The Consuls in Ancient Rome: A Pillar of Republican Governance

The consul was one of the highest elected political offices in the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire.

CON'SUL (ὕπατος): The consul was the highest-ranking republican magistrate in Rome. The term likely derives from "con" and "sul," with "sul" sharing the same root as "salio." Thus, consules are those who "go together," similar to how "exul" means "one who goes out," and "praesul" means "one who goes before.

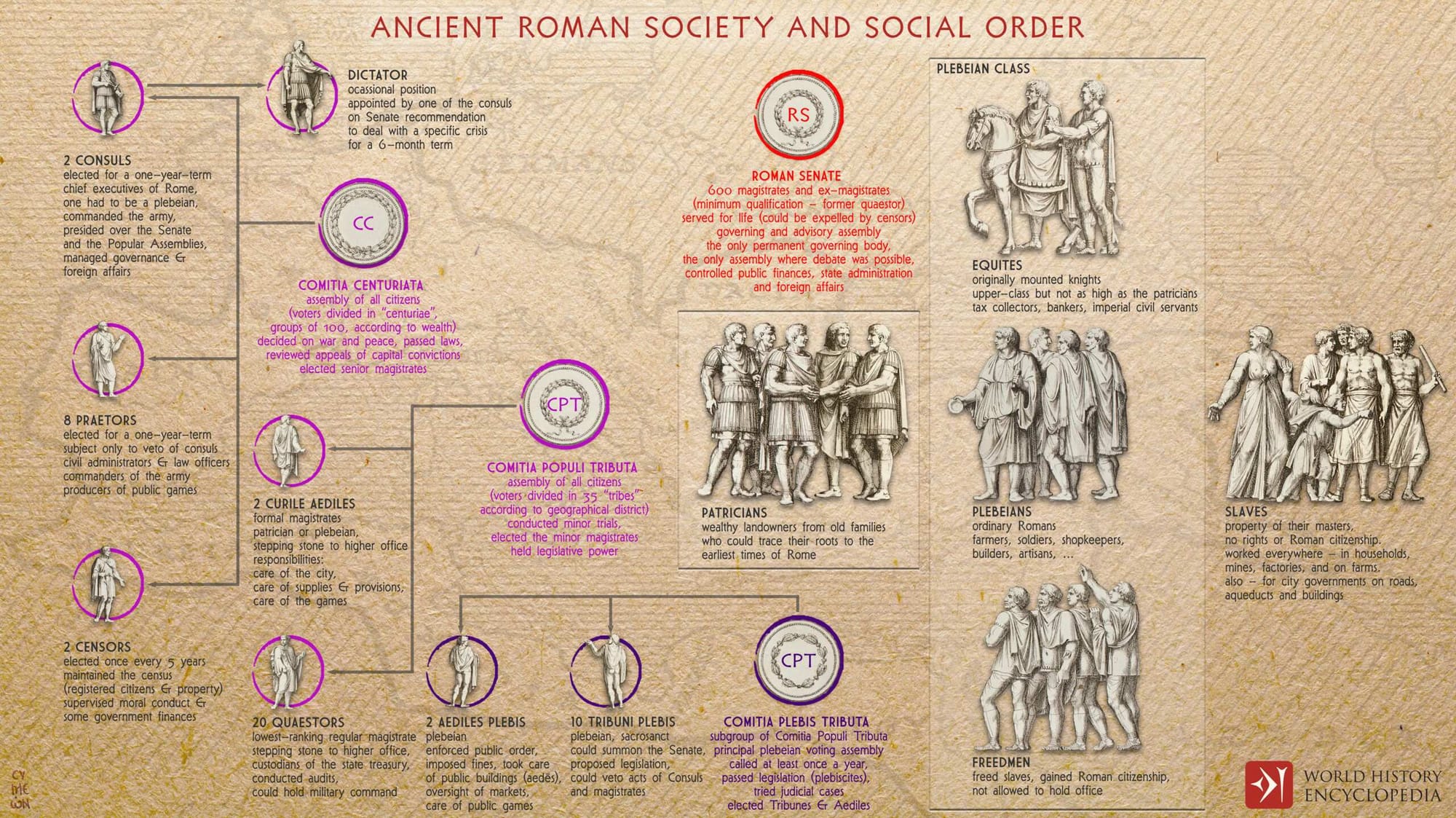

What the consuls really were, was acting as the chairmen of the Senate, which functioned as an advisory board. They also commanded the Roman army, each overseeing two legions, and held the highest judicial authority in the Roman Empire. Consequently, the Greek historian Polybius of Megalopolis compared the consuls to kings.

Their powers were limited only by laws, Senate decrees, or decisions from the People's assembly; their decisions could only be overridden by a veto from another consul or a tribune. This allowed consuls to intervene in the actions of praetors, aediles, and quaestors. However, tribunes, censors, and dictators were immune from consular interference.

A consul was accompanied by twelve bodyguards (lictores) and was permitted to wear a toga with a purple border. The Roman year was named after the two consuls in office.

What was the role of a consul in Ancient Rome?

There was a tradition that King Servius, after organizing the state constitution, intended to abolish the monarchy and replace it with the annual magistracy of the consulship. Regardless of the tradition's accuracy, it indicates a profound understanding of the Roman state and its institutions.

The immediate establishment of the consulship following the abolition of the monarchy suggests it was premeditated. The consulship was not a Latin institution, as in Latium, the monarchy was replaced by a temporary dictatorship with king-like powers.

The consulship, established as a republican office in Rome right after the end of the monarchy, demonstrated its republican nature by dividing power between two individuals (imperium duplex) and limiting their term to one year (annuum).

This principle was mostly upheld during the republican period, with exceptions such as the appointment of a dictator instead of two consuls, or one consul remaining in office alone if the other died, typically due to a short remaining term or religious reasons.

Normally, if a consul died or resigned, the other would convene the comitia to elect a successor (subrogare or sufficere collegam). However, in the republic's last century, there were deviations, like Cinna serving nearly a year as sole consul, Pompey being appointed sole consul to avoid a dictatorship, and Cinna and Marius seizing consulship power without elections.

In the earliest times, the chief magistrates were called praetores, highlighting their role as commanders of the army or as leaders of the state. This title is evident in ancient legal and ecclesiastical documents, as well as in terms like praetorium (the consul's tent) and porta praetoria in the Roman camp. Occasionally, they were also referred to as judices, although this was likely never their official title but rather a reference to their judicial role.

The title consules was introduced for the highest magistrates in 305 B.C. and remained the official designation until the fall of the Roman Empire. With the establishment of the republic and the banishment of Tarquin, all royal powers were transferred to the consuls, except for the role of high priest, which was assigned to a priestly official known as the Rex Sacrorum or Rex Sacrificulus.

The first Rex Sacrorum was appointed by the college of pontiffs at the command of the consuls and inaugurated by the augurs. This official was always elected and inaugurated in the comitia calata under the pontiffs' leadership, and the position was consistently held by a patrician. Because the Rex Sacrorum had no political influence, plebeians did not seek this office.

Over time, even the patricians seemed to regard the position as insignificant, sometimes leaving it vacant for one or two years. During the civil wars at the end of the republic, the office fell into disuse. However, Augustus revived it, and it remained in existence during the empire until it was likely abolished in the time of Theodosius. (Consul by Leonhard Schmitz, Ph.D., F.R.S.E., Rector of the High School of Edinburgh)

The most famous Roman Consuls

The full list of Roman Consuls might be too long, but there were prominent historical figures that served as consul of Rome, amongst their other duties as dictators, generals, philosophers, or even Emperors. These are the most famous of them:

- Julius Caesar: Renowned military general and statesman, consul in 59 BCE, later became dictator and pivotal figure in the transition from Republic to Empire.

- Cicero: Famous orator, philosopher, and politician, consul in 63 BCE, known for his efforts against the Catiline Conspiracy.

- Gaius Marius: Consul seven times between 107 BCE and 86 BCE, known for military reforms and victories against Germanic tribes.

- Lucius Cornelius Sulla: Consul in 88 BCE and 80 BCE, known for his dictatorship and extensive constitutional reforms.

- Pompey the Great: Consul in 70 BCE, 55 BCE, and 52 BCE, renowned military leader and political figure, rival of Julius Caesar.

- Mark Antony: Consul in 44 BCE, key player in the aftermath of Caesar’s assassination, and member of the Second Triumvirate.

- Augustus (Octavian): Consul multiple times, founder of the Roman Empire and its first emperor, transforming Rome from Republic to Empire.

- Tiberius: Consul in 13 BCE and 7 BCE, later became the second emperor of Rome.

- Scipio Africanus: Consul in 205 BCE and 194 BCE, celebrated for his victory over Hannibal in the Second Punic War.

- Marcus Claudius Marcellus: Consul five times between 222 BCE and 208 BCE, known for his military prowess during the Second Punic War and capturing Syracuse.

The consules designate and their power

During the first century B.C., consules designati held an elevated political status. The most evident sign of their prominence during this period was their privilege to speak first in Senate debates, even before sitting consuls and former consuls (consulars).

Mommsen (one of the greatest classicists of the 19th century), saw this privilege as partly an act of courtesy from current consuls towards their successors, but he also believed it had a political purpose: to limit the influence of leading senators who typically spoke first in debates. He traced this custom to the post-Sullan period, linking it to the change in the consular election date to July, possibly during Sulla's time.

Mommsen argued that this privilege did not exist earlier as it would have conflicted with the rights of the princeps senatus, an office that disappeared after the Sullan period. This right could also extend to praetors, allowing praetors-elect to speak before current praetors and senators of praetorian rank. A notable example is Caesar's speech on December 5, 63 B.C., during the Senate debate on the Catilinarian conspirators, where, according to Cicero, Caesar spoke "praetorio loco" as a praetor designatus.

Cicero's mention of the right of consules designati to speak first in Senate debates as part of the mos maiorum indicates that this custom must have been established long before his time. Determining the exact start of this tradition is challenging since all sources are from after the first century BC, and earlier references to consules designati are scarce.

Livy occasionally notes that the electoral process began at the end of the consular year ('in exitu anni', 'in exitu annus erat'), creating a brief interval between the election of the consuls and their assumption of office.

This procedure was initiated by the Senate, which would send a message to the presiding consul, instructing him to leave his province and return to Rome for the elections. Consequently, the election dates varied annually.

Livy provides specific dates for elections in the early second century: February 18 in 187 and 171, just before the Ides of March in 178, and January 26 in 169. These examples indicate that during this period, consules designati held their positions for a much shorter time, ranging from a few days to a few weeks, compared to the first century.

Before the first century BC, both consuls typically spent most of their term outside Rome, leading their armies in their assigned provinces. This was also true for most praetors. Consuls would only be in Rome for the first few weeks or months of their term to fulfill their religious duties (such as expiating prodigies and presiding over the Feriae Latinae) and diplomatic responsibilities.

In the second century, the presiding consul returned to Rome solely to oversee the elections, usually spending just a few days in the city before returning to his province. His colleague would only return at the end of his term, though he often continued in office as a promagistrate. Consequently, once the consuls left for their provinces, the highest magistrate present in Rome was the urban praetor.

The consul’s elevated authority

Speaking first in senatorial debates was a significant honor with deeper implications. A consul designatus would initiate the debate with his speech, setting the direction for the discussion. Caelius wrote to Cicero in 51, during Cicero's stay in Cilicia, expressing curiosity about what consul designatus L. Aemilius Lepidus Paullus might say when opening the next Senate session ('primum sententiam dicentem') in response to Pompey's declaration that the Senate's decisions must be observed.

The first speaker had to clearly present his political stance before the other senators, a responsibility that could not be avoided. Securing a favorable Senate vote for his proposal (sententia), which then became a senatus consultum, enhanced his reputation. Sources sometimes refer to this individual as princeps sententiae. The priority given to consules designati underscored the special auctoritas (authority) they enjoyed after being elected.

Their ability to maintain and build upon this auctoritas depended on their wisdom and political actions. In the year 69, the consules designati used this auctoritas to defend Verres against his accuser, Cicero, who was merely an aedile designate, making Cicero's eventual victory even more remarkable.

Throughout the Roman Republic's history, the number of consuls remained fixed at two, unlike other offices that saw an increase in holders, which heightened competition among the aristocracy.

Each year, two consuls were elected by the centuriate assembly (comitia centuriata), usually convened by a current consul or, in special cases, by a dictator, interrex, or an early Republic military tribune with consular power. Initially, plebeian consuls were scarce, but a Licinian plebiscite in 367 BCE required the election of at least one plebeian consul. This practice became regular by 342 BCE, and the first fully plebeian consulship occurred in 172 BCE.

The consulship was the highest annual magistracy, with the lex Villia Annalis in 180 BCE setting a minimum age of forty-two, a rule confirmed by Sulla in 81 BCE. Consuls could serve multiple terms, and after the 3rd century BCE, their imperium was often extended beyond their term, making them promagistrates (pro consule) governing provinces.

The consulship was the peak of a political career, unless followed by the censorship, and carried significant social prestige, used by elite families for self-representation.

Consuls operated under collegiality, with each having the power to veto (intercessio) the other's actions and those of lower magistrates. If a consul died in office, a suffect consul (consul suffectus) was elected to finish the term. Consuls were eponymous magistrates, marking the official Roman chronology.

The start date for consuls varied; there was no fixed date in the 5th and 4th centuries. From the 3rd century, consuls possibly began their term on the Kalends of May. By 217 BCE, the consular year started on the Ides of March, and in 153 BCE, it was changed to January 1st. (Consul, by Francisco Pina Polo)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: