is why Helena was important to him—she supported Christian communities and the Church.

Eusebius' VC generally reflects this approach, portraying Constantine's life as that of a protector and supporter of Christianity. Consequently, events or actions not relevant to Christianity or that might discredit Constantine as a Christian emperor were omitted. Eusebius did not aim to write a historical biography of Constantine, but to highlight his special role in the progress of Christian providence.

Because of this one-sided and favorable portrayal, Vita Constantini has been criticized, especially by 19th-century historian Jacob Burckhardt, who accused Eusebius of distorting history. However, the VC should not be dismissed as unreliable or useless; knowing Eusebius's intentions allows it to be used as a source with appropriate caution.

Eusebius' approach to historiography, emphasizing a Christian perspective, influenced all subsequent Christian authors.

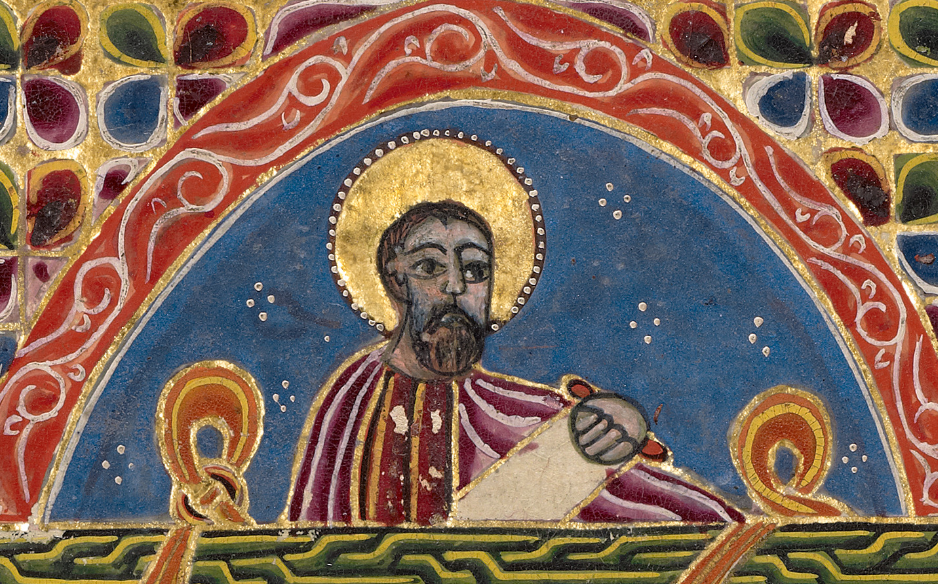

Icon of Eusebius of Caesarea as a Saint in Medieval Armenian Manuscript from Isfahan, Persia. Public domain

As a result, Christian sources, including the fifth-century Church Histories, offer limited historical information about Helena's life but are rich in legendary material.

Nevertheless, these sources still provide useful information for reconstructing her life. Additional details can be found in the works of minor Roman historians like Aurelius Victor, Eutropius, and Zosimus, as well as other historical sources such as various Chronicles and the Liber Pontificalis.

Beyond written sources, inscriptions, coins, and archaeological remains offer insights that help form a picture of Helena's life. Ultimately, Helena is more famous for the legend that credits her with discovering the cross on which Christ was crucified than for the details of her actual life.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: