A Well Full of War: Skeletons in Croatia May Be Victims of Rome’s Forgotten Battle

A decade-old excavation in Osijek, Croatia, revealed seven intact skeletons in a Roman well. A paper just published in PLOS ONE re-examines the find and argues they were likely soldiers from a third-century clash near Mursa.

A peer-reviewed study published very recently (October 15, 2025) takes a fresh look at a stark discovery in Osijek, Croatia—the Roman city of Mursa. In 2011, excavators cleared an old water well and found seven complete human skeletons at the bottom.

The new paper pulls together dating, diet clues, and genetic data and reaches a careful conclusion: these men were almost certainly Roman soldiers who died during the Crisis of the Third Century, most likely in the battle of Mursa (260 CE). The well, once used for drinking water, became a one-time grave on a very bad day for the city.

The find: a well that turned into a grave

The bones lay fully articulated, with arms and legs still in place. That detail matters. When a body is moved long after death, joints loosen and parts separate. Here, the positions show the men were thrown in soon after they died, in a single operation.

There were no coffins and no grave goods—not even the usual tokens that appear in formal burials. The well shaft itself sat inside the ancient city plan, close enough to everyday life that leaving bodies in it would have been both a health risk and a reminder of violence. Sealing it quickly would have restored a measure of normality and kept the city moving.

The scene fits emergencies recorded elsewhere in the Roman world. When disease, siege, or fighting hit a town, people sometimes used deep, ready-made holes—cisterns and wells—to get bodies out of sight and out of the way.

In Osijek, the well fill reads as a single event, not a place used again and again. That suggests a cleanup after fighting, not a long crisis with repeated deposits. It is the sort of hurried solution you would expect in a city that needed to be safe by morning.

Pinning down the date: a coin and a clock inside the bones

The study’s timeline rests on two simple ideas:

- First, the team dated four of the skeletons by radiocarbon, which is a natural clock inside organic material. All four measurements point to the second half of the third century CE, clustering tightly in the decades when the empire’s Danube frontier shook.

- Second, the excavators found a Roman coin in the same well fill. It is a sestertius minted in 251 CE. A single coin never dates a burial on its own—coins travel, and people save them—but when you place it beside the radiocarbon window and the one-event backfill, it becomes a strong anchor.

Together, they say: these men died after 251 CE, and likely not long after, because the well was sealed in one go. For a city like Mursa, which sat on a key river route and army road, that points straight at the year when a usurper named Ingenuus challenged Emperor Gallienus near the city—260 CE.

Why Mursa? The injuries and the setting tell the same story

All seven individuals were adult males—the age range you would expect for soldiers. Several show healed injuries from earlier blows, the long-term wear of hard service in their joints and spines, and dental and bone changes that track with repeated physical strain.

More importantly, two carry sharp-force cuts and puncture wounds with no healing, the sort of damage that happens in close-quarters fighting and leads to immediate death. Others show blunt-force trauma to the skull, consistent with face-to-face hits in a melee.

Clues from food and background line up. Chemical “signatures” in the bones—stable isotopes—reflect what people ate. Here they point to a grain-heavy diet with only modest animal protein and almost no seafood, a pattern that makes sense for men rotating through inland garrisons.

The DNA is a final nudge. These seven do not form a local family group; instead, they show a mix of backgrounds you would expect in a Roman unit that drew recruits from different regions of the empire. Add those lines together—adult males, battle-type injuries, grain diets, mixed origins—and the profile looks military.

The place matters as much as the bodies. Mursa was a crossroads city on river and road, strengthened in the second and early third centuries and badly exposed when the empire fractured. In 260 CE, as sources record, Gallienus faced Ingenuus near Mursa.

The aftermath described in the new study—one rapid deposit, equipment presumably removed, water supply restored—fits what a city would do after fighting at the gate. The research stop short of absolute proof, but its language—“most probably the battle of Mursa from 260 CE”—reflects how many clues point the same way.

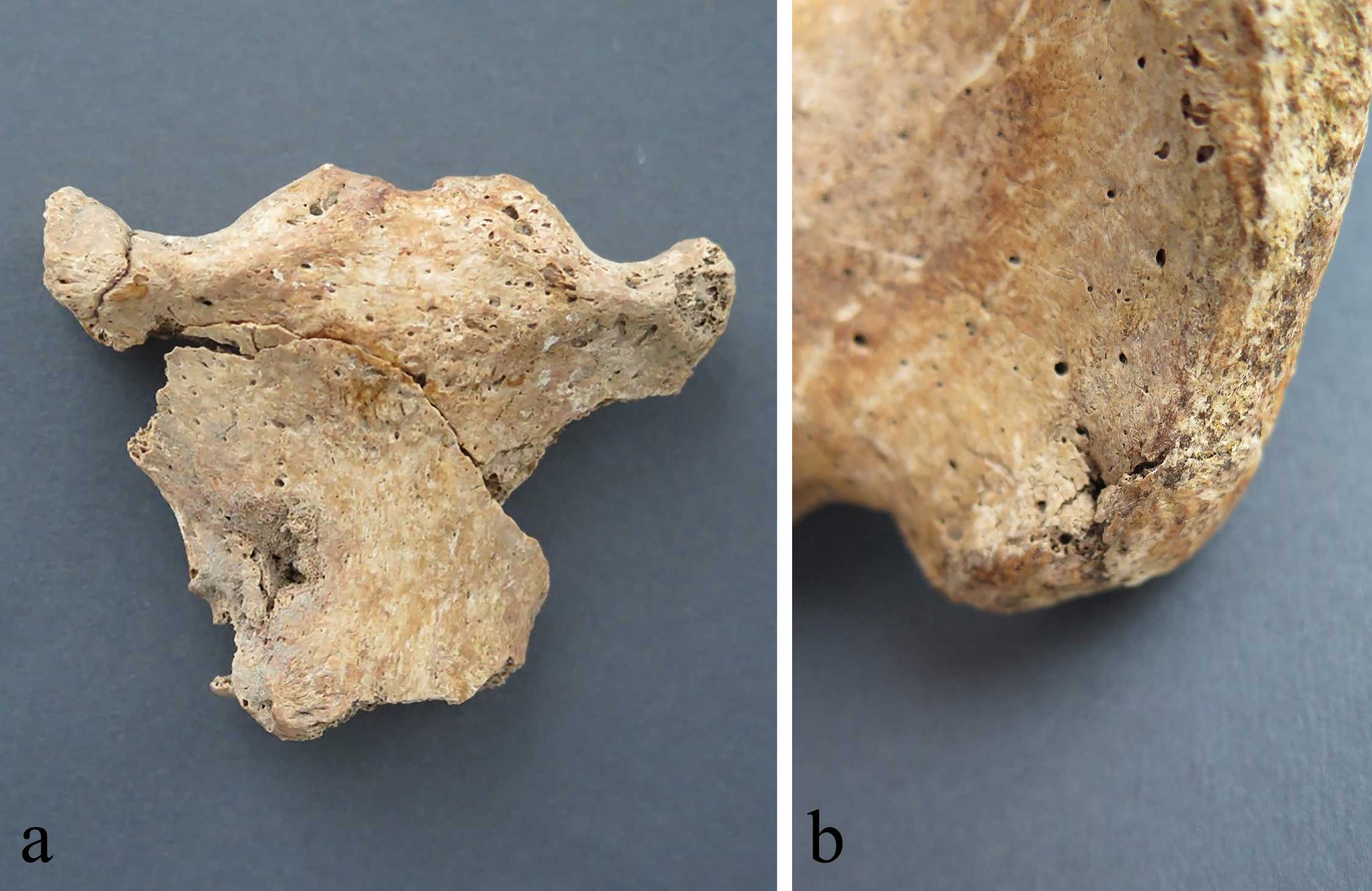

Roman skeleton bone fragments. Credits: Mario Novak, Orhan Efe Yavuz, Mario Carić, Slavica Filipović, Cosimo Posth

Image #2: Puncture wound on the anterior side of the manubrium, puncture wound on the posterior side of the right ilium

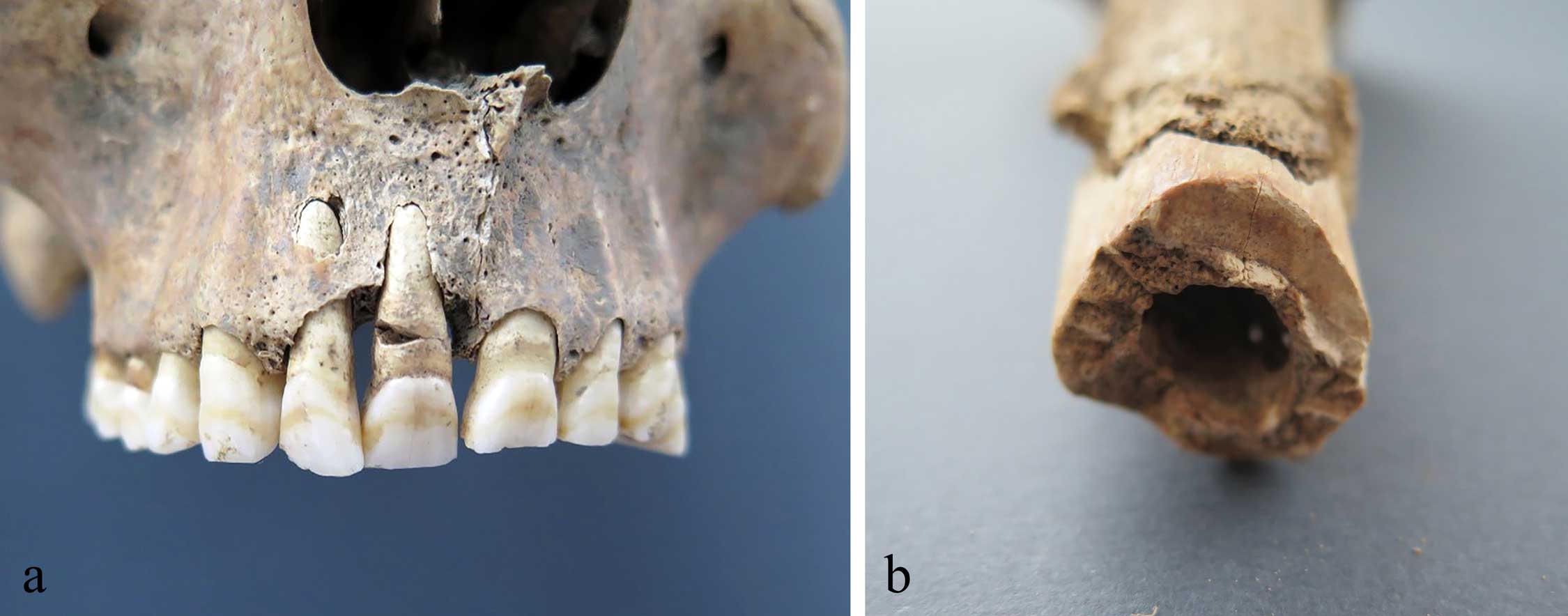

Image #3: Broken maxillary central right incisor, cut to the diaphysis of the left humerus

What the well tells us now

The Crisis of the Third Century can feel abstract: a list of emperors and usurpers sliding past one another in hurried succession. Finds like this one give that crisis a street address.

They show how a city coped when chaos arrived: a fast cleanup, a sealed well, and a return to order as soon as possible. They also remind us that Rome’s armies were built from many places. The seven men in Osijek were not local cousins; they were strangers brought together by service, carrying old scars into a final fight.

The study is also a case in how science can tighten a story without claiming more than the evidence allows. Radiocarbon explains the “when” in simple numbers. Isotopes give a rough “what they ate,” which helps place them. DNA answers “who they were like,” at least in broad strokes.

None of those tools gives a name. Together, they point to the most likely scene: soldiers killed in or right after the battle of Mursa (260 CE), cleared quickly and lowered into a well so the living could drink, repair, and move on. That restraint—arguing “likely” rather than shouting “certain”—is part of what makes the paper convincing.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: