A Day in the Life of Ancient Rome: From Dawn Till Dusk

How was the daily life of the simple and not so simple people in Ancient Rome?

The ancient city of Rome, with its grandiose monuments, bustling forums, and intricate social rituals, offers a fascinating glimpse into daily life over two millennia ago. Historians have been able to describe how the Roman Empire citizens spent their waking hours, from the first light of dawn to the quiet of night, revealing a day filled with activity, leisure, and social intricacies.

The Start of a Roman Day - The Salutatio

A typical Roman day commenced with the sunrise to maximize the use of daylight.

Every morning, upon waking, a young child would adorn themselves with a protective amulet: a bulla for boys, resembling a locket, or a lunula for girls, shaped like a crescent moon. A common design for these amulets was the phallus, a motif borrowed from ancient Greek culture, thought to safeguard the wearer from danger or malevolent forces. These pendants were either worn around the neck or carried in a tiny leather pouch.

The morning marked the day's most hectic period, with household members bustling about, especially the kitchen staff, despite breakfast being a relatively minor affair in Roman times. In the homes of the affluent, benches were arranged outside for clients to sit while waiting for their audience with the head of the household. Entry into the house was universally through the front door, where visitors might tread on well-maintained floors or, in older residences, a combination of intact and broken paving, yet wealthier homes consistently offered a sense of spaciousness.

The women of the house, went to the market in the morning, after securing their jewelry. They might also leave accompanied by a slave or be transported in a 'litter' (in Ancient Rome, a type of portable bed known as a lectica, or "sella," was frequently used to transport members of the imperial family, dignitaries, and the wealthy elite, especially when they were not travelling by horse). During her daytime outings, they wouldn't encounter wheeled traffic in the streets, as such vehicles were prohibited until nighttime.

The first meal, ientaculum, usually included cheese, fruit, and possibly leftovers, with bread being a staple part of the diet. The morning hours up to noon were dedicated to social visits by clients to their patrons. In this ritual known as salutatio, individuals from lower social standings would visit a higher-status patron (patronus) in his home to offer their respects, seek favors, and in return, possibly receive food or money (sportula) in a basket.

These exchanges occurred in the patron's atrium, with both parties wearing togas for the formal interaction. The patron-client relationship was deeply rooted in the social and economic standings of the involved parties, where a man could be both a patron to some and a client to others of higher rank. Clients seeking their patron's favor were often seen accompanying him in public, enhancing his prestige and visibly demonstrating his influence and status.

In contrast to the contemporary method of using watches and clocks for timekeeping, the Romans lacked instruments to precisely segment a full day (our 24-hour cycle) into smaller intervals. Their approach involved monitoring the sun's position throughout the day, utilizing a sundial to split the daylight period into twelve equal segments known as horae (hours). Consequently, the duration of a Roman hour varied, being shorter in winter and longer in summer due to the seasonal changes in daylight length. The day was anchored around three key moments: sunrise, noon, and sunset, with any further division of time occurring within these intervals. Similarly, the nighttime was divided into twelve equal portions.

To Work and Leisure: The Roman Midday

Workdays in ancient Rome began at dawn and concluded around noon. The school day, as did all work, started before sunrise.

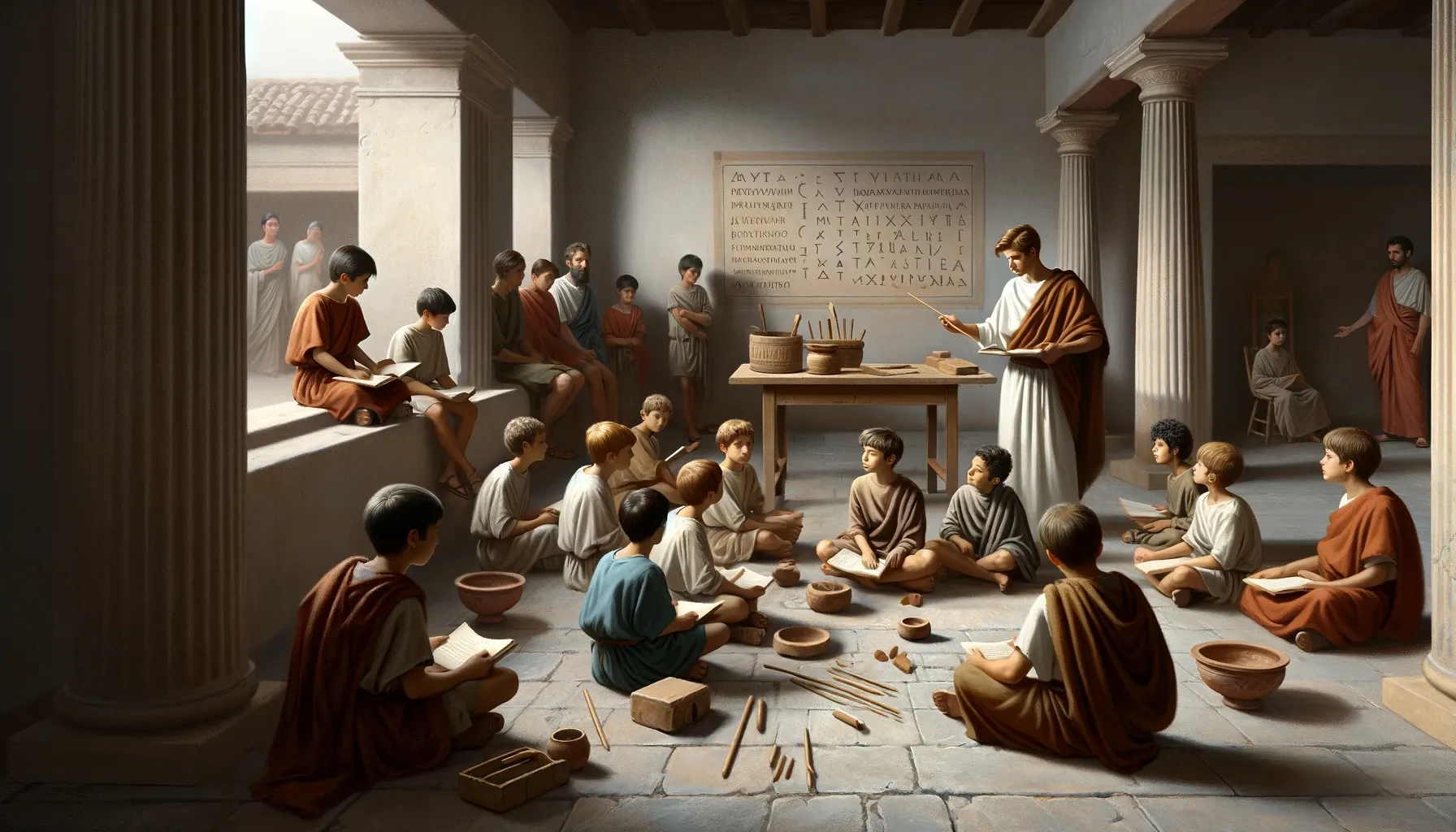

Initially, Roman education was conducted at home, with fathers, if literate, teaching their sons to read and write, alongside lessons in Roman law, history, customs, and physical training for military preparedness. The core values instilled included reverence for the gods, respect for law, obedience to authority, and honesty. Daughters received their education from their mothers, learning domestic skills such as spinning, weaving, and sewing.

By around 200 BC, the Romans began to incorporate elements of the Greek educational system, though without significantly expanding the curriculum. They started sending their children, including boys and, with paternal consent, some girls, to external schools from the age of 6 or 7.

These young learners were taught to read, write, and perform basic arithmetic. They utilized scrolls and books for reading, wax-coated boards for writing, and pebbles for solving mathematical problems. Their education included learning Roman numerals and memorizing and reciting lessons. By the age of 12 or 13, boys from the upper classes moved on to "grammar" school to study Latin, Greek, grammar, and literature. At 16, some pursued further education in rhetoric to become skilled orators.

Education for children from less affluent backgrounds was not as accessible. Schooling required payment, and the notion of large classes in dedicated school buildings was not a reality. Instead, education outside the home typically meant small group instruction at a tutor's house. In-home education was often provided by educated slaves. However, in poorer households without slaves, parents themselves took on the role of educators, as was the practice in earlier Roman times.

In the afternoon, children were released from the rigors of their school day, preoccupied with two main desires: to play or to eat. Upon arriving home, they would make a beeline for the kitchen, beseeching the cook for food. If not seeking a snack, they would dash off to the garden to engage in play.

Around the fifth hour, Romans had their prandium, (lunchtime) which was around noon. This meal was light, akin to a snack, and often consumed quickly or on the move. Residents of the city might choose to eat lunch at home or opt for a meal from a tavern or street vendor. They could also visit a thermopolium or popina, establishments that served a similar purpose to modern fast-food restaurants. These eateries became particularly widespread near public baths during the Empire era, reflecting the Romans' increased access to a diverse range of goods and their enhanced leisure time compared to the earlier Republican period.

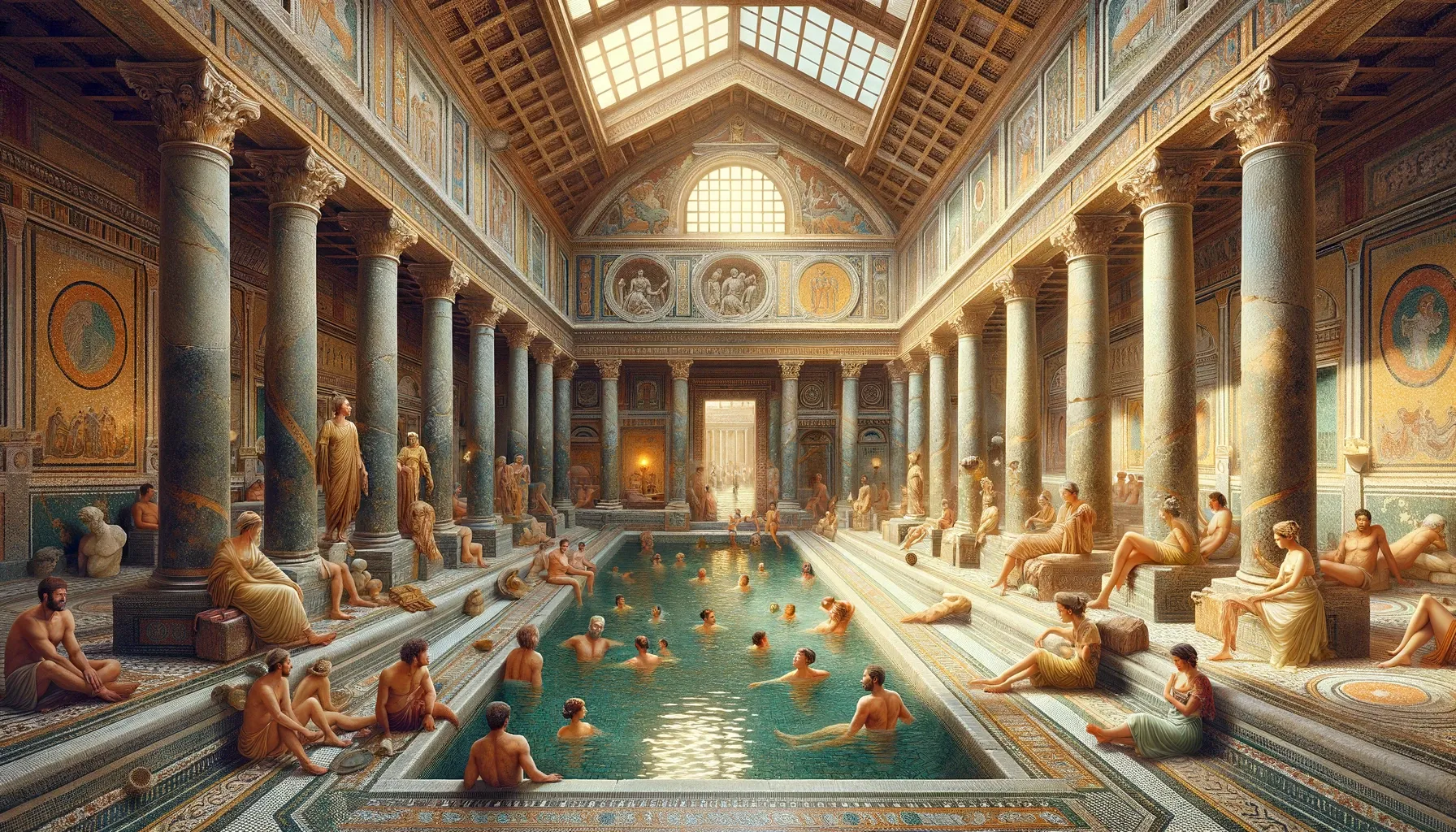

The Roman schedule allowed citizens to dedicate their afternoons to leisure and personal pursuits. The city offered a plethora of entertainment options, from theatrical performances and chariot races to the infamous gladiatorial contests of the Colosseum. On days devoid of public spectacles, Romans might engage in gambling, exercise, or enjoy the communal atmosphere of the thermae, the grand bathhouses that were a cornerstone of Roman social life.

The thermae were not merely places for bathing but complex leisure centers featuring gardens, exercise areas, and spaces for intellectual discussion. They epitomized the Roman commitment to otium, leisure time devoted to activities that nurtured the mind and body. The cost of entry was nominal, ensuring that these spaces were accessible to a broad swath of society, from the wealthiest patricians to the common plebeians.

Evening Repast: Supper in the Roman Household

As the day waned and the baths emptied, Romans turned their thoughts to cena. This principal meal, was served in the late afternoon or at the beginning of the evening. The dinner menu varied significantly based on one's economic status and the occasion's formality. Those with limited means might consume modest fare, including vegetables, fruits, grain-based soups, possibly some meat, and invariably bread. Given its high cost, meat wasn't commonly the centerpiece of meals for the average person. The less affluent relied heavily on grains, which were either baked into bread or cooked into a type of porridge known as puls. While drinking water was accessible, diluted wine was the beverage of choice, or in poorer households, water mixed with vinegar.

Unlike the simple morning repast, supper was an elaborate affair, particularly for the wealthy. Dining rooms were furnished with reclining couches surrounding tables laden with diverse and often exotic dishes. Guests were entertained with food, wine, and conversation in an atmosphere that reflected the host's social status and cultural sophistication.

The cuisine of ancient Rome was varied and sophisticated, featuring ingredients from across the empire. Suppers could extend over several hours, with courses ranging from appetizers to desserts, accompanied by an array of wines. The most sumptuous banquets, often hosted by emperors, could last until the early hours of the morning, showcasing the empire's culinary wealth.

Nightfall: The City Quiets

As night descended, the vibrant energy of Rome dimmed. The streets, lively and crowded during the day, became quiet and potentially perilous. Wealthy Romans, accompanied by torch-bearing slaves, navigated their way through the darkened city to the safety of their homes. Meanwhile, the less fortunate made do with the dim light of the moon or stars, wary of the dangers that lurked in the shadows.

The contrast between day and night in ancient Rome underscores the duality of public and private life. The daytime was marked by communal activities and public engagements, while the night belonged to the family and the household gods. This rhythm of life, dictated by natural light and societal norms, shaped the daily routines of Romans, from the highest senators to the humblest artisans.

Reflections on Roman Daily Life

The daily life of ancient Romans was a tapestry of work, leisure, and social obligations, set against the backdrop of the empire's grandeur and complexity. From the morning rush to the evening's leisurely pace, the routines of Romans reflect a society deeply invested in the values of community, tradition, and the pursuit of otium. As we explore the remnants of their world, we gain insights into a civilization that, in many ways, laid the foundations for our own.

In understanding the daily rhythms of ancient Rome, we are reminded of the universality of human experience, transcending time and geography. The echoes of Roman life, with its blend of the mundane and the extraordinary, continue to fascinate and inform, offering a window into a world both alien and strangely familiar.

This exploration into the daily life of ancient Romans reveals a civilization rich in tradition, social complexity, and a profound appreciation for the balance between work and leisure. As we peel back the layers of time, the ancient city of Rome emerges not just as a place of monumental history but as a vibrant, living community.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: