Monte Testaccio: A Roman Hill Entirely Made Of Amphorae Fragments

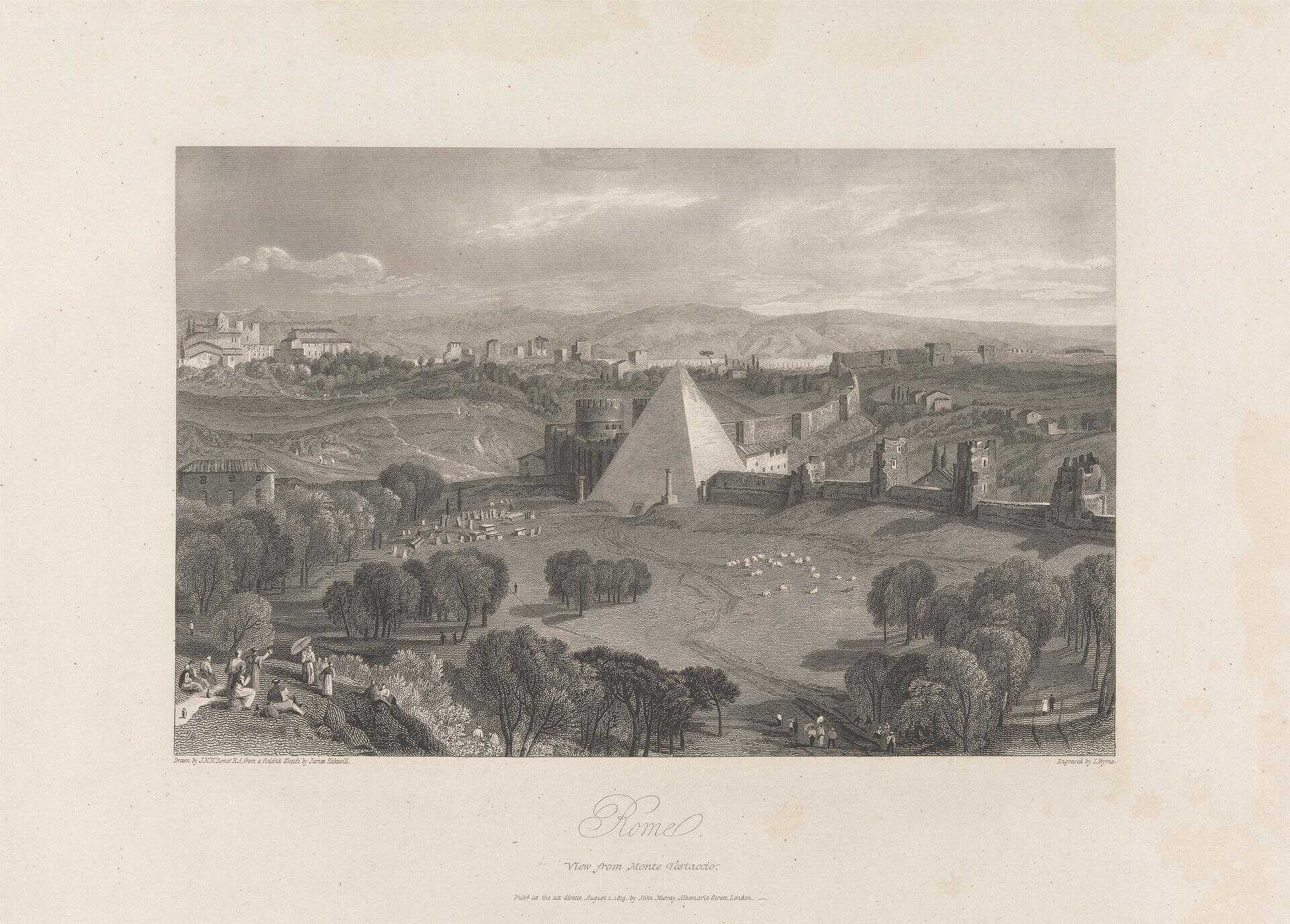

Monte Testaccio, is one of the most extraordinary archaeological sites in the city of Rome, totally artificial, composed of pieces of broken jars.

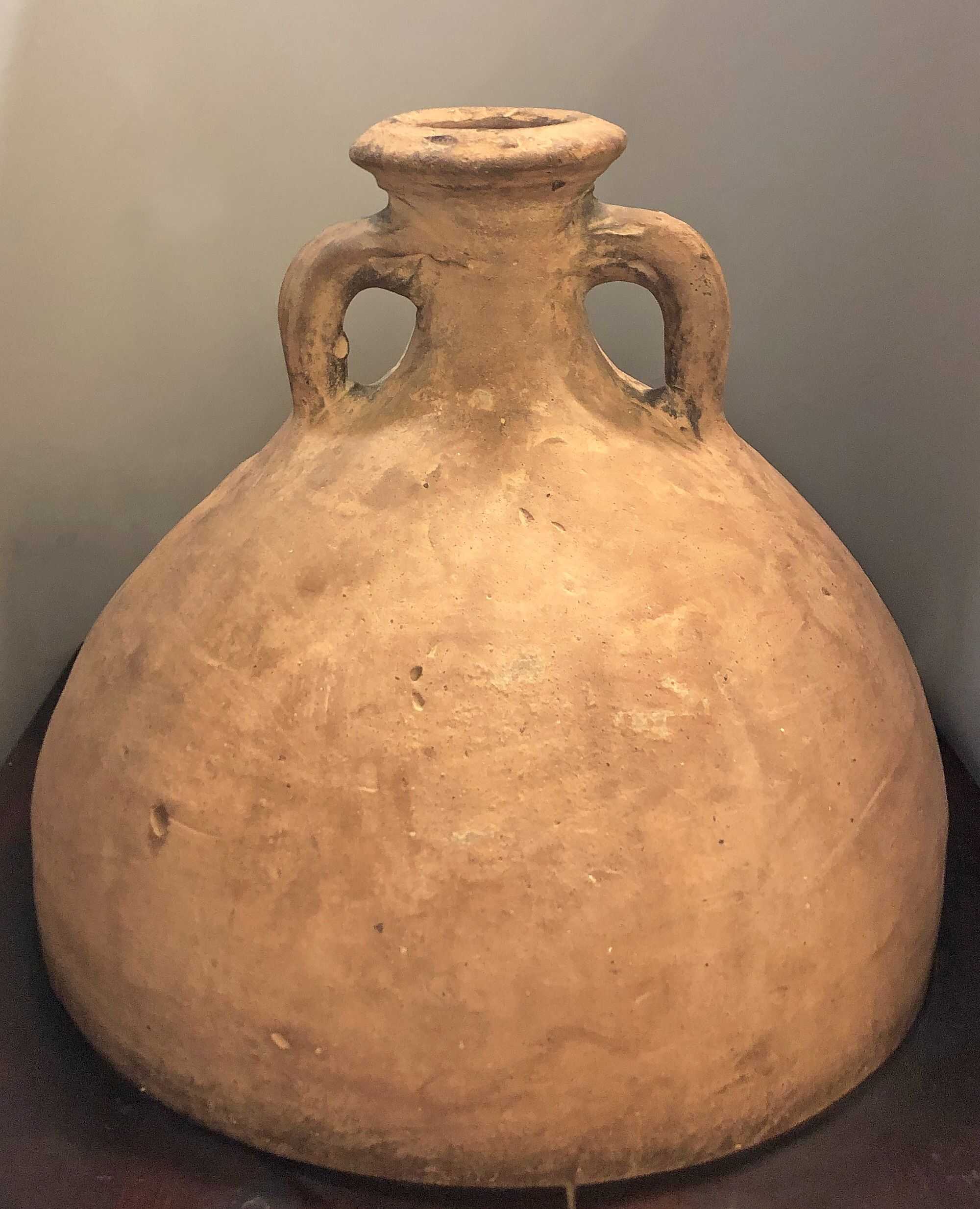

Also known as the "Mountain of Shards" or "Monte dei Cocci," Monte Testaccio is an artificial hill located in Rome, Italy. It’s one of the most unusual ancient Roman sites, made entirely of broken amphorae, which are terracotta vessels used to transport liquids like olive oil and wine in the Roman Empire.

The hill, which stands about 35 meters (115 feet) tall and covers around 20,000 square meters, is composed of an estimated astonishing number of 53 million amphorae fragments.

How to Get to Monte Testaccio

To reach the hill, located in the heart of Rome’s Testaccio neighborhood, you can take advantage of Rome's efficient public transportation system. From the city center, catch metro Line B to the Piramide station, and from there, it’s a short walk or bus ride to the site. Monte Testaccio is an archaeological area, and visits require reservations via the city’s cultural information service at +39 060608.

The hill itself is within the vibrant Testaccio district, known for its lively market and traditional Roman food. After visiting Monte Testaccio, you can explore the surrounding area, which includes dining options and restaurants that offer views of the ancient amphorae embedded into the hill’s walls. Be sure to make time for these local experiences while you’re in the area.

If you’re planning to explore more, Monte Testaccio also offers guided tours, where experts lead you through the archaeological findings and history of this remarkable site. For additional details, you can check Rome’s official cultural sites page.

The hill is an organized structure, rather than a random pile of broken jars. The amphora shards were arranged in layers, with lime often sprinkled between them to neutralize the leftover oil and prevent foul odors from developing. Over time, this method formed the mound that exists today.

Amphorae without bases were filled with fragments and used to create artificial terraces. More shards were dumped behind these "amphora walls" until they reached the top. A new row would then be started slightly behind the previous one, forming a sloping hill that gradually increased in height until it reached its current size.

Monte Testaccio and its Connection to the Roman Economy

Monte Testaccio in Rome has been a subject of archaeological interest since the 19th century, with significant contributions from Heinrich Dressel, a German archaeologist. Dressel's pioneering work led to the documentation of thousands of amphora inscriptions, published in Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum XV,2.

The Dressel 20 Amphorae

The hill is an artificial mound composed of amphora fragments, situated in Rome’s ancient dock area. It served as a dumping ground, likely from the reign of Augustus until the era of Valerian and Gallienus, with the most recent inscriptions dating to A.D. 254-255.

The majority of the amphorae found are of the Dressel 20 type, originating from the province of Baetica (modern southern Spain). These amphorae were produced along the Guadalquivir River and its tributaries, particularly between Seville and Córdoba. Their average capacity ranged between 66 and 76 liters, with a rough, hard fabric that initially appeared buff-colored, later evolving to red with a white slip coating.

Dressel 20 amphorae are notable for their frequent stamps and painted inscriptions, which followed a standardized format, detailing the weight of the vessel, the quantity of olive oil it carried (measured in Roman pounds), and additional data in cursive script. ("The archaeological study of Monte Testaccio" by Pedro Paulo A. Funari)

Image #1: Dressel 20, Credits: The Society of Antiquaries of London

Image #2: Amphorae No.2, Dressel 20, Credits: Claude Valette, CC BY-ND 2.0

Image #3: Dressel 20 Side View, Credits: The Society of Antiquaries of London

The Origins of Monte Testaccio

Monte Testaccio, located just within Rome's Aurelian Walls in the south, has been the subject of various interpretations dating back to at least the 13th century. Its origins were speculated upon in numerous literary genres, including pilgrimage guides, humanist texts, and broader discussions of world history, eschatology, and geology.

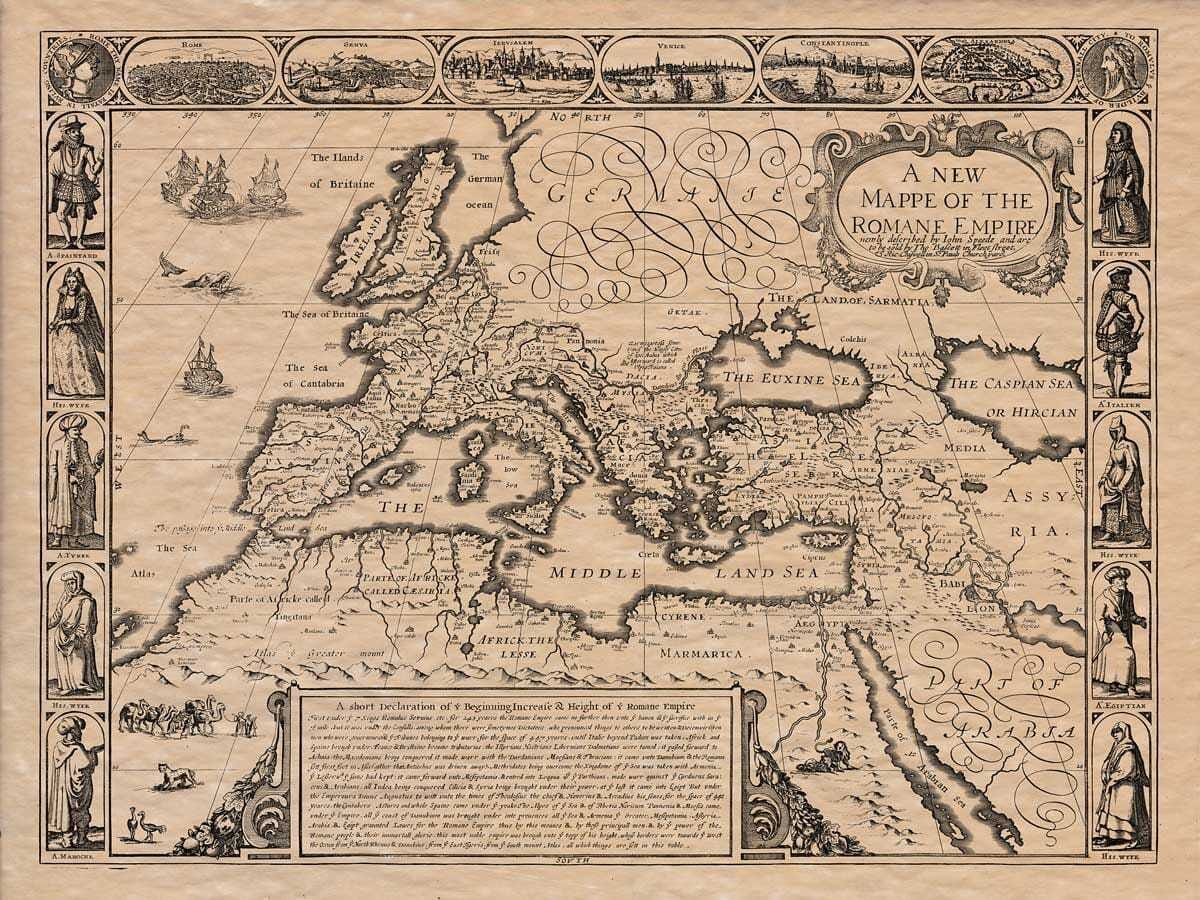

The most enduring explanation suggested that Monte Testaccio was formed from materials brought from across the Roman Empire, possibly earthenware or earth itself, as a form of symbolic or monetary tribute. This idea was often linked to the Mausoleum of Augustus, which was also believed to contain earth from all over the empire.

Other interpretations viewed the mound as being made from locally produced potsherds, either the waste from nearby potteries or material generated on-site. Modern scholarship, however, focuses on archaeological data to understand the mound's creation and its role in Roman production, consumption, and trade. In medieval and early modern times, the site was also associated with carnival games.

From at least the 13th century, texts referred to a man-made mound called "monte d'ogne terra" or "mons omnis terra," thought to contain earth brought from across the world.

This was interpreted as a symbol of Rome's global dominance.

Old Roman Empire Map, Credits: John Speed, The Old Map Company of Great Britain

While the precise location was sometimes unclear, this idea paralleled the description of the Mausoleum in the Mirabilia and was later applied to Monte Testaccio from the early 15th century. Current scholarship suggests that these associations with earthen or monetary tribute might have evolved from earlier traditions tied to the Mausoleum. Moreover, in some contexts, the symbolic significance of a man-made mound of tributary earth in Rome was seen as more important than its exact location.

The earliest mention of Monte Testaccio appears in La composizione del mondo (1282) by Ristoro d’Arezzo, a cosmological work. In a passage discussing man-made mountains, Ristoro explains that the Romans collected earth from across the world as tribute to symbolize their dominance, creating a hill known as the "monte d'ogne terra."

While Ristoro's discussion on mountains draws heavily from scholars like Avicenna, Albertus Magnus, and Vincent of Beauvais, none of them address man-made mountains specifically. This focus on artificial formations seems to be Ristoro's original contribution, reflecting his broader interest in human-made artifacts and classical works, which he often compared to craft processes.

Ristoro also provides another example of a man-made hill near Arezzo, which he likely knew firsthand. His observations have been linked to the Mausoleum of Augustus, as he references Emperor Augustus twice in the context of Roman global supremacy. However, by the late 15th century, his work was interpreted as describing Monte Testaccio.

By the early 15th century, the term "mons omnis terra" was indeed used for Monte Testaccio. One of the earliest recorded mentions comes from Adam Usk's Chronicle (1405), where he describes carnival games at Testaccio, calling it the "mountain of all earth" because it was made from soil brought from all over the world to symbolize universal lordship. Usk's description, possibly based on a city guidebook, is thought to reflect his personal observations of the games.

This association of Monte Testaccio with collected soil also appears in pilgrimage literature. John Capgrave's Solace of Pilgrimes (mid-15th century) describes the hill as being formed by pots of earth sent as tribute. He suggests a proportional relationship between the amount of soil and the size or distance of the contributing region, mirroring the contemporary practice of offering different indulgences based on how far pilgrims had traveled, with those from farther away receiving greater benefits. (Mons manufactus: Rome's man-made mountans between history and natural history, by Lucy Donkin)

Monte Testaccio and the Distribution of Olive Oil in Ancient Rome

Estudios sobre el Monte Testaccio (Roma) VI, is part of a series of studies under the Instrumenta collection, which focuses on various findings related to Monte Testaccio. This particular volume compiles research from the excavation campaigns of 2000 and 2005. It covers several topics, including the types of amphorae discovered, inscriptions, and detailed analyses of the stamps and markings on the amphorae. The research is heavily focused on understanding the distribution and origins of olive oil containers from regions like Baetica (southern Spain) and Africa.

The analysis of organic residues found in some amphorae from Monte Testaccio reveals that porous materials, such as ceramic amphorae, absorb the liquids with which they come into contact. This property has been widely studied since the mid-20th century to provide insights into the contents and uses of ancient ceramics.

Research by many scholars, demonstrated that amphorae could retain traces of substances like olive oil, wine, and other commodities transported in the Roman Empire. These analyses help identify the specific goods traded and stored in these amphorae, providing a clearer picture of the economic activities surrounding Monte Testaccio and the broader Roman trade network.

The study of the amphorae from Monte Testaccio, particularly those used in the olive oil trade between Baetica (modern Andalusia, Spain) and Rome, reveals significant insights into the geographic and economic networks of the Roman Empire. Most of the amphorae found at Monte Testaccio are of the Dressel 20 type, which was specifically designed for transporting olive oil. These amphorae (as already mentioned) were produced in the Guadalquivir Valley, Baetica, one of the most productive regions for olive oil in the Roman world.

The economic significance of this trade was profound. Olive oil was a staple commodity in the Roman Empire, used not only in cooking but also for lighting and various industrial processes. The transportation of Baetican olive oil to Rome exemplifies the vast logistical networks maintained by the empire to supply its capital with essential goods. The amphorae, stamped with identifying marks and often bearing inscriptions (tituli picti), provide detailed evidence about the organization of this trade, including the production centers, merchants, and the quantities of oil transported.

According to a researcher’s calculations, and with one million people living in Rome, this translates into six billion liters of olive oil that was transported over the course of Roman history.

These findings highlight the complexity of Roman trade, showing how local production in Baetica was integrated into an imperial system of distribution that spanned the Mediterranean. The movement of goods like olive oil was tightly controlled and required sophisticated logistical coordination, demonstrating the importance of economic centers like Baetica in sustaining the empire.

The Significance of Monte Testaccio

While a garbage dump may not have the allure of famous sites like the Forum or Colosseum, scholars are using Monte Testaccio to gain insights into the ancient Roman economy. Similar to how modern economies depend on crude oil, ancient Rome heavily relied on olive oil.

For over 250 years, starting from at least the first century A.D., large quantities of amphorae filled with olive oil were shipped from Roman provinces to the city, where they were unloaded, emptied, and discarded at Monte Testaccio. In the absence of extensive written records, these amphorae offer crucial evidence to answer important questions about the Roman economy—how it functioned, the level of control the emperor had, and whether certain sectors were state-supported or operated freely.

According to José Remesal, co-director of the Monte Testaccio excavations, the site contained around 25 million complete amphorae.

Dressel 20 Closeup, Credits: The Society of Antiquaries of London

During excavations, teams meticulously washed, sorted, and catalogued amphorae fragments, searching for stamped or painted names and numbers that could tell the story of each vessel. Although research at Monte Testaccio began in the late 19th century, it’s only in the past 30 years that scholars have fully recognized the amphorae's role in understanding the Roman imperial economy. One of the key challenges, as Remesal points out, is the lack of consecutive records, which makes Monte Testaccio a unique and valuable chronological record of Roman commerce.

For over 2,000 years, Monte Testaccio has stood largely undisturbed in the Emporium district, Rome's main port along the Tiber River from the late Republic to the fall of the empire in A.D. 476. The site was an active part of daily Roman life until the construction of a new city wall between A.D. 271 and 280 by emperors Aurelian and Probus, which cut off Monte Testaccio from the river and ended its function as a dump.

Monte Testaccio in Modern Times

After the fall of Rome, the area was mostly abandoned, though the hill continued to play a role in the city’s life. In the Middle Ages, it was used for religious festivals, and the surrounding area hosted jousting tournaments and public spectacles. In the 19th century, it was briefly used by Giuseppe Garibaldi as a gun emplacement during the fight for Italian unification.

Throughout history, Monte Testaccio served various purposes, from being a site for picnics to housing wine cellars, thanks to its naturally cool interior. However, in more recent times, it was closed to the public when it became associated with illicit activities.

For centuries, Monte Testaccio was thought to be a dumping ground for debris from the fire of A.D. 64 that devastated much of the city, or for discarded funerary urns. The amphora fragments were also used to make tiles for local repairs and taken as souvenirs by visitors. It wasn’t until 1872 that Heinrich Dressel started to classify the amphorae. (Archaeology magazine, March/April 2009, Article “Trash talk” by Jarett A. Lobell)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: